In a field teeming with visionaries and innovators, it is a challenge to narrow down a list of movers and shakers whom others emulate, admire, and follow to see where the specialty is heading. The 10 whom CRST has chosen to profile are a small but stellar group of talented ophthalmic surgeons who exemplify excellence. Some have been at it since reducing the number of radial keratotomy incisions from 16 to eight was hot news. Others were novices when lenticular procedures began encroaching on LASIK’s territory. Whether early or late in their careers, male or female, academicians or private practitioners, all share a desire to advance ophthalmic techniques and technology with an ultimate goal of improving outcomes.

Richard L. Lindstrom, MD

Just Say Yes

Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, has had his hand in almost every major development in modern anterior segment surgery as an academician, clinician, researcher, and product innovator, but at this stage of his career, the aspect of his professional life that he finds most gratifying is his relationship with his fellows. “I have about 80 fellows scattered across the United States and around the world,” he says. “Some of them are department chairs and are responsible for major contributions to ophthalmology themselves. As time goes by, one of the more meaningful things to me is thinking back to all of those fellows whom I’ve trained, seeing what they do, and continuing to interact with them.”

Dr. Lindstrom at age 18 in 1965 (top) and today.

Although he is often lauded for his well-known contributions to lenticular and laser surgery, one of Dr. Lindstrom’s innovations has more than stood the test of time, while flying under the radar. “One of my first products was Optisol-GS [Bausch & Lomb], which is still the most widely used corneal preservation medium,” he remarks. “It’s unlikely that people know that Optisol-GS was invented in my lab when I was at the University of Minnesota almost 30 years ago. Looking back, that one certainly had legs.”

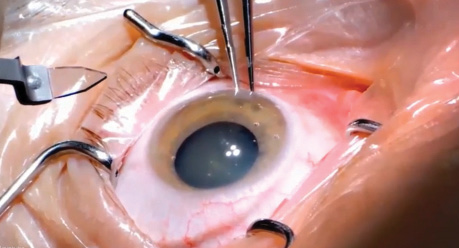

Watch it Now

Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, performs cataract surgery using intraoperative aberrometry in a post-LASIK patient.

Dr. Lindstrom did not have a lifelong vision of being a doctor. Instead, he says that he was, in a sense, chosen. He grew up thinking that he would go into the family’s construction business. When he was an undergraduate student, the dean of medicine was randomly assigned as his advisor, and that changed everything. “He was very charismatic, and he talked me into going into medicine,” Dr. Lindstrom recalls. “Then, when I was a first-year medical student, a new young professor in cornea, Don Doughman, MD, needed a student to work with him in the laboratory. After being recommended by the same dean of medicine, I ended up working in the Department of Ophthalmology and Cornea.” The rest, as they say, is history.

Dr. Lindstrom’s advice to others regarding finding their niche and living their passion? “Say yes to opportunity,” he urges. “It might be tempting to back away from the unknown, but just say yes. I was 32 years old and had never worked with industry when I was asked to be the chief medical officer of 3M Vision Care. Saying yes ended up earning me the equivalent of an on-the-job MBA. Among other things, I learned that industry is as committed to the best interest of their patients as I am to mine.”

Marguerite McDonald, MD

Refractive Royalty

About the only way Marguerite McDonald, MD, could have broken more ground in refractive surgery is if she had taken a jackhammer to it. If not for an incidental detour, however, refractive surgery might have been the road not taken. “In advance of my arrival, I had been assigned to be the corneal inflammation/uveitis fellow at Louisiana State University,” she remembers. “Meanwhile, as a third-year resident, I read … [a] landmark paper [by Herbert Kaufman, MD] about epikeratophakia and became so excited about refractive surgery that I called Dr. Kaufman and asked if I could be reassigned to the epikeratophakia project when I started my fellowship.”

Dr. McDonald performs surgery on one of the earliest PRK patients.

Eventually, Dr. McDonald went on to head the research team that investigated the use of the excimer laser for the correction of optical error, and she has racked up a list of firsts that permanently place her in the prestigious court of refractive royalty. Dr. McDonald performed the world’s first excimer laser treatment to eliminate or reduce the need for glasses and contact lenses; she performed the world’s first excimer laser surgeries for hyperopia; she performed the world’s first Summit/Autonomous wavefront-based excimer laser surgeries, which were also the first wavefront-based laser surgeries in the Americas; she was the first North American surgeon to perform epi-LASIK; and she was the first surgeon in the Americas to perform epi-Bowman keratectomy. In addition, Dr. McDonald was the first female president of both the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery and the International Society of Refractive Surgery.

