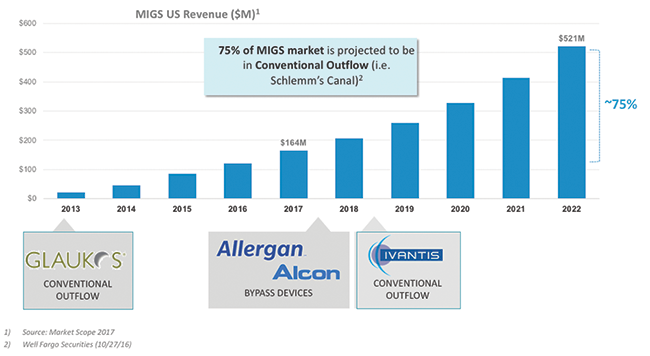

Among all of the different glaucoma procedures, the minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) category is showing the fastest growth (Figure 1). This is, undoubtedly, owing to the safety of MIGS as well as device implantation in conjunction with cataract surgery. We are pleased to have an expert panel of both cataract and glaucoma surgeons to discuss their experiences with MIGS in general and with the Hydrus Microstent (Ivantis), in particular.

—David F. Chang, MD, moderator

Figure 1. MIGS is a large and rapidly growing market opportunity.

MIGS Overview

David F. Chang, MD: From a cataract surgeon’s perspective, Dr. McCabe, how does MIGS fit into your practice?

Cathleen M. McCabe, MD: As a busy cataract refractive surgeon, I believe it is important to offer my patients a complete and comprehensive evaluation and treatment plan. Over the last decade, cataract surgeons have learned that we cannot ignore a patient’s astigmatism. Today, we cannot ignore the fact that patients with glaucoma need lower IOPs. If I can address all of my patients’ problems—remove their cataracts; treat their refractive needs, including astigmatism and possibly presbyopia; and also impact their glaucoma—in the same setting, that is a real benefit to them. MIGS fits in perfectly with that mentality of treating as many ocular problems possible in the safest and least invasive way at the time of surgery.

Jason J. Jones, MD: I completely agree. I have seen patients who were able to stop or significantly reduce their use of IOP-lowering drops after MIGS. It is like a new lease on life for them, with less worry and more freedom in terms of their daily activities. Using antiglaucoma drops every day reinforces the negative aspect of what their eye pressure is doing. With MIGS, we can safely relieve that burden in a way that enhances the whole experience.

William F. Wiley, MD: We have incorporated MIGS into our cataract surgeries for some time, and it has been a great addition to our practice.

We do a fair amount of comanagement, and the first month after cataract surgery in a patient with glaucoma was always a little rocky. Ultimately, we knew the surgery would lower the pressure, but during the perioperative period, we were concerned about pressure spikes, particularly in a comanaged scenario. With MIGS, we can lower the perioperative pressure, making the postoperative period easier and more stress-free for the optometrist, and allowing both of us to sleep better at night.

Dr. Chang: Has the fact that you offer MIGS had an impact on your cataract patient referrals?

Dr. Wiley: Our referring partners are recognizing that cataract surgeons who perform MIGS are delivering an additional benefit for their patients. We find that MIGS has helped grow our practice. The referral patterns are showing that it is meaningful and good for patients and patient care.

Dr. McCabe: I am also concerned about the condition of the ocular surface and its impact on quality of vision in patients who receive premium IOLs. Ocular surface disease is the biggest impediment to a patient’s satisfaction with his or her visual outcome. If I can help patients eliminate their IOP-lowering drops, with their concomitant toxicity to the ocular surface, that is another huge advantage in meeting patients’ expectations.

Dr. Chang: That is a good point. Earlier, you mentioned that cataract surgeons cannot ignore astigmatism, and we know that about 36% of our cataract patients will have 1.00 D or more of astigmatism.1 Do we have any data on the number of patients in a cataract practice who have mild to moderate glaucoma and would be candidates for a MIGS procedure?

Dr. McCabe: About 20% of our patients have open-angle glaucoma, and about 80% of those patients are probably in the mild to moderate category. That is a large number of patients. The burden of need in our population is great.

Dr. Chang: Dr. Harasymowycz, as a glaucoma specialist, you manage the entire spectrum of glaucoma severity. Where does MIGS fit in with your treatment paradigm?

Paul Harasymowycz, MD: MIGS enables us to offer safer alternatives to traditional glaucoma surgeries. Most often, when we operate on eyes with moderate glaucoma, we are aiming for lower IOPs. We have noted from recent trials, however, that despite having pressures in the higher teens, glaucoma often continues to progress.2 Not only does MIGS enable us to bridge the gap before going straight to filtration procedures, we can offer patients a safer alternative to lower the pressure and reduce their medications at the same time. For a chronic disease like glaucoma, which affects the ocular surface, every additional drop that a patient uses may impede the success of future filtration surgeries. Therefore, it is important to decrease them, if possible. In addition, compliance is a huge issue in our glaucoma population. If we can reduce the number of drops patients need, for example, from 3 per day to 1 per day, that is a significant win.

Thomas W. Samuelson, MD: The MIGS evolution has been incredibly liberating for glaucoma specialists to better mitigate risk in glaucoma surgery. In the mid-90s to early 2000s, our treatment options ranged from medicine and laser, which are safe but only modestly effective, to trabeculectomy, which is effective but marginally safe. That differential in risk is quite a leap.

Coupling phacoemulsification, which is an effective pressure-lowering procedure, with a safe procedure within the MIGS category to augment that effect, has dramatically reduced the number of patients who need to be subjected to the more aggressive surgeries. While I still perform trabeculectomies and implant tubes because of disease severity, the percentage is nowhere near what it used to be. To have these safer options has been game-changing.

Dr. Chang: Where are we in terms of MIGS adoption? Do we have any statistics regarding current trends?

Dr. McCabe: According to the 2016 survey by the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS), only 30% of respondents have actively adopted MIGS.3 That leaves a large population of surgeons who are still on the sidelines. Maybe they do not feel comfortable working in the angle or they are unsure of the technology and the data that support it. About one-third of surgeons are interested and considering MIGS.

