Someone once said: “The future is built on the past.” To discuss present trends and future directions in phakic IOLs, it seems important to look back. When I completed my fellowship with the legendary Daniel S. Durrie, MD, in 1998, LASIK was the dominant refractive procedure. Phakic IOLs were still undergoing FDA trials, but I observed that the international experience with phakic IOLs indicated that they had a place in refractive surgery. At the time, we could see that high myopes had increased risk of glare and halos after LASIK, plus more risk of dry eyes.

When the iris-claw phakic IOL (Ophtec), designed by Jan G.F. Worst, MD (often called the Worst Phakic IOL in those early days—probably not the best name for a lens), received FDA approval, I began implanting it immediately to provide better quality of vision for high myopes. In the United States, the lens was renamed the Verisyse (Allergan, now Johnson & Johnson Vision) and in Europe the Artisan (Ophtec). Despite the astigmatism management needed because of the requisite large incision for this one-piece PMMA iris-fixated lens, for high myopes the Verisyse provided improved quality of vision and reduced the risk of halos compared with LASIK.

STAAR Surgical then received FDA approval for its foldable Implantable Contact Lens, later renamed the Visian ICL. I began implanting the lens at that time, and I conducted a matched-group study comparing the Verisyse to the Visian ICL. In those results, presented at the AAO and later published,1 we found better BCVA, UCVA, and accuracy within ±0.50 D with the Visian ICL. The Visian ICL then became my preferred lens.

SMOOTHING THE PROCESS

The mechanics of performing phakic IOL implantation were not patient-friendly in those days—each eye on different days, performed in an ambulatory surgery center (ASC), with painful laser peripheral iridotomy (PI) performed 1 to 2 weeks beforehand. I was determined to make the Visian ICL patient experience similar to that for LASIK but without compromising safety. I knew that would help the lens become more successful and more widely accepted by patients.

To accomplish this, I established the same Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) safety and sterility criteria used in ASCs in my office procedure room. I did this without becoming AAAHC certified, but rather working with the American Board of Eye Surgeons to use the AAAHC criteria for certification of my office phakic IOL procedure room.

The laser PI performed 1 to 2 weeks beforehand was painful and inconvenient for patients, and their vision was blurred for that procedure day. Therefore, I began incorporating the vacuum surgical PI technique described by the brilliant Kenneth J. Hoffer, MD.2 That meant there was no need for the laser PI performed weeks beforehand; I did the surgical PI at the time of the Visian ICL implantation. I also began implanting same-day bilateral Visian ICLs, one right after the other and using our excimer laser microscope for the procedures. With these changes, the Visian ICL experience was virtually the same as the LASIK experience for patients.

READY FOR PRIME TIME

In 2008, I was asked to perform Visian ICL surgery on one of my patients, sports journalist Alan Abrahamson, live on NBC’s Today Show during prime time. I performed bilateral Visian ICLs in my office procedure room under the LadarVision excimer laser (Alcon; no longer available).

The general public had largely never heard of nor seen a phakic IOL until that airing (Figure). This brought a tsunami of exposure and stirred a lot of interest. Surgeons around the country were getting calls about the Visian ICL.

Figure. In 2008, Dr. Boxer Wachler performed live Visian ICL surgery on NBC’s Today Show under the LadarVision excimer laser.

Afterward, I spoke at the Aspen Invitational Refractive Symposium about my bilateral, office-based Visian ICL protocol. The room was full of fellow high-volume LASIK surgeons, most of whom were reluctant at the time to do such a thing. STAAR Surgical then contracted me to develop the ICL Growth Program, a 10-part webinar training program for Visian ICL–trained surgeons, to teach them how to do bilateral, office-based, surgical PI Visian ICL implantation. The company recognized the need to make it a consumer-friendly procedure. I am happy to see more surgeons now performing bilateral phakic IOL implantation with surgical PIs. More surgeons are continuing to move phakic IOLs from their ASCs to their office procedure rooms, but at this stage there really should be many more surgeons doing it this way. There is a concurrent trend of moving cataract surgery from the ASC to office-based procedure rooms.