None of these accomplishments would populate her curriculum vitae had she been afraid to go out on a limb. “It was a great risk to pursue the excimer project,” she says. “The original data were so bleak that my cornea fellow, my research coordinator, and my chief technician all left me at once. They basically told me that I was misguided and they couldn’t stand being associated any longer with such a ‘loser’ project.” Dr. McDonald looked past the negativity and took the advice that she recommends to others: “You only live once. Do what gives you joy. Don’t get to the end of your life with regrets about the professional path not taken.”

Developments in ophthalmology that excite Dr. McDonald today include a shorter pathway to approval than in the past, thanks to changes at the FDA. She also wants to acknowledge the invaluable involvement of her academic colleagues and corporate partners in her contributions to the specialty. “They must share the credit for these achievements,” she says, “because ultimately, it is always about the team.”

Vance Thompson, MD

Healthy Respect for Life Balance

Surgeons are often chided for their super-sized egos, but if Vance Thompson, MD, has even an average-sized ego, he clearly checked it at the clinic’s doorway before donning his first labcoat. Despite his pivotal role in the evolution of today’s most advanced refractive and cataract surgery developments, he likes to think he is most well known for being a caring person. “When my partners, coworkers, or comrades thank me for caring about them or for helping or advising them through a situation, that means a tremendous amount to me,” he says.

Watch it Now

Vance Thompson, MD, delivers the 2015 Sheets Martin Lecture entitled “Getting There: Thriving in Modern Day Medicine.

Dr. Thompson discusses the importance of the “work family” in a practice’s culture and patients’ experiences.

Dr. Thompson recalls that his interest in attending medical school was based on “a realization that one of the most impactful ways I could serve and influence my fellow human was through diagnosing, explaining, and, if necessary, treating their problem in a way that relieved their anxiety and brought them inner peace.” He expected to be a small-town family physician, but two milestones changed that plan. “The first was, as a junior in medical school, I spent time with an ophthalmologist and witnessed the impact of [his] surgically correcting vision on his patients. It made me have such a deep desire to be an eye surgeon that I worried about my joy in life if I did not achieve this goal,” Dr. Thompson explains. The second milestone came at the 1989 annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. “I attended a Visx-sponsored breakfast, along [with] my wife, where Marguerite McDonald, MD, explained how the excimer laser could safely and predictably change corneal shape and treat refractive error,” he recalls. “As we walked out, my wife said, ‘If I were you, I would learn about that laser. It’s going to make a huge difference in our world.’ It was a profound observation, and I passionately pursued a fellowship in refractive surgery.”

A fellowship in refractive and cataract surgery with Daniel Durrie, MD, and John Hunkeler, MD, imprinted his career. “They were both excimer laser investigators, and as the fellow helping to run the PRK and [phototherapeutic keratectomy] studies on partially sighted eyes and then sighted eyes, I was excited to continue with clinical research in my home state,” Dr. Thompson remarks. “That initiative was rewarded by a young CEO, David Muller, PhD, who believed in me as an excimer laser investigator even though it was the beginning of my career. That sequence of events set the stage for my research and technology development career, and I will forever be thankful for that.”

Dr. Thompson’s passion for what he does stays fresh, he says, because he has a healthy respect for life balance. “Take time to rest, and give attention to those around you who love you,” he advises.

Robert Maloney, MD

From Expert to Acolyte

Robert Maloney, MD, was one of the first eye surgeons to take the daring step of concentrating exclusively on refractive procedures. “The biggest obstacle that I faced early in my career was that refractive surgery was such a disrespected field,” Dr. Maloney comments. He recalls receiving feedback from a pathologist in response to an eye bank eye on which he had performed radial keratotomy. The pathology report stated, “Why anyone would think an operation like this should be done on humans is beyond me.” According to Dr. Maloney, this remark “helped me realize that the field was held in such low esteem that to be a respected refractive surgeon would require being very rigorous. That propelled me into doing careful, thoughtful research, with both small studies and clinical trials. This also led me to seek out a fellowship with George O. Waring III, MD, who was known as a prodigious thinker as well as the principal investigator of the PERK [Prospective Evaluation of Radial Keratotomy] study.” Dr. Maloney says, ultimately, that “nasty comment” defined the direction of his early career, which was all about lasers and LASIK. He says he would like to be remembered for describing the procedure’s complications and how to manage them.

From left to right, Osama Ibrahim Ahmed, MD, George O. Waring III, MD, and Dr. Maloney during their early excimer laser research at Emory University in Atlanta.