Dr. Samuelson: I believe those statistics are exactly correct, but my guess is they are skewed, because the ASCRS membership in general tends to be comprised of early adopters to new technologies.

In the population of ophthalmologists at large, I believe the penetration is somewhat less, partly because there is some skepticism. Patients did not achieve pressures of 10 mm Hg in the iStent Trabecular Micro-Bypass Stent (Glaukos) trial,4,5 but the reality is, most patients with glaucoma do not need pressures of 10 mm Hg or 8 mm Hg or 6 mm Hg, and the risk to achieve such low pressures is unacceptable for the majority of glaucoma patients. I believe the ophthalmology community is taking notice that MIGS is here to stay, and now a higher percentage of surgeons are starting to investigate their options. While the penetration has been low, I think it will begin to ramp up fast now.

Dr. Wiley: I second that. I think there were two hurdles to adoption. First, surgeons were not sure the results were compelling, and they used that as an excuse to stay on the sidelines. Second, there are some technical challenges. We are working in a new space, the angle, and I think some surgeons were not comfortable doing that. They were looking at the risk versus the reward and asking, “Is learning this new skill going to be worthwhile? How much pressure-lowering are we really going to see?”

When those questions were answered satisfactorily and the hurdles were overcome, many surgeons began performing MIGS on every patient who is a good candidate.

The conversion rate for patients is high when they understand the benefits of MIGS in combination with cataract surgery. That is an easy sell. The only stumbling block is when we encounter insurance carriers that are not on board. Most payers, including Medicare and the large insurance companies, have approved it.

Dr. McCabe: You make a good point about acceptance by patients. As cataract surgeons, we have a great deal of information to share with our patients, starting with an explanation of what a cataract is. We are concerned that offering MIGS will take even more chair time. I have found exactly what you describe, Dr. Wiley, that explaining MIGS procedures takes very little additional chair time. Patients understand that they have a problem, and typically they are already using an IOP-lowering medication. If we say that we can help them better control their pressure or that they may even be able to stop using a medication, only a short conversation is necessary for patients to understand that this would be a benefit for them.

Dr. Samuelson: Regarding chair time, I agree that the conversation is brief when discussing such a safe procedure. When we suggest more aggressive treatment options that can have perioperative surprises or delayed visual recovery, however, we must inform patients in advance about those possibilities.

Stenting the canal is a great opportunity because we can look a patient in the eye and say, “I have an option for you that had no differences in safety or visual recovery than cataract surgery alone in the FDA trials.” As soon as patients hear they are statistically more likely to need less medication or be medication-free, and their visual recovery will be the same with no increase in complications, they say, “Sure. Sign me up.” That’s a brief and straightforward conversation to have with a patient. When we get more aggressive with our operations, however, the conversation gets more involved, and we have to tell patients, “Well, your vision might be blurry for a while, because your pressure might be transiently too low, or there might be some bleeding and some time needed for the blood to clear postoperatively.” That discussion increases chair time. When we talk to patients first about what a cataract is, second, about their IOL and refractive options, and third, what we do for glaucoma, it does consume chair time. When stenting the canal is an option, it is a quick discussion.

MIGS Learning Curve: Tips and Pearls

Dr. Chang: Let us discuss the learning curve for MIGS and the technical challenges of intraoperative gonioscopy. What advice would you offer surgeons who are just beginning to perform this surgery?

Dr. McCabe: I recommend first becoming comfortable visualizing the angle during surgery. Disposable gonioprisms are now available, so that a surgeon does not have to invest in a gonioprism to start learning the skills needed to be successful with MIGS. At the end of a routine cataract case, you can turn the patient’s head away from you, turn your microscope toward you, fill the anterior chamber adequately with viscoelastic, put viscoelastic on the surface of the cornea, and get comfortable looking at the angle structures, understanding where Schlemm’s canal and the trabecular meshwork are located. You can then take an instrument such as a Sinskey hook (Katena) and hold it where you would hold a device that you will put into the trabecular meshwork or Schlemm’s canal. Practicing these maneuvers will help you feel comfortable before you start your first MIGS case.

Dr. Jones: Practice really pays off when you start operating on your first cases, not only for yourself but also for your staff. It helps lay the groundwork for success. Visualization is the key, and the newer gonioprisms make this much easier to do.

Many great videos are available to familiarize surgeons with the technique. Wet labs are also valuable in that they enable surgeons to practice this surgery in a safe environment, stop and ask questions, or reassess what they are doing and how they will place the device.

Dr. Harasymowycz: I agree that visualization is key. When using the first generation of iStent, I think targeting is important, and learning beforehand in wet labs and getting comfortable in the space is crucial. I have seen fantastic cataract surgeons start with little practice and not be comfortable with the currently approved MIGS technology. Thankfully, newer technologies and improvements will make insertion more comfortable.

Dr. Samuelson: Over the years at different courses and symposia, I have seen many videos of surgeons performing MIGS. Usually, if a surgeon is struggling, the view is also poor. I cannot recall seeing a video where the view is perfect and the surgeon was fumbling around. I believe there is a direct correlation between maintaining a good view, seeing what you are doing, and performing good MIGS surgery.

General Opinions of MIGS Efficacy

Dr. Chang: Many cataract surgeons look to glaucoma specialists to get their take on the efficacy of any new treatment approach. Dr. Harasymowycz, how does the glaucoma subspecialty community view MIGS?

Dr. Harasymowycz: In terms of efficacy with the current approved trabecular micro-bypass stent, there are data that show the more of them you implant, the lower the IOP.6 That definitely improves efficacy. If you select your patients properly, you will get better efficacy. A patient who has extremely high pressures is probably not the best candidate. In my opinion, patients who are undergoing cataract surgery and whose pressures are well-controlled with multiple medications should be the first patients to whom you offer MIGS. They will have better outcomes in terms of medication reduction.