In September, Dr. Durrie became chairman of the board of iOR Partners (iorpartners.com), a company that specializes in moving IOL surgery from the ASC to an office-based location as part of the surgeon’s practice. This new venture will provide surgeons with a turnkey solution, offering a full suite of services including financial support, staff training, administration, product supply, and support services.

AN IMPORTANT ROLE

Now 11 years after Dr. Baikoff’s article in CRST (see accompanying excerpt below), phakic IOLs are clearly not a flash-in-the-pan phenomenon, like some other procedures we have seen come and go. Phakic IOLs are an important part of our mission to provide the best vision with the least side effects to people who want freedom from glasses and contact lenses.

Refractive Phakic IOLs of Then and Now

Herein, I share the development of and experience with these implants.

By Georges Baikoff, MD

In the 1950s, José Ignacio Barraquer, MD, of Spain; Benedetto Strampelli, MD, of Italy; M. Dannheim, MD, of Germany; and D. Peter Choyce, MD, FRCOphth, of London—the pioneers of intraocular implants—conducted the first trials using anterior chamber refractive lenses to correct high myopia in phakic eyes. Unfortunately, the initial experiments revealed unacceptable complication rates due to imperfections in IOL design.1 Glaucoma, corneal dystrophy, and hyphema were commonly observed, and anterior chamber implants—particularly refractive phakic implants—acquired a bad reputation.

EARLY PROTOTYPES

It was not until the mid-1980s that Svyatoslav N. Fyodorov, MD, of Moscow; Paul U. Fechner, MD, of Germany; and I resumed developing phakic implants.

Dr. Fyodorov began experimenting with a collar-button, pupil-fixated posterior chamber implant that ultimately led to the development of the Implantable Contact Lens (ICL; STAAR Surgical), the Adatomed implant (Chiron Adatomed), and the Phakic Refractive Lens (PRL; Ciba Vision). Dr. Fechner designed the Worst iris claw implant (Ophtec) and adapted it to correct high myopia. Later, Ophtec modified the implant to also correct hyperopia and astigmatism. I imagined an angle-supported implant to correct myopia similar to that designed by Charles D. Kelman, MD, of New York.

Over the last decade, the development of phakic implants has been erratic: first one type met with success, then another. In fact, the progress of these lenses was largely hindered by the importance of concurrent investment and research into corneal surgery, microkeratomes, and the excimer laser. Because LASIK developed so rapidly, today, its advantages and limitations are much better known. Due to the procedure’s drawbacks, interest and research in refractive implants are once again gaining momentum.

ADVANTAGES OF REFRACTIVE IMPLANTS

Apart from progressive myopia and cataract development, the stability of refractive results has been confirmed regardless of the implant type. Safety and efficacy ratios are superior to those obtained with LASIK, and optical aberrations are fewer.2,3 In most instances of high ametropia, the effective optical zone is larger, and the rate of nighttime halos is lower with refractive implantation versus corneal surgery. Additionally, fewer optical defects occur with industrial lens implantation compared with corneal surgery, because the ultimate shape of the corneal tissue depends on the individual’s healing ability. In most cases, refractive implant procedures are reversible. In the event of a sizing or power error, the lenses can be exchanged.

DISADVANTAGES OF REFRACTIVE IMPLANTS

The disadvantages of refractive implants depend on the lens model and its anatomical situation. Each new modification can induce an unexpected iatrogenous complication.

Angle-supported anterior chamber implants. Respecting a safety profile has eliminated the early endothelial trauma observed with the first models. To prevent endothelial loss, there must be a minimum of 1.5 mm between the edges of the optic and the endothelium. More than 80% of the first-generation (years, 1988–1989) ZB-type Baikoff phakic IOL implants have been extracted. Since 1990, and until last year, no known or published corneal dystrophy epidemic has been reported with new-generation implants.

