CASE PRESENTATION

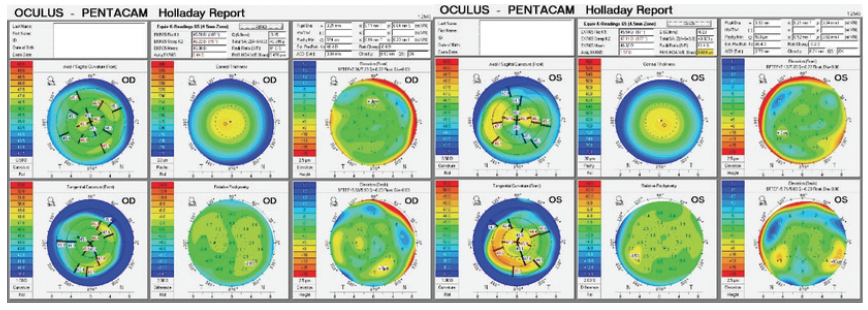

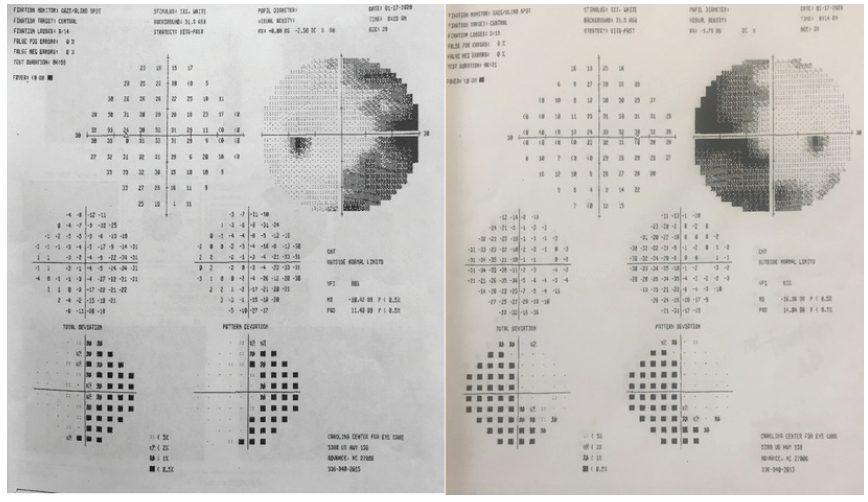

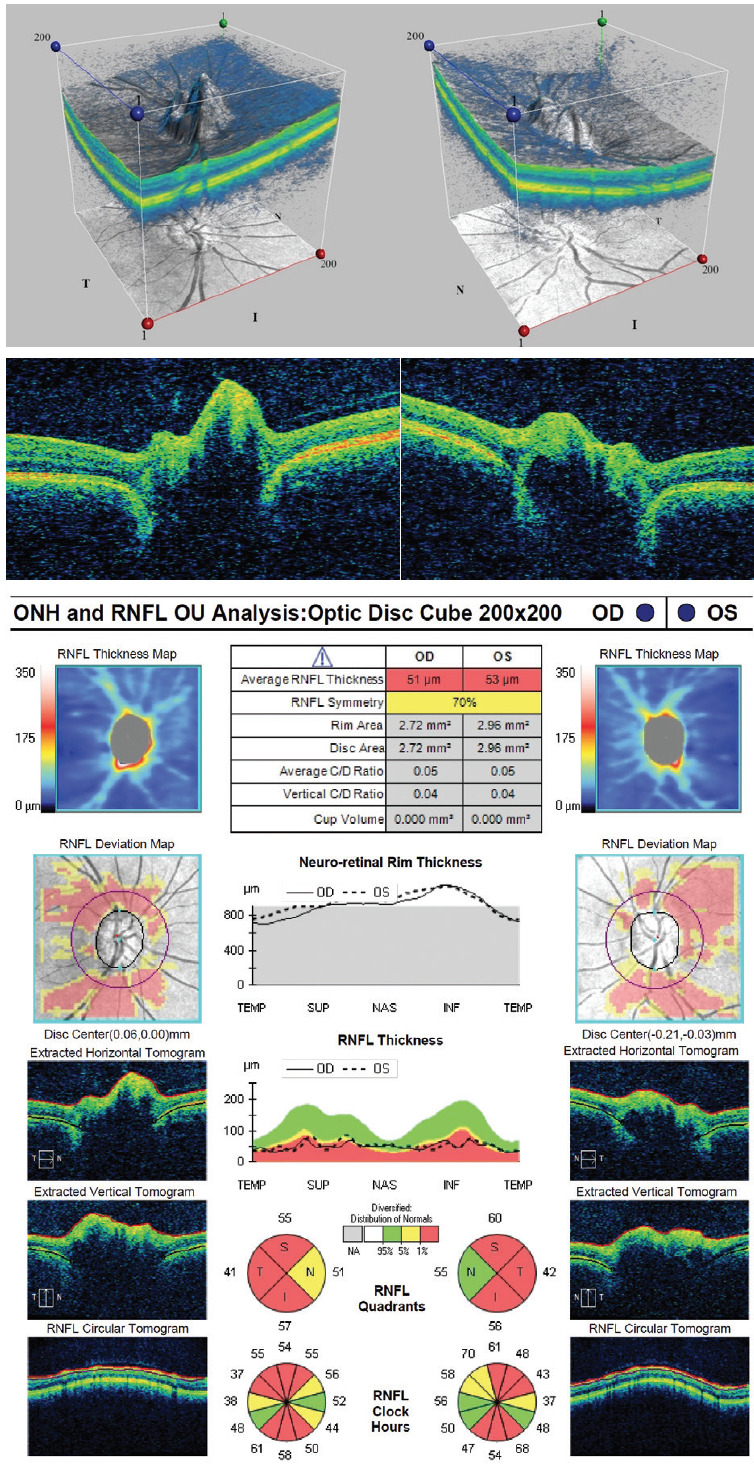

A 28-year-old woman presents for a routine evaluation for refractive surgery. The patient’s manifest refractions are -5.25 +0.50 x 180º OD and -6.00 +2.50 x 004º OS. Analysis with the Pentacam (Oculus Optikgeräte) shows normal pachymetry in each eye, minimal astigmatism in the right eye, and moderate astigmatism in the left eye (Figure 1). Visual field testing reveals a binasal hemianopia (Figure 2). OCT imaging shows optic nerve head drusen (Figure 3). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the optic nerve head and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbits with and without contrast reveal only optic nerve drusen. How would you proceed?

Figure 1. Imaging with the Pentacam.

Figure 2. Visual field testing (Humphrey Field Analyzer, Carl Zeiss Meditec) reveals a binasal hemianopia.

Figure 3. OCT imaging shows optic nerve head drusen.

—Case prepared by Karl G. Stonecipher, MD

CHRISTOPHER E. STARR, MD

I would not offer this patient elective refractive surgery for two reasons. First, she is young and unfortunately already has significant visual field loss from optic nerve head drusen. Although progression is difficult to predict in cases such as this, I am worried about the early severity combined with the fact that no treatment is currently available to reverse or stabilize drusen and the field loss they cause.

Second, I am a bit concerned about the corneas, particularly the cornea of the left eye. It exhibits moderate irregular astigmatism, abnormally steep keratometry (> 47.00 D), and an against-the-rule, crab claw–like topographic pattern. Despite a normal pachymetry reading and posterior float, my suspicion of ectasia (eg, pellucid marginal degeneration) is high based on the patient’s age and the suggestive topographic pattern.

I would likely rule out refractive surgery for this patient based on each of these issues individually. The presence of both is a guaranteed “no go” for me. I would refer her to neuro-ophthalmology for an evaluation of the optic nerve drusen and to optometry for a contact lens fitting (rigid gas permeable lenses may be the best option). I would see her again in my clinic in 6 to 12 months for repeat refractive and corneal testing. If the corneas exhibit signs of progressive ectasia, I would offer her CXL for corneal stabilization.