Dr. Chang: We have heard that some cataract surgeons are performing MIGS, but many are not. Dr. Samuelson, in your opinion, are most glaucoma subspecialists performing MIGS now?

Dr. Samuelson: I believe the percentage of glaucoma specialists performing MIGS is increasing after some initial skepticism. Our definition of success over the years has skewed us toward procedures that have unacceptable safety profiles for mild to moderate disease. The majority of patients worldwide who have glaucoma have mild to moderate disease. Often when I lecture at glaucoma conferences, audience members say they do not see mild or moderate disease; they see only severe disease. I challenge that, frankly, because it is uncommon that glaucoma progresses symmetrically in each eye. Most of the time, if the disease in one eye is severe, the disease in the other eye is moderate. When treating the eye with moderate disease, we must make sure that we are not subjecting it to more risk than the disease itself. I think all surgeons who manage patients with glaucoma need to have a MIGS option, a safer option, to offer their patients. They may still perform trabeculectomies and tubes, but they also need to have a safe option to offer.

Treatments and Indications

Dr. Chang: Let us discuss specific MIGS options. We have supraciliary, canal, and subconjunctival microstents, and we also have phacoemulsification alone. What indications direct you toward a particular procedure? Dr. McCabe, let’s first discuss patients who have cataracts?

Dr. McCabe: If my patient has a cataract and is considering surgery, and if he or she has mild or moderate open-angle glaucoma and is using 1 or 2 medications, I look at the options available to treat the glaucoma at the same time. Every patient who has open-angle glaucoma and needs cataract surgery has the option to have a MIGS device implanted at the time of surgery.

Dr. Jones: As I review patients’ charts or EMR, I look at the cataract-related issues, primarily vision, but I also want to know their pressures, if they use antiglaucoma drops, and if they have a history of glaucoma. Then I prepare the sequence of my discussion with each patient. Basically, it is a given that for patients who have any issues related to the burden of open-angle glaucoma, I will offer them MIGS. In general, it is an easy uptake for this procedure, because patients do not enjoy using drops all of the time. This is something we can do to help them in an easy and efficient manner.

Dr. Chang: Once you have determined the need to perform MIGS, how do you decide whether to use a subconjunctival, a supraciliary, or a canal microstent? What factors guide your decision-making?

Dr. McCabe: My primary consideration always is safety. I look at the safest procedure to achieve the result that I need to best take care of my patient’s medical problem. With that in mind, trabecular meshwork bypass stents, in my experience, are number one in safety for MIGS procedures. Then I have to decide if the device I can use in that space will provide the pressure-lowering effect that I want to achieve.

Dr. Harasymowycz: If the glaucoma is not well-controlled and pressures are extremely high, then perhaps we should consider not using the trabecular pathway, because we are already proving that the conventional outflow system is not working. In those cases, I am likely to choose a subconjunctival or a supraciliary microstent. If the patient’s conjunctiva is scarred and has had years of exposure to antiglaucoma drops, and if the patient has a beefy red eye, a subconjunctival filtration procedure is not likely to be successful. Sometimes we do not have the luxury of time to pretreat the conjunctiva with topical steroids to decrease the inflammation. Then, even though the pressures may be slightly uncontrolled, I would still perform a trabecular bypass procedure or supraciliary in that case.

Dr. Samuelson: There is no set algorithm. Several factors must be considered. Disease severity is important, but it does not completely rule the day. For example, if my patient has severe disease that has been well-controlled and stable for 10 years, I do not want to subject him or her to more risk than necessary. In such patients, I might perform a canal procedure. On the other hand, if my patient has mild disease but a pressure of 45 mm Hg while using 4 drops, I have to be more aggressive; technically, the disease is mild because there is minimal damage, but the risk is high. To summarize, I consider several factors, including severity of disease, a patient’s ability to use and tolerate medications, and, importantly, the likelihood of progression. The patient I just mentioned might have an early nasal step but with an IOP of 45 mm Hg, the likelihood of progression is extremely high, and I need to be more aggressive. Those two factors—disease stage and likelihood of progression—are not always exactly correlated. Likelihood of progression may apply to a patient with mild disease.

Dr. McCabe: That is true, particularly if a patient has severe disease in the other eye or if you have detected progression in the other eye. That is another consideration, looking at the whole patient and not only at that specific eye.

Dr. Harasymowycz: I want to reiterate Dr. Samuelson’s point about disease severity. Just because a patient has more advanced disease does not mean the canal will not function. In fact, I find canal stenting even safer in more advanced disease if it has been well-controlled. Thus far, I have seen no evidence and, in my personal practice, I find that even though patients have had glaucoma for many years, but have been stable with advanced disease, we still have successful outcomes. That pathway is still a viable alternative.

Dr. Samuelson: Dr. Harasymowycz is hitting on something important that our payers need to understand. If a patient has been hanging by a thread for 10 years and is stable, we want to be gentle with that patient and not necessarily subject him or her to something that could threaten the remaining fixation. That patient might benefit from a safer MIGS procedure. Our perioperative management will change. We might see the patient for a same-day pressure check. We might see the patient more frequently. We will monitor the patient more carefully for a steroid response. But patients should have the option of choosing a safer procedure, regardless of their disease stage. Likelihood of progression is an important variable. A patient whose pressures have been stable for 10 years may be less likely to progress than someone with mild disease.

Dr. Chang: Dr. McCabe mentioned that she feels the meshwork and canal-based procedures have the most favorable safety profiles. Do others share that opinion? Are there data on that?

Dr. Jones: There are definitely data to support that opinion.4,5,7 If we look at comparable devices in the supraciliary space to trabecular bypass, short-term and long-term complications exist. I have had some personal experience with those, having participated in some of the trials. That experience helped guide me toward deciding where I want to go with most of my patients. Safety is not just a catchphrase. This is a real-world, on-the-street issue that we must address, because we will be caring for these patients, and they will be living with the issue for a long time. Paying attention to safety is paramount.