Dr. Maloney teaches Dr. Phillip Pastoral how to perform cataract surgery in the Marshall Islands in 1991.

In an interesting twist, Dr. Maloney would also like to be known as someone who contributed to bringing the Light Adjustable Lens (Calhoun Vision) to the world. In 2008, the surgeon who broke new ground by dedicating his practice to refractive surgery started to see that laser refractive surgery was at a standstill, whereas tremendous innovation was occurring in IOLs. Dr. Maloney decided he would either have to become a cataract surgeon or retire, and he was not ready for the latter. “I went from being an expert to being an acolyte,” he says. “I had to think like a student again. So many things had changed in 12 years. It was exciting. It turned out that, as much as I like teaching, I enjoy learning even more.”

In addition to breathing life into the second half of his career, cataract surgery provided Dr. Maloney with an opportunity to give a gift that keeps on giving. He and Antonio Capone, MD, travelled to the Marshall Islands for a weeklong visit to perform cataract surgery on needy patients. The ophthalmologists found a vast number of people blind from cataracts and realized that they had no hope of making a dent in the problem by themselves. They adjusted their plan so that one of them could continue performing surgery, while the other taught a local surgeon how to perform the procedure. Three years later, the local surgeon had essentially cured cataract blindness in the country. “That really makes me proud,” Dr. Maloney says. “It was the ultimate example of the saying, If you give a man a fish, he eats for a day. If you teach a man to fish, he eats for a lifetime.”

Audrey Talley Rostov, MD

Passion for Global Health

While in medical school, Audrey Talley Rostov, MD, knew she was attracted to surgery, but it was not until her rotation in ophthalmology that she narrowed the field and met her match. “I was really struck by the difference that eye surgery could make in peoples’ quality of life,” she remembers.

Dr. Talley Rostov with medical students from the National Institute of Medical Sciences medical college in Jaipur, India.

The issue of quality of life continues to motivate her as she immerses herself in global health initiatives, primarily with SightLife. “Being part of the mission to eliminate corneal blindness worldwide has been one of the most fulfilling parts of my practice,” says Dr. Talley Rostov, who travels to India several times a year to train surgeons in corneal transplant and cataract surgery. Meeting patients and hearing their stories gave her an appreciation of how profoundly vision loss affects not only them but also their families and even their community. “By helping restore their vision, we’re helping more than that one person,” says Dr. Talley Rostov. During her first trip to India, she visited a hospital where, she says, there was one corneal surgeon for millions of patients. “That was one of the things that helped me realize that I felt strongly about intensifying efforts for working in global health,” she states.

In between trips to India and work in the United States establishing surgeon-training curricula for SightLife, Dr. Talley Rostov is always looking for ways to improve corneal transplantation techniques. “In global health, I look at things from a perspective of how can we do this in a way that’s accessible for surgeons in India,” she explains. “On one hand, I’m all about making the most of what you have. For example, I’ll teach how to transplant a cornea with a simple instrument like a 30-gauge needle versus a high-tech device that might be prohibitively expensive. On the other hand, I’m excited about all of the technology that’s enabling us to optimize vision as opposed to simply restoring sight. It’s an interesting and exciting duality.”

Iqbal Ike K. Ahmed, MD

Respectful Rebel

Iqbal Ike K. Ahmed, MD, grew up feeling different because he was different. Born to South Asian parents in the middle of Canada’s Saskatchewan prairie, he remembers that the distinction was palpable. Rather than be oppressed by it, he used this sense of otherness as a positive vehicle. “It drove me to realize that I don’t need the shackles of tradition to lock me into a certain way of doing things; I can explore different ways of doing things better,” he says.

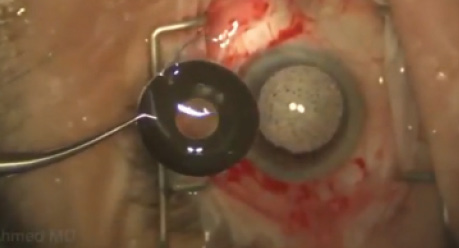

Watch it Now

Iqbal Ike K. Ahmed, MD, demonstrates sutureless fixation of a customized iris prosthesis and IOL.

That is exactly what Dr. Ahmed did with the introduction of microinvasive glaucoma surgery, a term he coined. “I decided to pursue a glaucoma fellowship, because I thought it was an area that was ripe for innovation,” he states. “I wanted to shake things up a bit.” Dr. Ahmed has far exceeded that goal. “I’ve been fortunate to be involved in developing most of the new devices in glaucoma surgical intervention and drug delivery today, which are two very exciting areas in glaucoma therapy [that] didn’t exist just a few years ago,” he continues.

