The human lens is one of the most interesting anatomic structures in the body. Despite our collective zeal for removing and replacing it, occasionally we should step back and marvel at this masterpiece.

The lens is one of the first structures to develop embryologically, being formed from the lens plate at around gestational day 27. From there, the lens progresses in developing the embryonic nucleus, the fetal nucleus, and Y sutures. Continued differentiation produces the anterior lens epithelial cells and the anterior and posterior lens capsules. At birth, the lens weighs approximately 90 mg, which increases by about 2 mg per year through the addition of new lens fibers.

The human lens is an active, growing, changing, beautiful mechanism that can provide up to 16.00 D of accommodation. The bravado with which we recommend cataract surgery must be balanced by recognition that we are not replacing the cataract with equipment that will match the potential function of an ideal human lens. Nevertheless, we have provided millions of patients with amazing results despite our limitations.

With this sobering information in mind, I would ask every ophthalmologist to pause and attempt to think differently about IOLs and the variables that prevent perfect outcomes. With current technologies, most of us are within ±0.50 D of our target refraction 60% to 80% of the time, depending on technique, biometry, and formulas used.1,2 Even when we hit the target, however, we are still stuck with the all-too-common and often bothersome symptoms of positive and negative dysphotopsias.

If we are trying to correct astigmatism, we face yet another set of variables. The ability to properly quantify the magnitude and axis of astigmatism varies among machines, and, although our average amount of surgically induced astigmatism is typically low, it can vary greatly from patient to patient. Then there are the factors of marking the correct axis, implanting the lens on that axis, and hoping the lens does not rotate postoperatively.

Add the correction of presbyopia to the mix, with accommodating, multifocal, or extended depth of focus lenses, and the variables for achieving a great outcome are exponentially increased. Although there has never been a better time to have cataract surgery in human history, there is no doubt that the future will hold better options.

ACCESS TO THE FUTURE

In this world that is in a constant state of technological evolution, how can we give our patients access to future improvements in lens design? This is a question that keeps me up at night and thinking during the day.

At some point in the future, we will likely solve the puzzle of accommodation. When we can routinely provide 5.00 to 10.00 D of accommodation with a lens that is adjustable through noninvasive means, we will have reached a new plateau in refractive cataract surgery. This may sound like a search for the holy grail or the fountain of youth, but I believe we are within 20 years of this achievement. Imagine reading glasses as a mark of cataract surgery today, prior to this new dawn, just as aphakic spectacles were a mark of cataract surgery before the popularization of IOLs.

Personally, I want all of my patients to be able to take advantage of the best lens technology when it arrives. At this time, however, patients have only one chance to make a decision on lens technology that will affect their quality of life every moment they are awake for the rest of their lives. With limited options, the fear of having surgery, confusion about the available lens options, and concern about the financial implications of their choices, most patients are in a compromised position to make their best choice.

LOOKING AHEAD

What does the future hold? For all of the reasons outlined, I strongly believe that adjustable and exchangeable lenses are within the realm of possibility for the future of IOLs. At this point, achieving emmetropia is about the best outcome we can hope for. Unfortunately, this doesn’t happen for most patients—there are just too many variables to control for, and many surgeons don’t correct astigmatism at the time of cataract surgery (which is another topic for another time).

Some patients have aberrated corneas from previous radial keratotomy, PRK, or LASIK, making lens choice even more difficult. Although pseudophakic excimer laser enhancements are relatively straightforward for myopic corrections, IOL exchanges are still necessary to correct large hyperopic refractive misses. There is clearly an unmet need with regard to routinely achieving emmetropia for our patients. Fortunately, there are three emerging adjustable IOL technologies that aim to address this.

RxLAL. RxSight (formerly Calhoun Vision) right now has the only FDA-approved technology that allows noninvasive alteration of lens power. The labeling of the company’s Light Adjustable Lens (RxLAL) is for correction of up to 2.00 D of postoperative sphere and/or -0.75 to -2.00 D of residual postoperative refractive cylinder.3 According to FDA data, patients achieved 20/20 visual acuity at 6 months at a rate twice as high as patients receiving standard IOLs. This is a technology that has been anticipated for some time, and it marks a big step forward in our chase of perfection.