Indeed, sudden drops in endothelial cells have been described in France, when the Vivarte (Figure 1) or Newlife lens (both manufactured by Carl Zeiss/IOLTech) was implanted in patients 4 or 5 years ago. During the first 3 or 4 years, the endothelial cell loss is physiological. A sudden drop in the number of endothelial cells occurred after the fourth year and led to explantations in 10% to 20% of cases. These implants were withdrawn from the market and a warning issued—not only with regard to these implants, but to all types of anterior chamber implants.

In our experience, we have noted that second-generation PMMA implants (ZB5M [Domilens] or Nuvita [Bausch & Lomb]) presented few endothelial problems, and the average number of years before it was explanted (for whatever reason) was approximately 11 years. It was only 2 years with the Vivarte and Newlife. We were unable to find anatomical reasoning for the endothelial cell loss. Moreover, there did not seem to be any relationship between the anterior chamber depth and endothelial cell loss. We, therefore, wondered if it was a question of hydrophilic polymer tolerance in the anterior chamber.

The future of angle-supported implants lies in perfecting the preoperative evaluation of the anterior chamber’s internal diameter. Anterior chamber implants have followed the example of posterior chamber implants and may now be inserted through a 3-mm or smaller self-sealing incision.

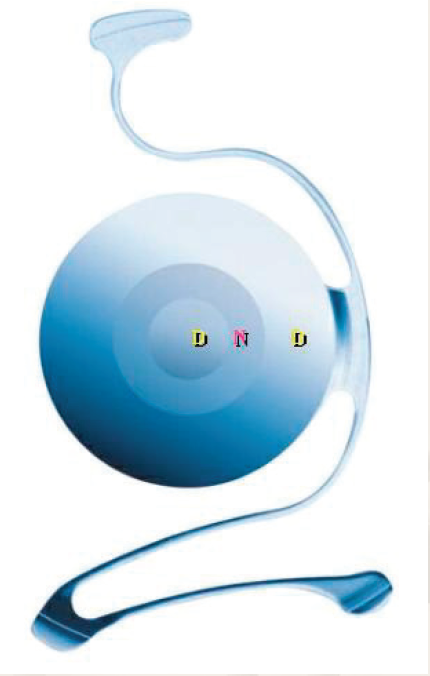

Iris claw/iris-fixated implants. The complication rate of iris-fixated phakic IOLs has fallen. Endothelial cell loss is acceptable, and inflammation, pupillary blocks, and IOL displacements are rare. A few implant dislocations were observed when the IOL was not firmly fixed at the iris.2,3 Pigment dispersion has been noted in hyperopes,2,3 and I observed several cases—essentially in hyperopes and in one case in a myope—when I carried out a retrospective analysis of the anterior chamber on several hundred patients using the Visante OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec). We were able to show that pigment dispersion always occurred when the crystalline lens rise was equal to or greater than 600 µm.1-6 The forward protrusion of the crystalline lens pushes the iris toward the front, creating a sandwich effect where the iris is squashed between the implant and the crystalline lens. At that moment, pigment dispersion syndrome occurs.

Therefore, we no longer offer iris-claw implants to patients if their crystalline lens height/rise is more than 300 µm. By keeping to this rule, we have been able to eradicate this problem from our practice. It is important to note, however, that the crystalline lens’ anterior pole moves forward by 20 µm per year. From 10 to 15 years on, we will once again be confronted with this problem.

To solve the large incision problem, a foldable version of the Artisan lens (Ophtec; marketed in the US as the Verisyse IOL by Advanced Medical Optics), called the Artiflex implant, is being developed.

Posterior chamber implants. Currently, surgeons prefer either the ICL or the PRL. The risk of cataract formation is still a problem, especially regarding the ICL. The rate increases with age and insufficient vaulting of the implant.4 Additionally, cases of unexplained intravitreous dislocations with the PRL have been recently published (oral communication with Dimitri Dementiev, MD, at the ESCRS Winter Meeting, Barcelona, Spain, February 2004). Whether this complication is due to surgical trauma, the cutting effect of the PRL’s edges or a fragile zonule is unknown. This complication has not been described with the ICL, which is sulcus-fixated.

