Will COVID-19 change our thinking with respect to immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS)?

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken the world and medicine by storm, and it is hard to imagine that any medical reader is unaware of the numerous issues that have arisen in relation to the virus formally known as SARS-CoV-2. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to see as few patients as infrequently as possible to minimize risk of transmitting the virus. Does this situation add to the already substantial arguments in favor of ISBCS? I would argue that it does.

Many patients and families prefer ISBCS because it entails fewer visits, but there is little benefit for the surgeon in this arrangement. Perhaps now is the time to look at our patients as customers and do what is likely safer and certainly more convenient for them.

PREVENTING THE SPREAD

When I was asked to write about how the pandemic may change our thinking about ISBCS, my first thought was that readers would think I am taking opportunistic advantage of one of the worst pandemics ever to strike humanity to push ISBCS. I have no intention of acting like a toothbrush salesman during the Black Death. However, I would like to explain what I have learned over the past 2 months and suggest some things that we can potentially do better.

It was interesting and unfortunate that most Western societies (except the Czech Republic) did not learn from our friends in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore that requiring everyone to wear masks—whether surgical, N95, or homemade—can flatten the epidemic curve. The efforts in those countries significantly reduced morbidity and mortality rates.

Countries that adopted universal masking rapidly curtailed the epidemic. By contrast, most that did not failed to prevent explosive spread of COVID-19, resulting in strained medical systems. In some cases, doctors were forced to triage patients with the best chances of survival to the treatment group but leave others to their moribund fates.

Many countries found excuses to avoid deploying massive responses such as closing restaurants, limiting peoples’ movements, outlawing gatherings, and enforcing social distancing. Their justifications might have made some sense to individuals without a background in epidemiology or microbiology, but to most of us in medicine the lack of even broader and quicker response was flawed (see Understanding the Spread). Many leaders educated only in politics and economics who are searching for economic stability or advantage over others might unwisely think or wish that, “It can’t happen here.” Those individuals, too, might deny the need for avoiding gathering in parks and stopping flights to infected or questionable locations, among other aggressive shifts in societal practices.

LESSON FROM HISTORY

In 1918, America was deeply engaged in raising money for World War I. On September 28 of that year, the city of Philadelphia put on a huge Liberty Loan Parade. Despite medical warnings about influenza, and despite that the war was all but over, marchers stepped out to perform what they saw as their patriotic duty. Within 2 days of the parade, influenza struck fiercely in Philadelphia, and people feared that the Black Death of the middle ages had returned.1

Our position with COVID-19 is not dissimilar from that during the Great Influenza of 1918 to 1920. We have zero immunity. We have no vaccines, no convalescent serum with which to treat patients, and no drugs known to be efficacious against the disease. COVID-19 is an RNA virus, with a similar rate and method of spread to influenza. The best treatment in use in much of the world is social distancing, which is the same method that finally achieved some success with influenza in the early 1900s.

Understanding the Spread

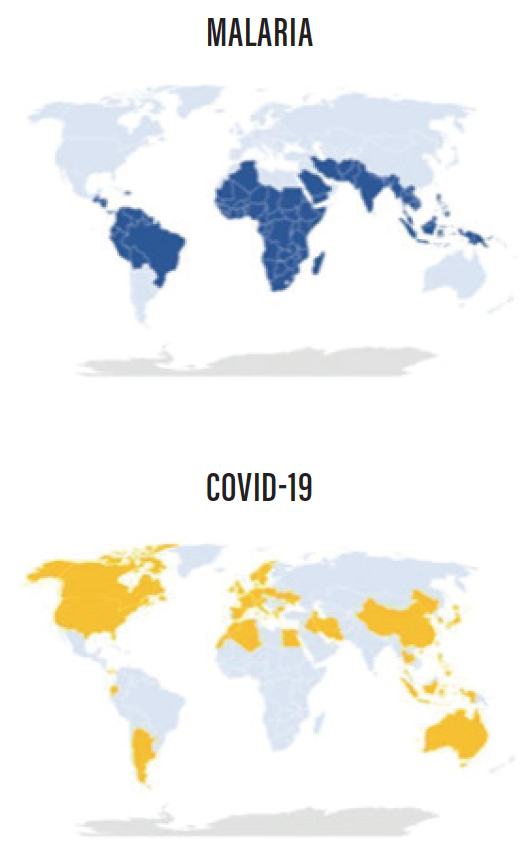

During any crisis, we look for reasons why the crisis will not affect us. Figure 1 illustrates how those living in countries where malaria is endemic seem to be relatively safe (so far) from COVID-19.

Figure 1. Countries where malaria (blue, top) and COVID-19 (yellow, bottom) have caused more than 0.1 deaths per million inhabitants. Sources: ourworldindata.org (top) and worldofmeters.info (bottom). March 14, 2020.

Research suggests that the temporal and geographic spread of COVID-19 seems to align with the density of global air traffic (Figure 2). That difference is the vector. For COVID-19, the vector is people, not mosquitoes.