Perfect Lens. Another company, Perfect Lens, is approaching noninvasive adjustment of IOL power through a different mechanism. The company’s developers have found a way to alter the power of a hydrophobic IOL through a technology called phase wrapping. In this process, a femtosecond laser applies a pattern of spots to the lens, thus creating a lens within the lens, using Fresnel optics. The laser energy changes the relative hydrophilicity of the acrylic lens, thereby changing the refractive index.4 The technology can theoretically be used with any hydrophobic acrylic lens, and it has been shown to create highly accurate power changes of up to 3.60 D. It can correct sphere and cylinder and even create or reverse multifocality. If this technology pans out, it could be disruptive to the IOL industry, as we would no longer need large consignments of premium IOLs. The desired characteristics could be written onto the lens postoperatively. (For more information on the Perfect Lens, see “IOL Power Adjustment by Femtosecond Laser”, pg 52.)

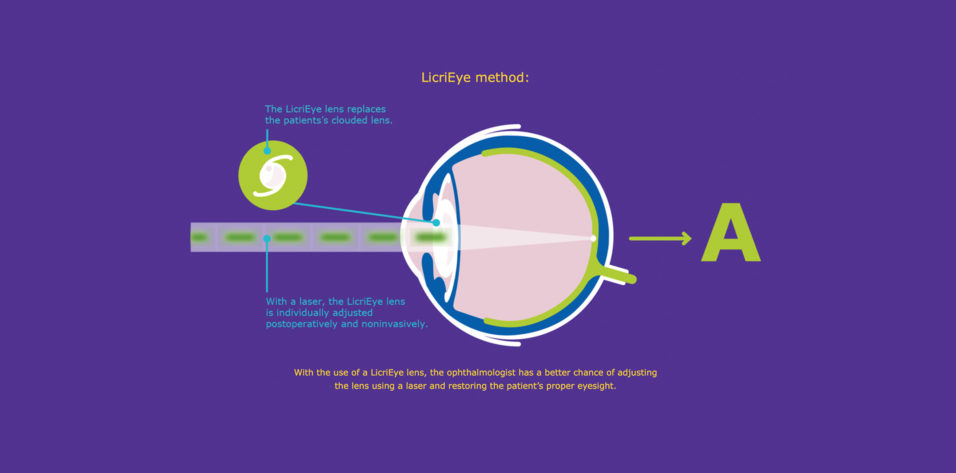

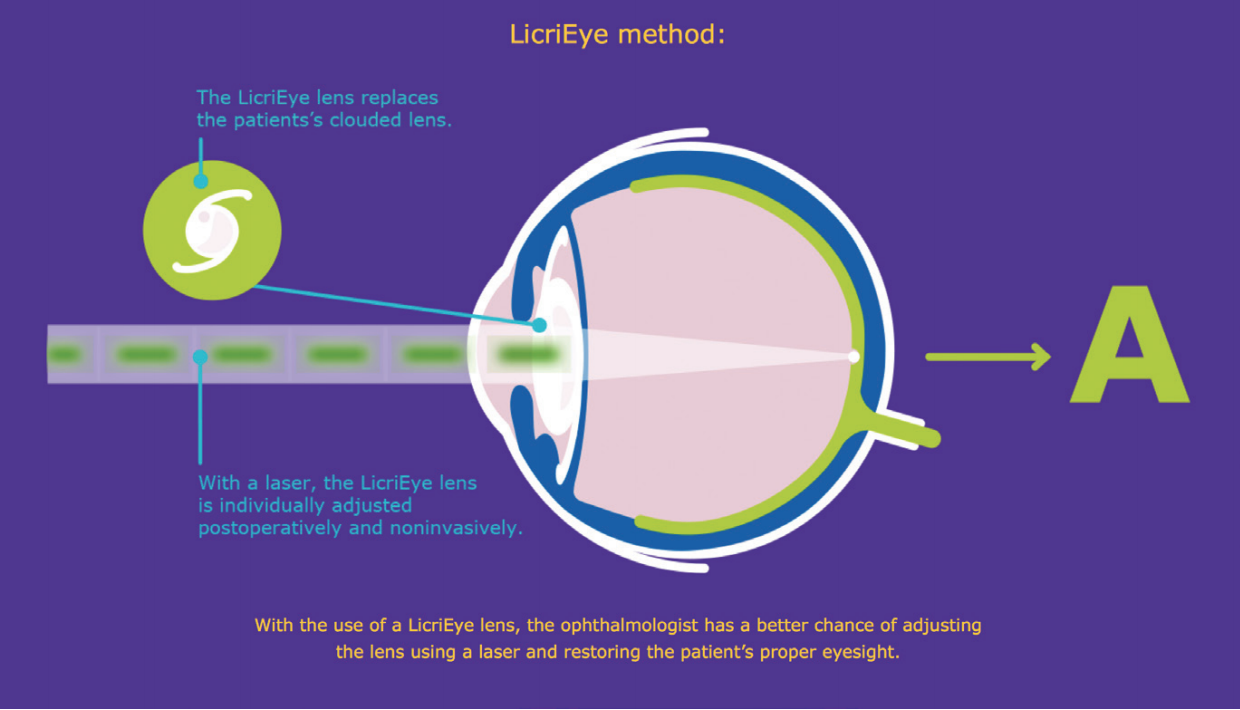

LicriEye. Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany is developing yet another technology, dubbed LicriEye, for postoperative lens power adjustment.5 This technology is based on a proprietary reactive mesogen material. Mesogens are compounds that display properties similar to those of liquid crystals. The material is flexible and has been used in other applications such as in LCD and OLED displays to help improve the optical quality of images. The mesogens can be altered postoperatively using noninvasive methods that have not been fully disclosed (Figure). Although little information is publicly available, this may be a technology worth watching.

Figure. Schematic of the LicriEye.

Courtesy of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany

ADJUSTABLE TECHNOLOGY

Noninvasive postoperative adjustment of lens power sounds appealing, but I am more excited about technology that can be upgraded over time. Remember, the lenses we implant today pale in comparison to the natural lens—and, one would hope, in comparison to the lenses of the future. By closing the door to exchanges or upgrades of technology, we are essentially putting a time-stamp on every eye we operate on.

Imagine if Array lenses (Advanced Medical Optics; no longer available) could have been upgraded with characteristics similar to those of AcrySof IQ ReStor (Alcon) or Tecnis Multifocal (Johnson & Johnson Vision) IOLs. And imagine if they could then be further upgraded with characteristics of ReStor Activefocus (Alcon) or Symfony (Johnson & Johnson Vision) IOLs.