Although much of his motivation comes from a desire to revamp established paradigms, he maintains respect for the people whose constructs he aims to improve. “I grew up in a household that respects seniority and authority, and I firmly believe in being kind, in being appropriate, and in not making anyone feel bad through this process,” says Dr. Ahmed, who lauds veteran glaucoma specialist Alan Crandall, MD, with whom he did his glaucoma fellowship. “I give a lot of credit to him for what I’ve been able to accomplish,” Dr. Ahmed remarks.

Along with his contributions to the field of interventional glaucoma surgery, Dr. Ahmed is known for his surgical skill and is called on to handle challenging cases around the globe. “I’m always surrounded by learners, whether they’re medical students, residents, fellows, or colleagues, and I love teaching. It helps me develop ideas; it makes me better. I always tell my residents and fellows and students, ‘Play to your strength; it’s okay to be different. In fact, it can actually be an asset.’” Clearly still comfortable wearing the cloak of distinction that being different offered him as a youth, Dr. Ahmed says, “I prefer to be on the outside looking in, because I feel that provides the best vantage point.”

Richard M. Awdeh, MD

Intersection of High Tech and Health Care

Richard M. Awdeh, MD, says he may be found at “the intersection of tech and health care, … [because it] is a really exciting and cool place to work.”

Since early in his career, he has wanted to work in an academic environment that supported research and product development. “I wanted to be able to do things that I thought could actually come out of the lab and out of the clinic to help people,” he explains. Dr. Awdeh is an idea man, however, whose creative proclivity cannot be contained in a conventional environment. In addition to practicing surgery and contributing to research and product development at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, he is the founder of CheckedUp, a mobile health care platform focused on strengthening doctor-patient communication. He is also the founder of Cirle, a medical technology incubator poised to launch a surgical navigation system that, in Dr. Awdeh’s estimation, will be a game changer. The system, called Spectrus (to be marketed by Bausch + Lomb), is designed to allow the easy digital transfer of data from the clinic to the OR.

“The simplest comparison is to a smartphone,” he explains. “Ten years ago, none of us could imagine why we’d need one. Today, we can’t live without them. I came up with the idea for the surgical navigation system when I was in the OR. I’d look into the microscope and wonder, why is there no digital guidance? Why don’t I have access to the patient images and file? Why was my drive to work more high tech than what I’m doing in the OR?”

Dr. Awdeh says he has encountered helpful, supportive, encouraging people along the way as well as those who recommended he plant his feet on solid ground and take a safer path. He cut out the naysayers without looking back. Now, he peoples his company with young thinkers who can benefit from supportive mentoring. “My expectation is that they’ll each experience their own a-ha moments and that, 10 years from now, they’ll all be doing great things, whether for us or on their own.”

William F. Wiley, MD

From Vacation to Vocation

From an early age, William F. Wiley, MD, was involved in the world of ophthalmic innovation. His father, Robert Wiley, MD, along with a colleague inadvertently started an annual ophthalmic surgery meeting when the two took their families on a tropical vacation and then spent an inordinate amount of time talking shop. “The next year, they invited a third colleague and, the following year, a fourth, and that eventually turned into the Caribbean Eye Meeting,” recalls Dr. Wiley. “I must have gone to 10 of those meetings while I was growing up. That was my spring break.” Listening to eye surgeons discuss their work and seeing them present outcomes on pioneering techniques and technology influenced his passion for research and innovation, as did his brainstorming sessions with his dad.

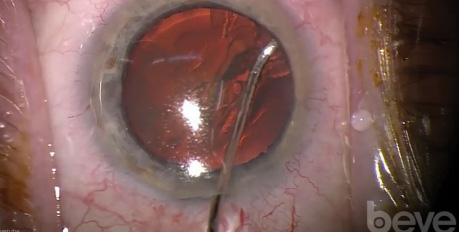

Watch it Now

William F. Wiley, MD, presents an instrument he designed to cleave cortex off the capsule in laser cataract surgery.

“I remember sitting in the kitchen with my dad when he talked about how we needed a lens that could be adjusted once it was in the eye, and he would invite my input,” recollects Dr. Wiley. “He developed an idea for a variable-focus IOL, and I remember feeling like I had a real role in helping him with that. He had several versions of the patent, but eventually, he let the patents expire, because it became too expensive to hold them. Many years later, those patents were regenerated in a way that is similar to the Light Adjustable Lens, and my practice is one of the largest clinical trial investigators for that lens. It’s really exciting to see that come full circle from the spark of the light bulb idea in my kitchen to being part of a clinical trial 25 years later.”