Figure 2. The global aviation network. Note that air travel to most places in Africa, regions of South America, and parts of central Asia is low. If travel increases in these regions, additional introductions of vector-borne pathogens are probable. Source: Kilpatrick AM, Randolph SE. Drivers, dynamics, and control of emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Lancet. 2012;380(9857):1946-1955.

Many of our assumptions about this virus may not be correct or may not account for an observation completely.

PATIENT AS CUSTOMER

How does all of this relate to the practice of ophthalmology and how we perform our surgeries? In Canada—and as far as I know in other Western countries—medicine has changed drastically since I was a resident. When I was training, in the late 1970s, ophthalmologists spent a lot of time with each patient. They even did their refractions and answered patients’ questions. I suspect that the nature of practice at that time was because the patient was paying the doctor, and, if the doctor did not come off as considerate and diligent, the patient did not return.

We now work under various third-party payers, whether government or private insurance, and it is unusual for the patient presenting for cataract surgery to be our customer. Almost universally, these patients will be covered, and their care is paid for by government or insurance, not the patient.

All purveyors of goods and services work to satisfy their customers. However, in medicine, the patient is no longer the customer, the payer is. Third-party payers have demanded progressive decreases in fees and are not interested in whether the doctor spends a lot of time with the patient.

If the patient was our customer, we would want to minimize visits and optimize convenience for the patient and his or her family, without sacrificing the quality of the result. When the patient is not the customer, there is no potential gain for the doctor when visit numbers are decreased. Therefore, there is real financial loss to the doctor in almost every jurisdiction if the patient undergoes ISBCS rather than delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery (DSBCS). Consequently, in this scenario, it is easy for the doctor to think of every possible excuse to perform DSBCS rather than ISBCS.

In our current reality, doctors do not want to undertake greater complexity in their surgeries—and perhaps slightly increased personal risk if a complication should occur—when they also lose money. Furthermore, the actual customer, the third-party payer, sees no benefit and could not care less if ISBCS or DSBCS is done, nor how many visits are required. Often, the payer—the customer—hopes that only one eye ever gets done; it’s cheaper that way.

FEWER PATIENTS, SAFER SURGERIES?

How does COVID-19 affect our thinking? Today, when we see a patient during times of social distancing and lockdown, because of the proximity necessary for an eye examination, we are risking both the patients’ and our own lives. We would like to see one patient at a time and then scrupulously clean the room. However, if we do that, we lose money.

Would we perhaps be safer if we performed the same number of surgeries per day on half as many patients? By performing ISBCS, we could do that with fewer staff members, less commotion in our ORs, and less risk of viral transmission to all concerned.

COVID-19 will not go on forever, but other contagious diseases are bound to follow. Perhaps if we were slower, performed ISBCS, and operated on fewer patients per day, we would also slow the development of bacterial resistance to our antibiotics. It is unquestionable that allowing fewer patients to congregate in waiting rooms provides less chance of them picking up each other’s pathogens.

Perhaps our whole concept, foisted upon us by third-party payers who want to reduce fees—forcing us to do more cases per day to support our staff and offices, teaching us to achieve this by doing less to each patient per visit—should be reversed, and the patient should return to being the customer.

MEDICAL MODELS

When I was in medical school at Baylor College of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey, MD, the college’s president at that time, would bring an outstanding lecturer to speak to the entire medical school each week. One day, the lecturer was a Harvard economist who was asked to tackle the topic of whether the United States should adopt universal health care, as Canada had done.

As the only Canadian (and the only foreigner) in my class, I was highly interested. The lecture was brilliant, not emotional, not looking at what was cheaper, but simply delving into the expected behavior of each participant in each system and the likely consequences of that behavior.

I have since seen just about everything that economist said come true on both sides of the Canada-US border. If you go to a Blue Jays versus White Sox baseball game and look up into the stands, whether in Toronto or Chicago, it will be obvious that the average Canadian looks healthier than the average American. We attribute this difference to our free-to-the-patient health care system.

On the other hand, America supports far more research and has many more top-level medical and research institutes than Canada. Affluent Canadians do not hesitate to go south if they perceive that the care they can buy in the United States is better for their problem than what the government will provide for free in Canada.

Everybody fights over limited dollars in Canada, and no group is happy. Americans just raise their rates—but then fewer Americans can afford the best care. On both sides, something valuable gets traded away and is lost to the people.

From what I can see, the Harvard economics professor was spot on: We should all have catastrophic coverage as a right of every citizen, but when the government totally takes over health care and the patient ceases to be the customer, the patient must beware the loss of his or her rights in the field that matters to us most in life—our health. A mixed system is probably best.

COVID-19 is teaching us that the time has come for us to once again treat the patient as the customer. We should simply do what is in the best interest of the patient and his or her family—not the third-party payers, not the politicians, not the doctors, only the patient. ISBCS seems to fit this new, old paradigm.

1. Barry JM. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Viking; 2004.