Dr. Samuelson: It is worth emphasizing that the IDE/PMA iStent trial demonstrated no difference in safety and visual recovery in the phaco arm versus the phaco/iStent arm, and the soon-to-be-published Hydrus HORIZON trial had comparable safety data, as well.8 The CyPass Micro-Stent (Alcon) safety was better than I expected it to be, but if you look at it carefully, it is not quite as safe as the canal microstent.7 It has some other advantages. For example, perioperative pressure spike mitigation is terrific with CyPass. You do not see high pressures in the first couple of weeks as you sometimes do with canal surgery, and there seems to be far less steroid response. Even so, from a safety standpoint, I think the canal is still the safest route.

Dr. Chang: Glaucoma specialists will see some pseudophakic patients whose IOPs are not well-controlled and who need full-thickness filtering surgery. Do you have a preference regarding what MIGS procedure might have been previously employed?

Dr. Harasymowycz: It is clear that if the canal has been tried as the first glaucoma procedure and the conjunctiva is not scarred, further glaucoma filtering procedures will definitely have better outcomes than if they had been previously operated subconjunctivally.

Dr. Samuelson: It is advantageous when a referring surgeon leaves the conjunctiva and the sclera untouched. I think some of our early attempts at safer, alternative surgical glaucoma procedures violated too much prime conjunctival/scleral territory. For example, canaloplasty from an ab externo approach was safer than trabeculectomy—I did it a fair amount in the late 1990s—but we violated vast amounts of conjunctiva. With a variety of procedures we can now perform canaloplasty ab interno, sparing the conjunctiva and the sclera, and the same would apply for the supraciliary space. If you can leave the conjunctiva and sclera untouched for future use if needed, it is a huge advantage.

Dr. Harasymowycz: You had also specified that we are talking about stenting the canal. Many procedures require that we remove trabecular meshwork tissue. Whenever we lower IOP in a second surgery and have a large open cleft, we are more likely to see a hyphema postoperatively. Whereas, if a stent has been implanted, there is less bleeding in the second surgery.

Dr. McCabe: We are talking about stents through the trabecular meshwork, in Schlemm’s canal, as though that is just one category, but we can affect that space in a couple of different ways. We have talked about dilating it, as with canaloplasty ab interno, but we can dilate it using other methods. I am really excited about the Hydrus Microstent, because that is one of its features. Aside from providing access to the space through the trabecular meshwork, it stents and stretches that space for a greater amount of real estate—90°, 3 clock hours. That is a significant improvement on what we have currently.

Focus on Hydrus

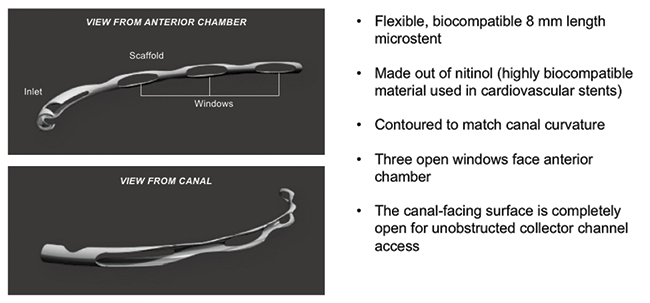

Dr. Chang: Dr. Samuelson, please provide some background on the Hydrus Microstent (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Roughly the size of an eyelash, the Hydrus Microstent is a next-generation MIGS device designed to reduce eye pressure by reestablishing flow through Schlemm’s canal, the eye’s natural outflow pathway.

Dr. Samuelson: I remember this device long before it was called the Hydrus Microstent, long before there was a company called Ivantis. Denali Medical was part of the very active med-tech community in Minneapolis. Surgeon Steven J. Grosser, MD, and I were working with the company in the basement of the Phillips Eye Institute to develop a microstent for MIGS. At that time, it was a two-operator system. The surgeon held the needle in the canal and an assistant deployed it. It quickly became apparent that it needed to be a one-surgeon process, and it evolved into the current clinically viable product. Denali Medical then hired a CEO, spun off a new company named Ivantis, and moved to Orange County, where the device and the company have come to fruition.

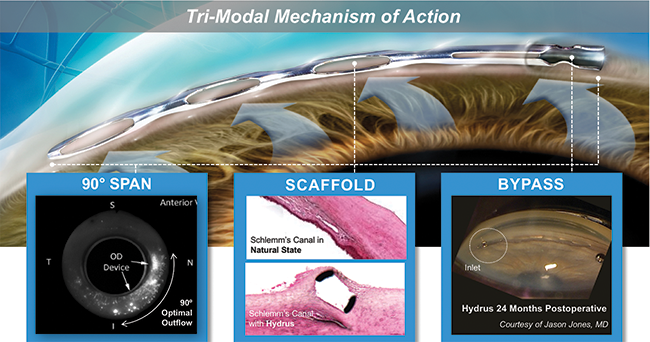

Chief among the advantages of Hydrus Microstent is safety, as it is implanted in Schlemm’s canal and enjoys the inherent safety in this space. It is 8 mm long, so it occupies a full quadrant of the canal. As an aside, if we were to dissect an eye and place Schlemm’s canal longitudinally on a table, it would measure about 36 mm. Because the Hydrus Microstent occupies almost a full one-fourth of the canal space, we are more likely to communicate with a collector channel in that 8 mm segment, which is a great advantage. The Hydrus Microstent has a trimodal mechanism of action, bypassing the trabecular meshwork, dilating the canal, and scaffolding it open (Figure 3). Data from the HORIZON trial support that those features add efficacy while maintaining the safety typical of the canal.8

Figure 3. The Hydrus Microstent has a Trimodal mechanism of action: (1) It creates a bypass through the trabecular meshwork, allowing outflow of aqueous humor; (2) it then dilates and scaffolds Schlemm canal to augment outflow; and (3) its length spans 90° of the canal to provide consistent access to the fluid collector channels of the eye.