Dr. Wiley briefly considered the fields of orthopedics or dermatology. When it was time to make a decision, it is not surprising that he stepped into the ophthalmic ring and then, not only took over his father’s practice, but also expanded it into several satellite facilities and opened a research arm of the practice to fully invest time and resources into product innovation. Today, he is known for his ability to finesse a product from the early-idea stage through the innovation cycle to when it is ready for widespread clinical use. Dr. Wiley says, “I think that’s where my strengths are: taking something that’s in its early development, working through the early challenges, and finding solutions.”

Gary Wörtz, MD

Wunderkind Pushes the Envelope

With less than a decade of active practice under his belt, Gary Wörtz, MD, is a bit of a wunderkind, having earned the attention of those whose business it is to track ophthalmic innovators. He was drawn to surgery in medical school but felt disenchanted and unsure of his path until he spent a day observing cataract surgery. “From that moment, I was hooked,” he says.

Dr. Wörtz took the bootstrap approach to landing his first gig by starting a solo practice in rural Kentucky straight out of residency. He says the experience humbled him in ways that perhaps no other venture could. “Unless you have started a practice or a business, you’ll never fully appreciate all the things that everyone in your office does to make it work,” he explains.

LISTEN UP

Gary Wörtz, MD, is the host of a new podcast, “Ophthalmology off the Grid,” which provides an honest assessment of controversial topics in the field.

About halfway through the practice’s 8-year lifespan, Dr. Wörtz had a vision of an IOL unlike any that preceded it. “Every IOL essentially looks and functions the same, so they all tend to have the same advantages and disadvantages,” he remarks. “I took sort of a Steve Jobs approach by stepping outside of the paradigm and thinking differently about IOLs, and this idea just popped into my mind,” he recalls and says that development of the novel IOL has been eagerly supported by private investors. “It’s really been an amazing journey to take an idea and turn it into something that is tangible,” continues Dr. Wörtz, who anticipates having “compelling” human data later this year.

In his relatively new role at Commonwealth Eye Surgery, a high-volume group practice in Lexington, Kentucky, Dr. Wörtz draws clinical inspiration from the ophthalmic giants upon whose shoulders he stands such as James Gills, MD, Charles Kelman, MD, and his mentor and partner Lance Ferguson, MD. For personal inspiration, he looks to his church and its guiding principles. “Religion is often misunderstood and misapplied, but I find that you can’t go wrong by applying the Golden Rule in almost any situation,” he says.

Stephen Slade, MD

Never Too Old to Ask for Advice

Stephen Slade, MD, hopes that he will be remembered for helping to develop and then integrating and teaching new technologies, given his lengthy list of ophthalmic surgery triumphs. They include performing the first LASIK procedure and the first Crystalens (Bausch + Lomb) implantation in the United States as well as the first femtosecond laser LASIK flap and the first laser cataract procedure in this country. That said, Dr. Slade wants his legacy to be focused on patients. “I think I’ve managed to develop a good reputation among my patients here in Texas, and the main thing that I’d like to be remembered for is that I did my best for my patients,” he says.

This surgeon took bold steps in his career when moving from a large group practice to academics and then to a solo private practice, and he has been involved in a healthy number of startup ventures. According to Dr. Slade, however, he takes the greatest risk every time he steps into the OR: “As good as the technology is and as good as we’ve become at using it, I think we take risks every day operating on people. Patients are risking their sight with us. Every day, 15, 20, 30 people are trusting us to cut open their eye. I think about that every day, and it’s still really phenomenal to me.”

Dr. Slade can rattle off a long list of peers who have helped and inspired him throughout his career starting with Herbert Kaufman MD, Douglas Koch, MD, the late Lee Nordan, MD, and Steven Brint, MD. They and many others gave him their time and expertise as he shifted some of his attention from LASIK to cataract surgery, as trends dictated. “I’ve been surprised that you’re never too old to go to people and ask for advice and have them be eager to provide help,” he remarks. “There are people who are teachers and people who are not, and if you find ones who are, they’re invaluable.”

He cites other important lessons: “It’s better to listen than it is to talk, it’s better to think than to worry, and patients first!”

Rochelle Nataloni

• freelance medical writer with 25 years’ experience specializing in eye care, aesthetics, and practice management

• (856) 401-8859; rochellemedwriter@gmail.com; Twitter @JustRochelleN; www.linkedin.com/in/rochellenataloni