Our lives as ophthalmologists are generally fulfilling, and our profession is uniquely placed to keep us happy because our specialty is about perpetual renewal; we are in charge of preserving and repairing the most precious sense: vision.

However, at times, our discipline lacks a truly artistic dimension. The visual arts—painting, drawing, and of course, photography—exploit the medium of vision to relay an emotion. It is this emotional dimension that I seek through my regular (but amateur) practice of photography. The primary goal of the visual sense is to immediately inform us about the surrounding world and guide us within it. But when this sense is expressed as a vector of emotion or pleasure that can be shared, another fascinating goal is achieved.

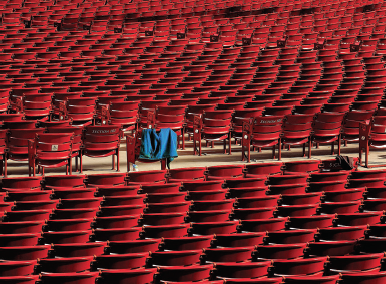

I enjoy photography for exactly this quality—the enjoyment it gives to me and possibly to those who see my photos. I do not necessarily think I have a particular style, other than to capture the essence of something or to offer a different perspective from what the human observer simply perceives. For example, I like to capture something that is normally purely informative and transform it into something a bit more thought-provoking. I enjoy when I observe something that should be unremarkable (or perhaps even unnoticed) and can appreciate it for its iconographic quality. It does not have to be sophisticated.

When you take photographs, you must first visualize the photo in your mind. The best result is when the final snapshot is exactly what the photographer envisioned before he or she even took the picture. I like to capture small human silhouettes in some of my landscapes or indoor photographs because it triggers a reflective interaction with the observer and raises questions about our place in the world. Conventions or exhibition halls offer excellent opportunities to capture such photos, where colleagues often wander through vast and architecturally interesting spaces.

Beyond the art, the technical aspects of photography are interesting to an ophthalmologist who is interested in ocular optics. From a cognitive point of view, it is fascinating to understand how our subjective visual appreciation is more sensitive to certain compositions or arrangements of colors and contrasts. It is a complex subject because there are many subjective parameters.

We often talk about visual quality in refractive or cataract surgery, but what is the quality of what is seen? What essentially defines a beautiful image? These are quite challenging questions and certainly difficult to quantify, unlike the parameters we use to express the quality of vision such as contrast sensitivity thresholds. Despite cultural and educational differences, I believe that artistic photography can arouse the interest of observers through universal mechanisms, and these principles are often taught in introductory works in photography and the visual arts in general. Geometry is a descriptive basis for any image, and I often try to provide some clear geometrical structure in my photographs.

The use of smartphones and social media has profoundly changed our relationship to photography, which we now consume constantly. Some tags such as #nofilter, now popular on social media platforms, would suggest that there is an absolute unfiltered visual truth. This ignores the fact that vision is a process—a process that can be explained as placing a series of filters on light captured by the eye, before the final image is appreciated at the level of the occipital lobes. On the contrary, these filters make it possible to free oneself of this subjectivity and to recognize images for what they are: perceptual illusions.