As an anterior segment and glaucoma surgeon, I frequently operate on eyes with a traumatic or uveitic cataract or a cataract from pseudoexfoliation (PXF) syndrome. The health of the zonules is a concern in all these situations. No matter how many maneuvers are performed in the office to predict the status of the zonules, the extent of the zonulopathy is often unknown until a case begins. As Iqbal Ike K. Ahmed, MD, told me, “Complexity is simplicity multiplied.” I bear these words in mind as I approach any cataract procedure. In other words, I proceed under the assumption that zonular weakness is present.

MODIFIED MANUAL FRAGMENTATION

Many surgeons favor a horizontal chop technique for eyes with weak zonules. In the hands of an experienced surgeon, chopping techniques put little pressure and stress on the zonules. Most of my cases, however, are performed with trainees. Often, they struggle with chopping techniques. I find that most trainees push posteriorly when chopping and thus stretch the weakened zonules.

My preferred nuclear fragmentation technique is therefore a modified form of manual fragmentation. First, an initial groove is created with high phaco power. Pushing on the nucleus is discouraged during this step. Once a groove depth of 70% to 80% is reached, the nucleus is cracked with the forces going only laterally. The greatest amount of stress on the zonules occurs during rotation, so after the initial crack, the two hemi-nuclear fragments are removed without rotation.

CASE EXAMPLES

The initial groove and hemi-flip are easy on the zonules. I use the technique in all of my cataract cases—from trainee cases to surgery on eyes with traumatic, dense white lenses. Two case examples highlight how the technique can be used for eyes with different degrees of zonulopathy.

Case No. 1. As a glaucoma specialist, I see a lot of patients with PXF syndrome and cataracts. One such individual was a 78-year-old man who reported experiencing a progressive decline in vision in the left eye.

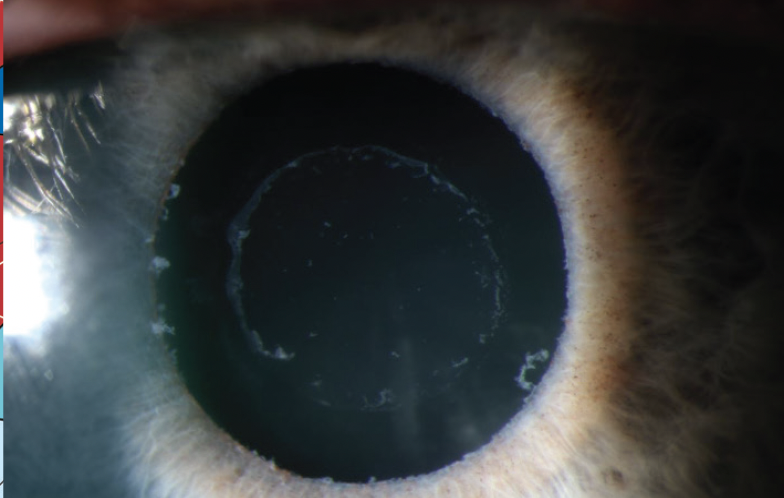

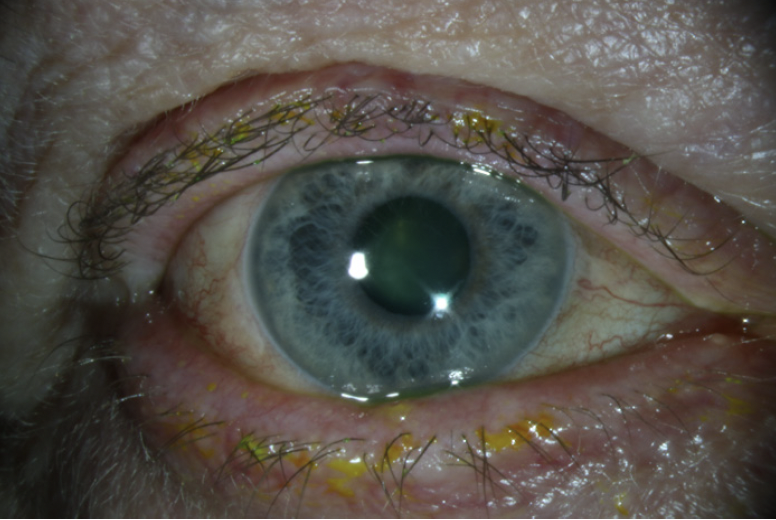

On examination, PXF material was evident on the lens capsule (Figure 1). Poor pupillary dilation made it impossible to determine if there were areas of missing zonules (Figure 2), but there was no frank phacodonesis. The anterior chamber was relatively shallow.

Figure 1. Slit-lamp photograph of PXF material on the anterior lens capsule.

Figure 2. Poor pupillary dilation related to PXF syndrome.

A primary central groove was created, and the nucleus was cracked. The hemi-nuclei were removed without incident, and surgery was straightforward.

Case No. 2. A 36-year-old patient with Marfan syndrome presented with a severely dislocated crystalline lens (Figure 3). An examination found 8 clock hours of missing zonules. After creation of the capsulorhexis, two capsule retractors (MicroSurgical Technology) were placed to support and center the crystalline lens. I find that the primary groove technique works well for dense nuclei that require disassembly. The nucleus in this case was soft. The goal of hydrodissection was therefore to prolapse the lens into the anterior chamber. High vacuum and a low power (epinuclear) setting were then used to remove the lens without ultrasound. At the conclusion of surgery, an Ahmed Segment (FCI Ophthalmics) was sutured inferiorly, and a one-piece IOL was implanted in the bag.

Figure 3. Severely dislocated lens in the eye of a patient with Marfan syndrome.

CONCLUSION

In my experience, the technique I use is gentle on the zonules, efficient, and easy to teach. Success depends on the creation of a large capsulorhexis (≥ 5.5 mm) and complete hydrodissection. These steps facilitate easy removal of the large nuclear fragments. A chop setting can be used with high vacuum to lift the lens into the anterior chamber.