Dr. McCabe: One of the nice aspects of the Hydrus Microstent is that you can target placement, and, ergonomically, it is much easier to reach the part of the canal that has the most collector channels, the nasal quadrant.

Dr. Chang: Dr. Samuelson, if there are nearly 36 mm of total length to Schlemm’s canal, what is the length of an iStent?

Dr. Samuelson: An iStent is 1 mm long, so targeted placement becomes important. I select areas of blood reflux or increased pigment. Of course, you need to go where it is ergonomically acceptable or within your primary cataract incision, although there is no harm in making a secondary incision, if needed. The greatest density of collector channels is in the inferonasal quadrant, so I usually go there. Targeted placement is important with the first-generation of iStent. The iStent Inject (Glaukos) has two preloaded stents, so we can select multiple spots. This is less important with the Hydrus Microstent, because it has an 8 mm expanse.

Dr. Jones: Another advantage of the Hydrus Microstent relates to the scaffolding and dilation of Schlemm’s canal. The Hydrus Microstent actually scaffolds it open. Unlike viscoelastic that will dissipate eventually, the scaffolding will keep Schlemm’s canal dilated.

The ease of placement of the Hydrus Microstent makes this device much more user-friendly than one might expect. It looks like a large device that must go in a very small space. The reality is that you end up cannulating Schlemm’s canal with the device so you know it’s in the canal. You visualize the entire implantation process. It is comfortable for patients, so they are not moving. They don’t feel it like they would with a supraciliary device. The surgeon can feel the resistance, or lack thereof, and can sense that the device is going into the proper location. This is unlike other devices that are sharper and are placed in the tissue and stay there. With them, you may wonder, “Did I get it in the right place? Did I actually hit my target?” The Hydrus Microstent enables surgeons to work in this space and have confidence they will place it properly. All of these factors make this a kinder, gentler approach to trabecular bypass, but with the other advantages of additional actions, such as scaffolding and dilation. All of those factors create a scenario for success that will be welcome in our space.

Dr. Wiley: You bring up a great point as far as knowing you are in the right spot. We talked about the trimodal effect of the Hydrus Microstent, but there is one other effect: that of being in the right spot. If a stent is not placed correctly, the probability of reducing the pressure is low. A stent is either in the right spot or it is not. With the Hydrus Microstent, you can see it, and you can be confident you have placed it correctly. Simply by placing it in the correct area, we ensure its effectiveness.

Dr. McCabe: It is reassuring for surgeons to know where the stents are after placement. You could place many stents in the wrong place and have a bad perception of the efficacy of MIGS devices in general. Being able to visualize all of those windows as the device goes through Schlemm’s canal improves our level of confidence.

I participated in the Hydrus Microstent study, so I have had the opportunity of seeing some of my patients more than 2 years after implantation.8 The device looks beautiful in place and does not move. You can feel confident that it is doing what it is supposed to do. I describe this as an elegant procedure.

Dr. Samuelson: I love it! Glaucoma surgery is elegant. That is absolutely true. I could not make that statement 10 years ago.

A point that Dr. McCabe just made is worth emphasizing. I was a surgeon in the original iStent trial, and my first cases are in the trial.4,5 The surgeons who participated in the trial were novices at implanting a microstent within Schlemm’s canal, and I can promise you, the device was probably not in the canal in many of the patients in the trial. Despite that limitation, however, the device was efficacious enough to be approved.

What is interesting about the Hydrus Microstent and maybe why the numbers are so good in the HORIZON trial, is that almost by definition, the device is in the canal in every patient.8 It would be obvious if it was not in the canal, and you would not leave it in the eye if it was not in the canal. The Hydrus has an advantage because you can visibly verify placement in the canal. It could not be anywhere else and look the way it does postoperatively. In the HORIZON trial, close to 100% of the patients enrolled have the device in the canal.8 I doubt we can say that in the iStent trial, because we were all novice surgeons and verification is more challenging.

Dr. McCabe: The advantage is that everyone who implants a Hydrus Microstent will have immediate feedback that they have done the right thing and placed it in the right space. They will not have to wait to see if it is efficacious or not and wonder if a lack of efficacy is related to imperfect placement.

Dr. Samuelson: Originally, I thought that might be a disadvantage of the device. The first iteration was almost twice as long, but then it was reduced to 8 mm, and as discussed earlier, it is obvious to everyone in the room if it goes in the canal or not. In the US trial, 97% of deployments were successful.9

Dr. McCabe: I have had the opportunity to use the Hydrus Microstent in less-than-ideal circumstances during mission trips outside the United States where visualization was not optimal because the equipment was antiquated and the patients were unable to cooperate fully. In those circumstances, even surgeons who had little experience with the device found it easy to implant. I am reluctant to use the word “easy,” but it is a relatively short learning curve, and there is good confirmation that you have placed the device where you need it to be, even when visualization is not ideal.

Hydrus Microstent Learning Curve

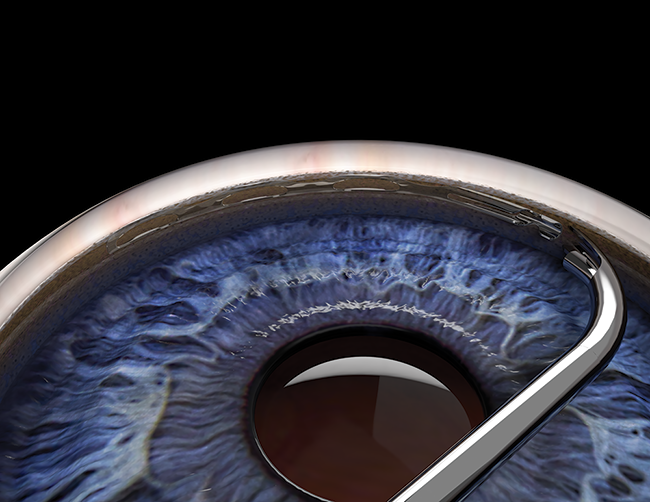

Dr. Chang: When people initially see how large a Hydrus Microstent is, it looks rather intimidating. With any new MIGS procedure, there is a certain amount of performance anxiety. We wonder, “Will I actually succeed in implanting this device after I have told the patient that we need to do this?”

