Efforts to minimize or even eliminate traditional postoperative topical medications after cataract surgery have gained attention over the past few years. More surgeons are interested in effective strategies to develop a truly dropless cataract surgery experience. Dropless strategies primarily involve injecting antibiotics, steroids, and/or nonsteroidal medications into the anterior chamber, intracapsular space, or the vitreous cavity.

My preferred strategy since 2014 has been to inject Tri-Moxi (triamcinolone 15 mg/mL and 1 mg/mL moxifloxacin, ImprimisRx) into the vitreous cavity with a 30-gauge needle via a pars plana approach, at a location approximately 3.5 mm posterior to the surgical limbus. The intravitreal antibiotic steroid (IVAS) injection is performed after routine and uneventful cataract surgery. Some ophthalmologists may wonder why they should consider a dropless approach when topical medications can be adjusted as needed and, perhaps more importantly, are familiar to both surgeons and patients.

ADVANTAGES

To my mind, there are four advantages of IVAS.

No. 1: Cost savings. Postoperative topical therapy can range in cost from $50 to $300 per eye, but some out-of-pocket copayments are as high as $650 per eye. IVAS therapy costs $22 per vial, which is borne by the surgery center. A study cosponsored by Cataract Surgeons for Improved Eyecare (improvedeyecare.org) found that dropless therapy could save the CMS more than $7 billion and patients about $1.4 billion in out-of-pocket costs in a 10-year period.1

No. 2: Improved compliance. Multiple studies indicate that patients can struggle to use their medications correctly.2-4 Poor compliance is multifactorial, and injecting medication into the eye, as opposed to applying it on the eye, offers advantages.

No. 3: Less ocular surface damage. Topical medications can cause and exacerbate ocular surface disease through multiple mechanisms. IVAS reduces the risk of corneal toxicity by eliminating preservative-containing topical medications that cause ocular surface damage, ranging from allergic reactions to direct epithelial toxicity. The negative effects of the preservative benzalkonium chloride are well known.

No. 4: Fewer calls to the office and staff. IVAS can reduce the number of labor-hours spent by office staff talking to patients about their drug regimens, obtaining prior authorizations from insurance companies, and talking to pharmacists about alternative medications if a certain topical medication is not covered by insurance. On a personal note, I have had two incidents when a pharmacist replaced a noncovered topical NSAID with topical proparacaine without consulting me.

DISADVANTAGES

Admittedly, IVAS therapy is not without potential limitations and risks.

No. 1: Concerns about compounding pharmacies. There has been significant concern that triamcinolone-moxifloxacin injections prepared by 503A pharmacies can cause endophthalmitis.5 It is vital for any surgeon choosing to use IVAS to understand the difference between a 503A and 503B pharmacy and to use only medications from 503B pharmacies for intraocular injection. I have and will only use Tri-Moxi.

No. 2: Complaints from patients. Patients may report minor pain, floaters, and subconjunctival hemorrhages in the immediate postoperative period. It is important to discuss the possibility of these phenomena with patients prior to cataract surgery, especially if they have chosen to receive a premium IOL and if they have certain postoperative visual expectations.

No. 3: Continued inflammation. This is probably the greatest concern with IVAS therapy, because some patients demonstrate continued inflammation after surgery. It is likely that patients with proinflammatory ocular pathologies such as diabetic retinopathy, uveitis, and epiretinal membranes; those who have undergone laser cataract surgery; and those with dense cataracts or wet age-related macular degeneration will require supplemental topical antiinflammatory medications.

No. 4: Catastrophe. A joint task force formed by the ASCRS and ASRS reported a strong association between hemorrhagic occlusive retinal vasculitis and the use of intraocular vancomycin.6 Since this statement was issued, most surgeons have stopped using vancomycin, and no cases of hemorrhagic occlusive

retinal vasculitis have been reported with a triamcinolone-moxifloxacin combination only. ImprimisRx no longer makes Tri-Moxi-Vanc.

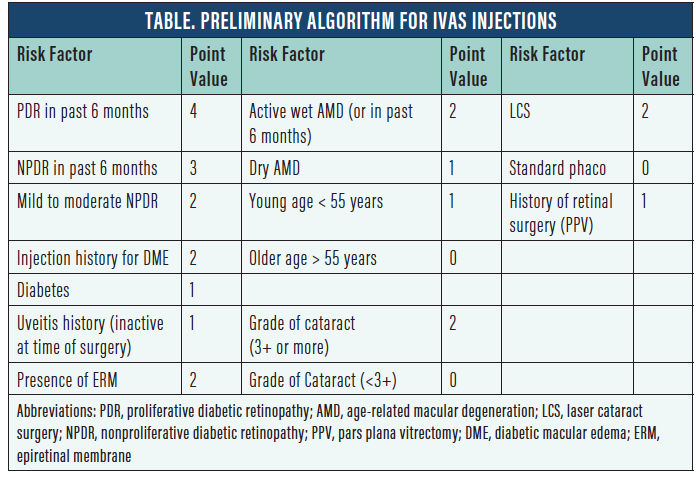

WHEN TO SUPPLEMENT

Some patients, based on risk factors, will require supplemental topical antiinflammatory medications after an IVAS injection. Based on the risk factors outlined in the Table, I propose stratifying cataract surgery patients into three categories:

1. Low Risk (0–4 points): Can safely receive IVAS without supplemental topical antiinflammatory medications;

2. Medium Risk (5–7 points): Can receive IVAS, but surgeon should strongly consider supplemental topical antiinflammatory medications; and

3. High Risk (7+ points): Can receive IVAS but must also receive supplemental topical antiinflammatory medications.

In my current practice with IVAS, I give all diabetic patients topical NSAID medications. For patients at medium-risk, I prescribe either a twice-daily topical steroid (loteprednol) or a topical NSAID (bromfenac administered daily or ketorolac administered three times daily) for 6 weeks. For patients at high-risk, I prescribe a twice-daily topical steroid and a topical NSAID, either bromfenac daily or ketorolac three times a day, depending on insurance coverage, for 6 weeks.

CONCLUSION

We are far away from truly dropless cataract surgery, but current IVAS products provide surgeons with an opportunity to customize their injection approach. At present, IVAS therapy as a standalone intervention may not be sufficient to control postoperative inflammation in certain patient populations. Some risk factors have been identified, but more research is needed to further optimize patient outcomes.

1. Chang A. Analysis of the economic impacts of dropless cataract therapy on Medicare, Medicaid, state governments, and patient costs. October 2015. https://stateofreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CSIE_Dropless_Economic_Study.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2019.

2. Stone JL, Robin AL, Novack GD, Covert DW, Cagle GD. An objective evaluation of eyedrop instillation in patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:732-736.

3. Hennessy AL, Katz J, Covert D, et al. Videotaped evaluation of eyedrop instillation in glaucoma patients with visual impairment or moderate to severe visual field loss. Ophthalmology. 2010;117: 2345-2352.

4. Cate H, Bhattacharya D, Clark A, et al. Patterns of adherence behaviour for patients with glaucoma. Eye. 2013;27: 545-553.

5. Kishore K, Brown JA, Satar JM, et al. Acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery and transzonular intravitreal triamcinolone-moxifloxacin. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(12):1436-1440.

6. Clinical alert: HORV association with intraocular vancomycin. ASCRS website. http://ascrs.org/node/26101. Accessed May 28, 2019.