RONALD R. KRUEGER, MD, MSE; AND IVEY L. THORNTON KRUEGER, MD

The fact that this patient has significant optic disc drusen and significant bilateral visual field defects warrants caution. The first step before proceeding is to ensure stability of the refraction and visual field loss. As a fellowship-trained neuro-ophthalmologist (I.L.T.K.), my attention is drawn by the crowded optic discs and visual field deficits, which increase this patient’s risk of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) if the IOP rises during refractive surgery.1-4 The main concern relative to AION is the placement of a suction ring on the eye for LASIK. Although the incidence of AION is rare, the condition has been associated in cataract surgery with a postoperative IOP elevation.

For this reason, we would consider PRK with adjunctive mitomycin C but not LASIK. Because even a postoperative IOP rise is a concern, we would recommend frequent postoperative visits to detect a steroid response and treat one accordingly. Although the patient has mildly irregular against-the-rule astigmatism, the corneal thickness, the steepest keratometry reading, the posterior surface elevation, and her age make it reasonable to consider a PRK procedure using a sufficiently large optical zone to minimize aberration-induced contrast losses. We have never performed PRK on a patient such as this one, but we think the procedure, after appropriate informed consent, could be successful.

JULIE SKAGGS, MD

I do not perform corneal refractive surgery, so I do not feel qualified to comment on whether this patient should undergo one of those elective procedures. As a fellowship-trained neuro-ophthalmologist, however, I agree that imaging the optic nerves and chiasm is the first step. Although chiasmal pathology is always a concern when a bitemporal defect is present, a binasal defect can also be caused by chiasmal pathology affecting the outer temporal fibers that do not cross.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the orbits with and without gadolinium, paying attention to the optic nerves and chiasm, would be a good choice. There are case reports of an aneurysm’s causing binasal defects, so I would consider obtaining magnetic resonance angiography or CT angiography as well. Given the low likelihood of an aneurysm, however, I would order one of these tests only if there were no other possible explanation (not the case with this patient).

Because a CT scan is available, I would evaluate it for confirmatory calcium deposits. In general, when I see patients with optic nerve head drusen, I like to confirm their presence with either fundus autofluorescence (if the drusen are visible) or a low-gain B-scan (if the drusen are buried).

Some ophthalmologists, myself included, believe that avoiding ocular hypertension in patients such as this one likely protects them against further optic neuropathy. Normal-tension glaucoma cannot be diagnosed in these patients because the cup is not visible, so prophylactically avoiding ocular hypertension in these patients makes sense to me. It would be rare but possible for one of these patients to experience significant vision loss from optic nerve head drusen because one of the differential diagnoses of bilateral central islands of vision (also known as gun-barrel visual fields) is bilateral optic nerve head drusen. The other etiologies in this differential diagnosis are retinitis pigmentosa, burnt-out papilledema, end-stage glaucoma, paraneoplastic optic neuropathy, functional vision loss, and bilateral posterior cerebral artery infarcts with macular sparing. There have also been reports of AION associated with optic nerve head drusen, even in young patients, and their optic discs are certainly at risk.

Any procedure that can raise the IOP, such as LASIK, likely increases the risk of AION in a patient with optic disc drusen. At the very least, this information should be included in the preoperative discussion.

WHAT I DID: KARL G. STONECIPHER, MD

After detailed informed consent, the patient elected to proceed with epi-Bowman keratectomy PRK. Surgery was uncomplicated, and reepithelialization was unremarkable. Three months after surgery, UCVA was 20/20 OU. The patient reported improvements in overall quality of vision, quantity of vision, and peripheral vision.

1. Mansour AM, Shoch D, Logani S. Optic disk size in ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106(5):587-589.

2. Feit RH, Tomsak RL, Ellenberger C Jr. Structural factors in the pathogenesis of ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98(1):105-108.

3. Beck RW, Savino PJ, Repka MX, Schatz NJ, Sergott RC. Optic disc structure in anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91(11):1334-1337.

4. Doro S, Lessell S. Cup-disc ratio and ischemic optic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(8):1143-1144.