So let us address the learning curve for the Hydrus Microstent and also share pearls for implanting it.

Dr. Wiley: Initially, I was impressed by the size of the Hydrus Microstent and thought it might be challenging to place, but I like to use the analogy of a capsular tension ring. A capsular tension ring is a functionally huge device, about 24 mm, but we do not think twice about its size. It is cannulated into the bag, and we insert it. Similarly, with the Hydrus Microstent, you cannulate Schlemm’s canal and then advance it, and you can always reverse it if you need to pull it out (Figure 4). By contrast, an iStent is small, and once you let go, it is difficult to retrieve or manipulate. The initial step with a Hydrus Microstent is cannulating Schlemm’s canal. Once that is done, it is easily advanced.

Figure 4. The Hydrus Microstent is advanced until the device has fully scaffolded Schlemm canal 90°.

Dr. McCabe: You make a good point. The real action is incising trabecular meshwork and starting to advance the stent. After that, you slowly slide the device into Schlemm’s canal. The action of the surgeon is minimal: Make the incision, hold the inserter at the correct angle, and advance the implant.

Dr. Jones: My experience was somewhat different from those of the other panelists. I started with a supraciliary device in the CyPass study,7 then I went to Hydrus Microstent, and then to iStent. I found the iStent was the most difficult of these devices in terms of ensuring proper placement. What was helpful for me was that I knew how to visualize in that space. If you are an iStent surgeon already, you are comfortable looking in the angle, so your transition to the Hydrus Microstent should be easy. I think that is a helpful experience to have in your background. If you have not had much experience, Ivantis’ wet lab preparation is quite helpful and confidence-inspiring. Basically, taking human donor limbal rim tissue and implanting multiple devices over and over again helps to make this an easy transition.

Dr. Harasymowycz: In the wet lab, it is important with any device to try to reload it, in case you have to do that during a surgery. You don’t want to start practicing reloading in a patient’s eye.

Dr. Jones: That is a good point.

Dr. McCabe: Like Dr. Jones, I also implanted a Hydrus Microstent before I implanted an iStent. I think that experience made it easier for me to know the anatomy, because with the Hydrus Microstent I had confirmation of exactly where that space is.

Dr. Harasymowycz: I believe surgeons will find placement of the second generation of iStent, the iStent Inject, easier, but the confidence of knowing exactly where you are seems to be better with the Hydrus Microstent, because the iStent Inject is smaller, about 0.4 mm long, and in patients with deeper canals, it can go deep.

Dr. Samuelson: I would encourage surgeons to become thoroughly familiar with each individual device’s handpiece. Whether it is Xen45 (Allergan), CyPass, Hydrus Microstent, the Kahook Dual Blade (New World Medical), or iStent, know the device, know where to place your finger, know the deployment. A wet lab is a great learning environment.

In terms of tracking in the canal, the Hydrus is made of nitinol, an alloy of nickel and titanium, which is MRI-compatible up to 3 Tesla. It finds its place and glides in the canal smoothly. It has memory and is an advantageous material to work with.

Dr. McCabe: The two key preparations for implanting any MIGS device are visualization and becoming comfortable with the inserter, because different products do deploy differently. Sometimes I have to remind myself that with one device, I need to push down but with a different device, I should pull back. They are all somewhat different, and it is good to have that familiarity, that ergonomic feel, so that you are not thinking about it. It should be intuitive.

Dr. Samuelson: Exactly. I recall having to decide if I should advance the roller in one big motion or just inch it forward. I decided to inch it forward. You do not want to be making that decision during your first case. Knowing your deployment strategy preoperatively is important.

Dr. Chang: For people who are just getting started with MIGS, a key part of the learning curve will involve gonioscopy and surgical visualization. All of us probably learned a variety of little tricks for whichever MIGS device we used first. Familiarity with any MIGS device should make it much easier to adapt to another MIGS procedure.

Dr. Jones: In terms of visualization, the newest disposable gonioscopy device is basically a silicone lens that is placed on viscoelastic. This idea came from Ivantis and some of their development work. It is a nice device to use, because compression on the cornea is reduced, preserving visualization to its highest degree. The view is excellent, because you are using a pristine lens. I would strongly recommend those devices for surgeons who are just going into this area and even for surgeons who have already started but have difficulty with visualization.

Dr. Harasymowycz: In cataract surgery, sometimes we do our paracentesis a little farther peripherally. If you nick even small vessels, your visualization will not be as good, so I advise going a little more anteriorly in your first few cases to make sure there is no blood. It will make visualization easier.

Trial Data and Clinical Experience

Dr. Chang: Let us review the design and some of the key findings from the HORIZON trial.8

Dr. Harasymowycz: The HORIZON trial compares the efficacy of the Hydrus Microstent plus cataract surgery versus cataract surgery alone in mild to moderate glaucoma. This is a prospective, multicenter, single-masked, controlled, trial with 2 to 1 randomization. We looked at outcomes in terms of IOP-lowering and the number of antiglaucoma medications required at 1 and 2 years. An advantage of this trial is that it is a washout trial, so that the effect of medications is not there. It was interesting to see that even at 2 years, cataract surgery still lowers IOP. Over time, however, adding the stent lowers IOP further and decreases the burden of using medications.

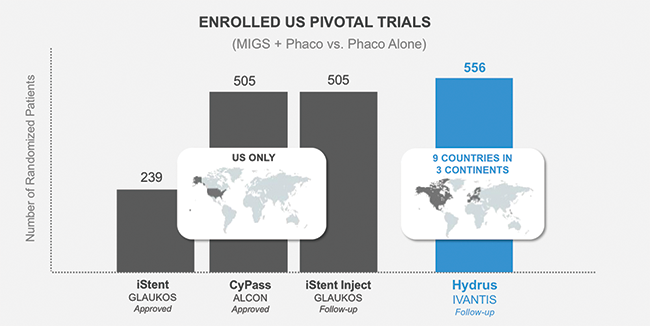

Dr. McCabe: Two exciting features of this trial were that it was global, unlike all of the other MIGS trials, and it was the largest MIGS trial to date, with 556 patients enrolled (Figure 5). That is an impressive number.

