Of all the steps of cataract surgery, the most time is spent discussing methods for nuclear disassembly and efficient phacoemulsification. This is largely because of the step’s importance in terms of both time management and safety.

For most of my cases, my go-to technique is a hybrid of vertical and horizontal chop to fragment the lens nucleus before emulsification. See below to watch a video that elucidates the details and nuances of the chop procedure.

I prefer a chop technique for five reasons:

- No. 1. Chop efficiently divides the nucleus into manageable fragments;

- No. 2. Chop is a safe method for minimizing trauma to the posterior capsule;

- No. 3. With an effective lens isolation technique, chop can minimize stress on the zonules;

- No. 4. Chop can reduce the overall amount of ultrasound energy delivered into the eye; and

- No. 5. When surgical visibility is poor owing to corneal pathology, chop can safely divide the nucleus into fragments.

One of the most nerve-wracking scenarios for cataract surgeons is an eye with corneal pathology that limits visualization during surgery. Groove-based techniques require clear visualization of surgical depth to avoid violating the posterior capsule. In contrast, surgeons can confidently divide cataracts with a vertical chop technique even when visualization is compromised. For this reason, chop is an excellent option for corneal surgeons who combine cataract and endothelial keratoplasty or who frequently operate on eyes with corneal pathology.

GETTING STARTED WITH CHOP

Residents and fellows often are eager to proceed to the steps of surgical training that provide the most exciting and challenging techniques and cases. When refining their phaco skills, however, it is important that surgeons master the instruments they are working with and develop a thorough understanding of different cataract types and their feel.

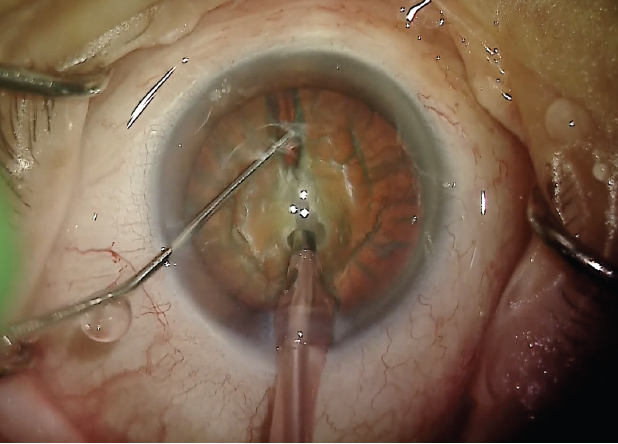

Some barriers to adopting the direct chop technique are a lack of exposure to it during training, failed early attempts at cracking the nucleus that result in fragmented lens pieces, bowl outs, and prolonged surgical times. Starting with a more familiar technique such as stop and chop can allow surgeons to successfully divide the lens into two pieces before beginning to chop each side of the lens into quadrants or sextants (Figure 1). In this situation, the lens nucleus can be removed even if the chop attempts fail because the lens has been divided.

Figure 1. A Nichamin quick chopper is used to divide the lens into two pieces.

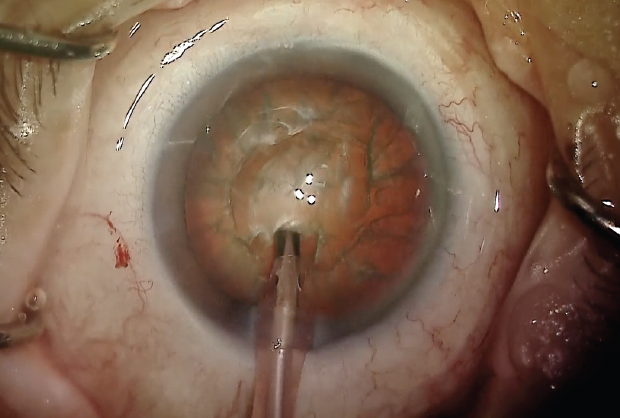

A major mistake that many surgeons new to chop make is not burrowing deeply enough into the cataract with the phaco tip and losing suction when the crack is attempted. By increasing the length of the exposed needle tip beyond the infusion sleeve, more secure suction can be obtained before the chopping instrument is used to cleave the lens fragments. Surgeons who are struggling with this step may find it helpful to make a small crater in the lens in sculpt mode before burying the phaco tip in the chop setting (Figure 2). A firm grasp of the nucleus isolates the lens so that the force used to crack it is applied against the phaco tip rather than the capsular bag and zonules.

Figure 2. A small crater is made at the edge of the lens nucleus.

PREFERRED INSTRUMENTATION

For true vertical chop, it is best to have a sharp or semisharp chopping instrument such as a Nichamin quick chopper to penetrate the nucleus. A more blunt instrument such as a Nagahara chopper is useful for vertical chop with soft lenses and horizontal chop techniques, but this instrument can be a challenge to drive into dense lenses without dislodging them from the phaco tip.

When working with sharp chopping instruments, surgeons must determine their preferred method for removing the final piece of the lens nucleus. With proper fluidics, a stable anterior chamber can be maintained without a second instrument for the final nuclear fragment. Many surgeons, however, use a blunt instrument such as a Connor wand or Drysdale nucleus manipulator to protect the capsular bag from damage by the phaco handpiece if surge occurs.

TECHNIQUES FOR SOFT AND DENSE LENSES

Soft lenses. Chop is my primary nuclear disassembly technique, but it is not ideal for lenses that may not have the density necessary for cleavage planes to be created from single stress points. In this situation, bisecting the lens with a single groove (often preceded by hydrodelineation) can facilitate removal of the two hemi-lenses.

Extremely dense lenses. The lens is removed in its entirety instead of being divided first. Manual small-incision cataract surgery is outside the scope of this discussion, but it is an ideal method for removing the hardest lenses and should be considered when excessive ultrasound energy and manipulation may result in extensive endothelial trauma or zonular loss.