Within the span of 10 years, we have seen dramatic improvements in the types of IOL optics available. Imagine what the next 10 years will hold. That’s why I’m enthusiastic about two modular IOL technologies now in development, the Harmoni Modular IOL (ClarVista Medical)6 and the Precisight (InfiniteVision Optics).7 Both ClarVista (acquired by Alcon8 in 2017) and InfiniteVision have created multicomponent IOL designs that consist of a base plate with haptics that accepts proprietary exchangeable optics. The optics can be removed while the baseplate and haptics remain in place. This will make the process of exchanging or upgrading IOLs easier to recommend in the event of a refractive surprise, multifocal intolerance, or the emergence of a technology upgrade. Each device has received the CE Mark, and both companies continue to make progress on further approvals.

The last technology I will mention is the Gemini Refractive Capsule (Omega Ophthalmics).9 Full disclosure: I am the inventor of this technology and a cofounder of the company. The Gemini Refractive Capsule is designed to be an open-access platform that keeps the capsular bag open. It is designed to hold all traditional C-haptic IOLs from any manufacturer, as well as a proprietary lens design, providing maximal flexibility for surgeons creating solutions for patients.

Lenses can be added rather than simply exchanged. Also, for patients with low vision, a reverse Galilean telescope can be assembled inside the open space. Further, the Gemini Refractive Capsule has the ability to hold technology such as IOP sensors and sustained-release drugs or drug delivery devices.

The human lens capsule is precious real estate within the eye, and keeping that inert space open for future options is a value proposition that patients and doctors may find attractive.

CONCLUSION

The future is coming. Perhaps it is already here. We must do everything in our power to leverage the collective creativity of physicians, engineers, and materials scientists to continue moving the needle. The human lens is a work of wonder, and we need better designs to mimic its natural functions as well as less invasive ways of correcting refractive misses.

I am amazed at the advances I have witnessed in my first 10 years in ophthalmology, and I can’t wait to see what is waiting for us in the next 20 to 30 years. I just hope the patients on whom I operate today will have the opportunity to use those technologies as they become available.