Figure 5. HORIZON is the largest ever MIGS pivotal trial.8

Dr. Chang: I appreciate that this trial provides 2-year data. Dr. McCabe, would you comment on the efficacy over the 2 years in the HORIZON trial?

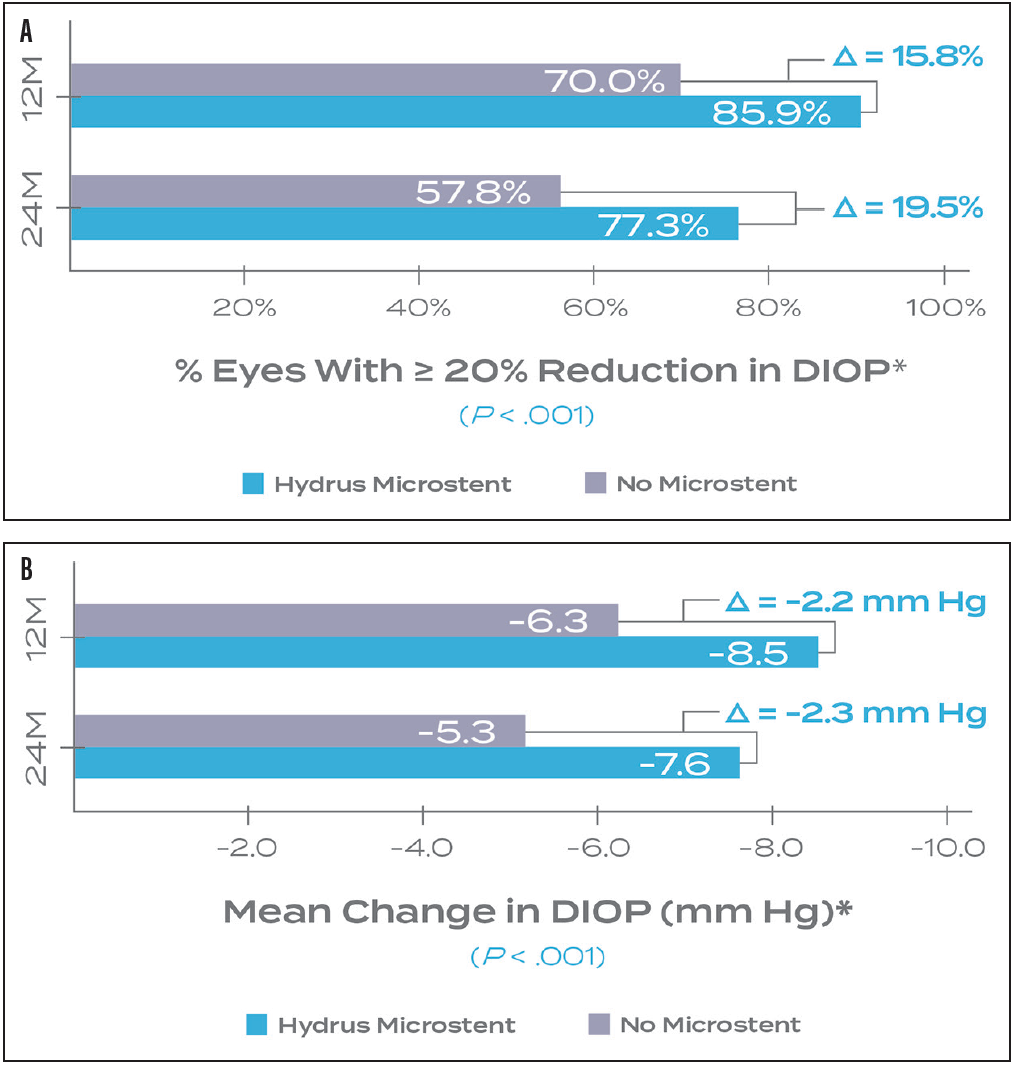

Dr. McCabe: Unlike other MIGS data that showed either stability or a decline over 2 years, the HORIZON trial demonstrated an increase in comparative effectiveness versus phaco alone over 2 years in both the 20% reduction primary endpoint and the unmedicated diurnal pressures (Figure 6).8 Seeing relative improvement over time rather than a decline is exciting.

Figure 6. The primary (A) and secondary (B) endpoints of the HORIZON Pivotal trial both demonstrated an increased treatment effect from 1 to 2 years.8

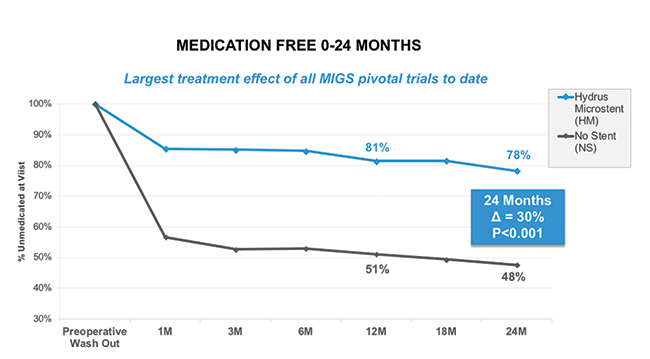

Dr. Jones: In the study, IOPs of participants who were medication-free decreased early and then remained low throughout the 2-year time frame (Figure 7). That is another positive result in terms of durability.

Figure 7. HORIZON: Medication Free.8

Dr. Chang: We discussed how difficult it can be to judge efficacy as a surgeon, particularly with the first devices implanted. Dr. Wiley, what has been your clinical experience with the Hydrus Microstent thus far?

