Of the more than 70,200 drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2017, approximately 68% involved an opioid. The number of deaths involving prescription and illegal opioids in this country was six times higher in 2017 than in 1999, and that number continues to grow.1 Not surprisingly, the scope of this crisis has spurred action. State attorneys general have brought lawsuits against opioid manufacturers. In September, Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin (oxycodone HCL), filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy as part of a tentative settlement with many of the state and local governments that have sued the company.

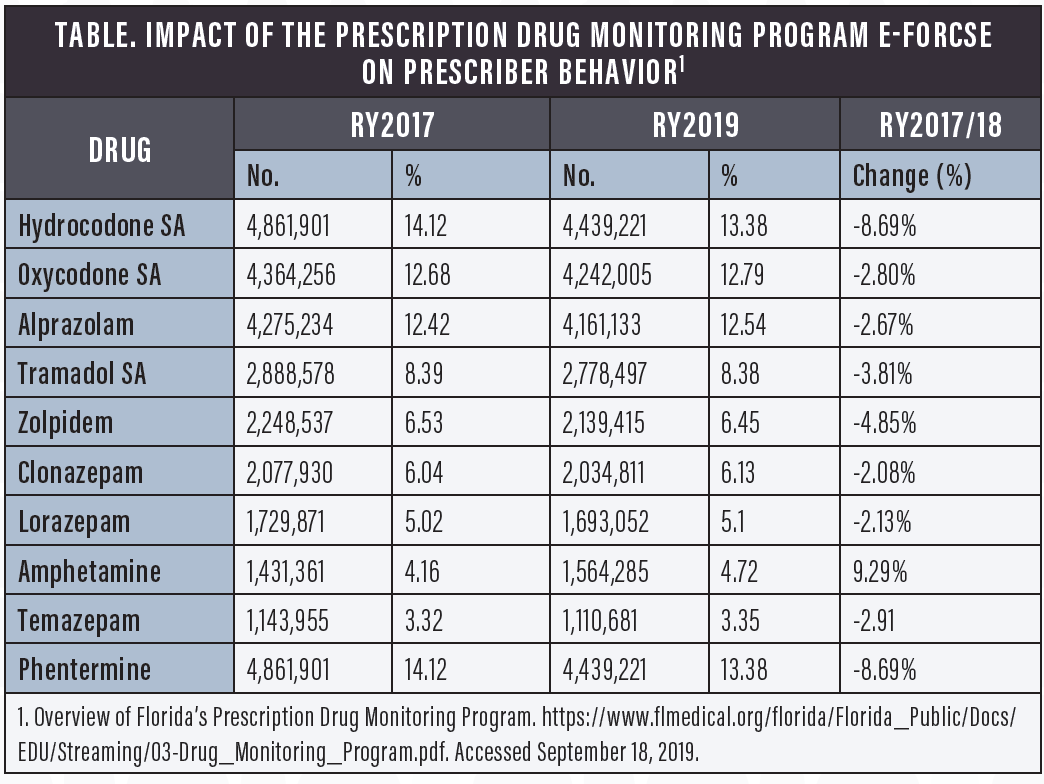

States are also increasing their oversight of drug prescriptions. My state legislature created the Florida prescription drug monitoring program known as E-FORCSE (Electronic-Florida Online Reporting of Controlled Substance Evaluation Program). Before I can prescribe a pain medication, I must log into the E-FORCSE database to review all of the narcotics that have ever been prescribed to a patient and assess his or her theoretical risk of addiction to pain medication (Table).

Fortunately, the role of opioids in ophthalmology is limited. In my practice, for instance, we might prescribe it for the occasional post-PRK patient. But even this is extremely rare, and we tend to tell patients who ask for an opioid that we are unable to prescribe one to them.

A FINE LINE

The issue of ethically prescribing products is germane to this specialty in other ways. One such area is over-the-counter (OTC) therapeutics.

As I see it, the problem with eye care providers selling OTC products occurs when they do so at substantially inflated prices. Vitamin supplements are a case in point. It is perfectly reasonable for physicians to recommend that patients with macular degeneration begin taking nutritional supplements containing an Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) formulation and for these doctors’ practices to sell these vitamins. I would argue, however, that some providers cross an ethical line by selling their own specially compounded AREDS-2 supplement at a much higher price than similar OTC products available elsewhere or by claiming that their supplement offers better absorption or efficacy without evidence from a clinical trial to support those claims.

OTC PRODUCTS SOLD IN MY PRACTICE

My practice does not sell a lot of OTC therapeutics, but, with those that we do, our goal is to maximize convenience for our patients, not profits for the practice. Two OTC products that we offer are hypochlorous acid solution spray and brimonidine tartrate.

No. 1: Hypochlorous acid solution spray. Hypochlorous acid solution spray can be useful for the treatment of blepharitis. Although Ocusoft Hypochlor spray 0.02% (Ocusoft) is available OTC, my patients report that it’s increasingly hard to obtain. For that reason, we stock it in our office so that the product is readily available to our patients, and we price it similarly to its retail price at local drugstores.

No. 2: Brimonidine tartrate. Before it became widely available, my practice began selling brimonidine tartrate ophthalmic solution 0.025% (Lumify, Bausch + Lomb) to patients. A lot of patients present to my practice with a complaint about red eyes, and many of them are using a product such as tetryzoline (Visine, Johnson & Johnson Vision), which can cause rebound hyperemia. I switch these patients to brimonidine tartrate ophthalmic solution. Because several patients have become confused and have reported difficulty in finding the product at the drugstore, we continue to sell it at the office for a price similar to its typical retail cost.

CONCLUSION

Most physicians whose practices sell OTC therapeutics directly to patients do so for patient convenience and to improve quality of care. Providers who substantially inflate the prices of OTC products run the risk of discovery in addition to the ethical questions that their actions raise. After all, a large proportion of patients are cost-conscious, and they can search the internet on their smartphones. If price shopping leads them to suspect that they are being overcharged, they may look elsewhere for care, and they will likely share their experiences with others.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid Overdose. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Accessed September 16, 2019.