THE FUTURE OF PHAKIC IMPLANTS

Today, phakic IOLs represent only a small part of refractive surgery indications. However, because of their optical qualities and their theoretical and practical advantages, as well as the contraindications and limitations of LASIK, I initially believed that these implants would make up approximately 20% to 30% of the refractive surgery market. Unlike what I thought some years ago, the market of phakic implants will probably not be as important as first estimated because of the adverse effects we have observed on all types of implants. Their usage will probably only cover 10% to 20% of refractive surgery indications.

Figure 1. The Vivarte presbyopic phakic IOL.

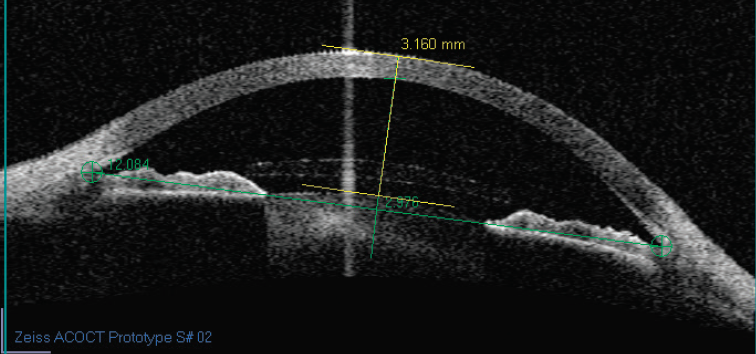

Our experience shows that the key to successfully using angle-supported implants is evaluating the anterior chamber’s internal diameter. Previously, measuring the external white-to-white measurement was imprecise. Today, however, axial imaging techniques that cover the entire diameter of the anterior segment such as the Scheimpflug technique, high-frequency ultrasonographs, and an optical coherence tomographer are in development (Figure 2). Their precision has a 50-µm variation. The software of these devices may shortly be capable of simulating the presence of an implant in the anterior segment, thus indicating whether or not the safety guidelines have been respected.

Figure 2. An anterior segment cut using anterior chamber OCT.

1. Baikoff G, Lutun E, Ferraz C, et al. Analysis of the eye’s anterior segment with an optical coherence tomography: static and dynamic study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1843-1850.

2. Baikoff G, Lutun E, Ferraz C, et al. Refractive Phakic IOLs: contact of three different models with the crystalline lens, an AC OCT study case reports. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:2007-2012.

3. Baikoff G, Bourgeon G, Jitsuo Jodai H, et al. Pigment dispersion and artisan implants. The crystalline lens rise as a safety criterion. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:674-680.

4. Baikoff G, Luntun E, Ferraz C, Wei J. Anterior chamber optical coherence tomography study of human natural accommodation in a 19-year-old albino. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:696-701.

5. Baikoff G, Rozot P, Lutun E, Wei J. Assessment of capsular block syndrome with anterior segment optical coherence tomography. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:2448-2450.

6. Baikoff G, Jodai H, Bourgeon G. Evaluation of the measurement of the anterior chamber’s internal diameter and depth: IOLMaster vs AC OCT. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:1722-1728.

If you perform only LASIK and don’t use phakic IOLs today, you can do better—for your high myopes in particular. I know that’s a bold statement, but I believe it’s true. My opinions are sometimes not popular with some folks in the field, but everyone knows I always tell it as I see it. I expect that phakic IOLs will continue to grow in popularity, especially since the Visian Toric ICL received FDA approval earlier this year.

1. Boxer Wachler BS, Scruggs RT, Yuen LH, Jalali S. Comparison of the Visian ICL and Verisyse phakic intraocular lenses for myopia from 6.00 to 20.00 diopters. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:765-770.

2. Hoffer K. Pigment vacuum iridectomy for phakic refractive lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:1166-1168.