Dr. Wiley: I had the opportunity to implant four or five Hydrus Microstents in Costa Rica. At the day 1 postoperative visit, every one of those patients had pressures lower than 15 mm Hg. These were patients who had significant pathology and glaucoma. Day 1 pressures that low were quite impressive. It was exciting to see that kind of immediate impact.

The online tracking that Ivantis developed for data collection and studying is quite beneficial. We can track results per surgeon, and we can track patients who underwent surgery elsewhere to see if low pressures are being maintained over time. I can still track those patients who had surgery with me in Costa Rica and see how they are doing.

Dr. McCabe: Ivantis has been proactive in taking the real-world data from patients globally who have had a Hydrus Microstent implanted and entering it into the Spectrum registry so that they can be monitored. As we know, study designs are inflexible, but once the devices are available, surgeons must decide who the appropriate patients are, when to implant the device, and what the postoperative care will be. These data represent a wide variety of real-world experiences in all comers, all glaucoma types. Just looking at those data and seeing what is happening in the real world is a powerful tool to teach us how to use this new technology in our own practices.

Dr. Jones: When using this device in patients in my practice during the study, I found that the effect was immediate. Patients did not have a hypotonous period, which may happen with some supraciliary devices, and consequently, they did not need to recover from hypotony or experience the pressure spikes we have seen in some patients. The transition into the postoperative period is smooth. In addition, with an immediate effect, you can tell patients with confidence, “We will not have to continue that medication for several weeks or months. We will see the effect of this device early on.” Not only is it an easy transition for patients, but it also facilitates adoption by surgeons and acceptance by referring doctors.

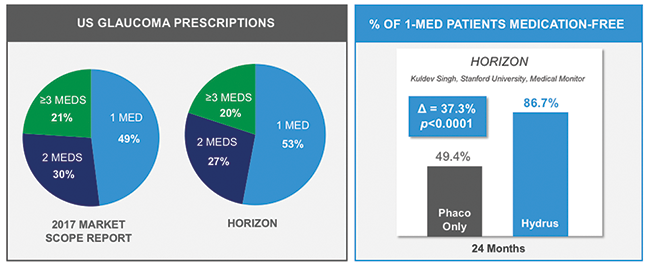

Dr. Samuelson: A procedure that can produce almost an 8 mm Hg IOP reduction at 2 years while correcting refractive error and reducing the need for antiglaucoma medications is an exciting option (Figure 8). There are many benefits associated with MIGS combined with cataract surgery. Now we have an elegant glaucoma option to pair with our elegant cataract option.

Figure 8. HORIZON: Over 86% of Hydrus Microstent patients on 1 medication were medication free compared to control at 2 years.8

Comparative Trials

Dr. Chang: Having a variety of MIGS devices from which to choose is beneficial for all cataract and glaucoma surgeons, but it does create a dilemma. How will we decide which is better for our patients? What clinical data will be available to help us make that decision?

Dr. Chang: Lacking direct head-to-head comparisons, we do have the FDA trials for each MIGS device in which they are compared to phaco alone as a control.5,7,8 Are these FDA clinical trials comparable? Can we use them to assess relative efficacy?

Dr. Jones: When we compare results from the COMPASS trial with those from the HORIZON trial, we see fairly similar outcomes in terms of pressure reduction. In terms of adverse events, however, a much higher percentage of patients needed more interventions in the COMPASS trial.7,8

Although we are comparing data from two different studies, the patients enrolled were similar in terms of demographics and their glaucoma status, and they all had cataract surgery. Therefore, I think there is some validity in comparing some of these issues. I believe we can say the HORIZON trial has a nice safety profile and perhaps a better one in comparison to similar trials, for example, the COMPASS study.

Dr. McCabe: Cataract surgeons have access to many different premium IOLs, enabling us to tailor treatments to our individual patients’ needs, with consideration of our experience and any potential side effects. Similarly, we will have many different MIGS options from which to choose. This is where the art of medicine comes into play. Our understanding of the risk/benefit profiles in our hands with our patients and our experience will dictate how we utilize these devices.

Conclusion

Dr. Chang: This has been an excellent discussion. We all agree that the future of MIGS is even brighter now that we have multiple different devices available to us. This greater diversity is not just in the surgical procedures themselves, but also in the outflow pathway that is utilized. These early studies are encouraging, particularly with respect to safety, and we look forward to more head-to-head and longer-term efficacy data.

1. Hoffmann PC, Hutz WW. Analysis of biometry and prevalence data for corneal astigmatism in 23,239 eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:1479-1485.

2. Harasymowycz P, Birt C, Gooi P, et al. Medical management of glaucoma in the 21st century from a Canadian perspective. J Ophthalmol. 2016;6509809. Epub 2016 Nov 8.

3. ASCRS Clinical Survey. Eyeworld. 2016. http://supplements.eyeworld.org/h/i/289602006-ascrs-clinical-survey-2016. Accessed December 28, 2017.

4. Samuelson TW, Katz LJ, Wells JM, et al; US iStent Study Group. Randomized evaluation of the trabecular micro-bypass stent with phacoemulsification in patients with glaucoma and cataract. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:459-467.

5. Craven ER, Katz LJ, Wells JM, Giamporcaro JE; iStent Study Group. Cataract surgery with trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation in patients with mild-to-moderate open-angle glaucoma and cataract: two-year follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1339-1345.

6. Belovay GW, Naqi A, Chan BJ, et al. Using multiple trabecular micro-bypass stents in cataract patients to treat open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1911-1917.

7. Vold S, Ahmed I, Craven ER, et al; CyPass Study Group. Two-year COMPASS trial results: supraciliary microstenting with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma and cataracts. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2103-2112.

8. Harasymowycz PJ. Canal stenting: Into Schlemm’s and beyond. Data presented at: American Academy of Ophthalmology Subspecialty Days; November 10-11, 2017; New Orleans, LA.

9. Hays CL, Gulati V, Fan S, et al. Improvement in outflow facility by two novel microinvasive glaucoma surgery implants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1893-1900.