CASE PRESENTATION

A 63-year-old woman with an unusual history was referred to me for cataract surgery. This patient had begun to undergo cataract surgery a month earlier. She had received a retrobulbar block and been taken to the OR, and the case had been initiated. There had been “a problem with her iris,” and the case was aborted.

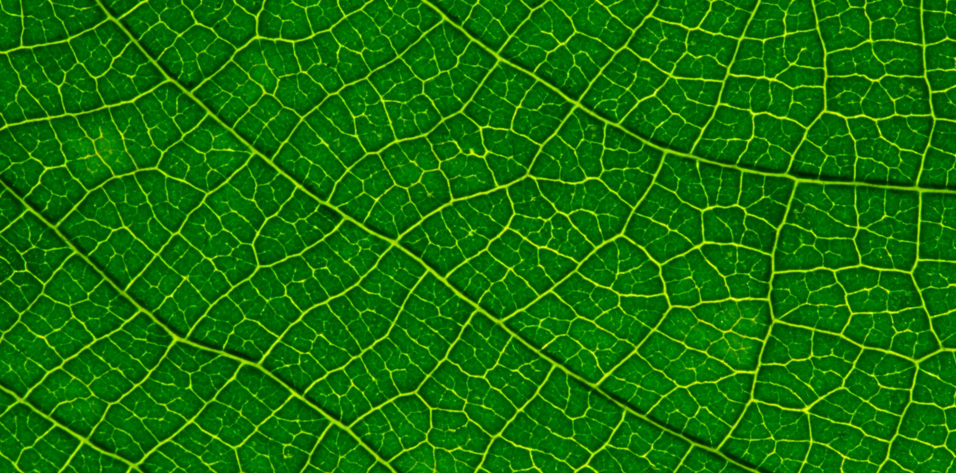

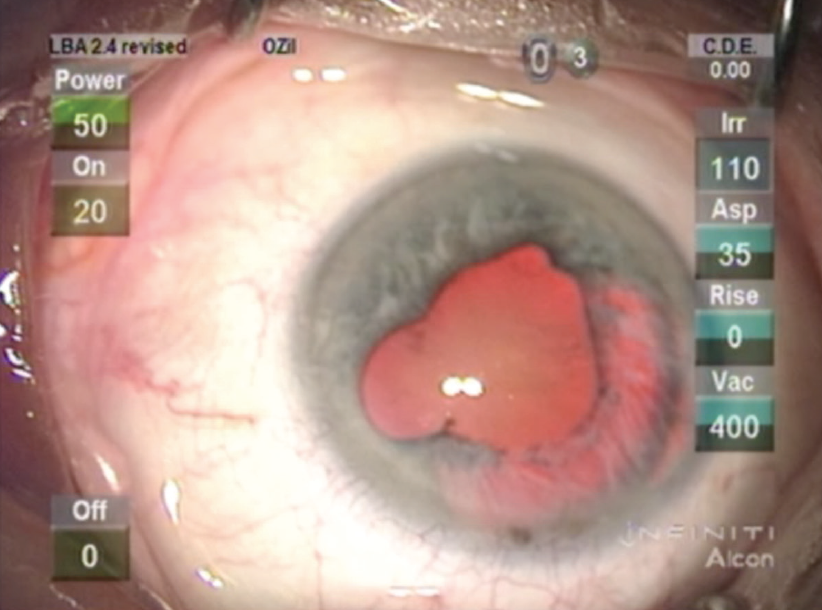

Upon presentation, the cataract remains in the eye, and the patient has completed her postoperative course of medications. She reports that her visual acuity is unchanged since surgery but states that her light sensitivity has increased dramatically (Figure). On close questioning, she recalls a time she tried different medications for a bladder problem.

Figure. The eye’s appearance approximately 1 month after the aborted cataract procedure.

What do you think happened in the original surgery? How would you approach this case? What special precautions, medications, or devices would you plan to employ?

—Case prepared by Lisa Brothers Arbisser, MD

TARA HAHN, MD; AND JEFF PETTEY, MD

The Figure shows pigmentation of the paracentesis, and there is extensive segmental iris atrophy bordering the main wound, indicating repeated iris prolapse during the aborted surgical procedure.

We suspect that, during the original surgery, severe posterior pressure caused both shallowing of the anterior chamber and extensive iris herniation through the paracentesis and main incisions. A potential cause of the posterior pressure is retrobulbar hemorrhage from the retrobulbar block, but we would examine the fundus to rule out choroidal effusions or bleeds.

For the patient’s upcoming cataract procedure, we would not perform a retrobulbar block, and we would reverse anticoagulation preoperatively if possible. We expect that, after gentle mechanical synechiolysis or viscosynechiolysis, extensive iris atrophy and the atonic iris will require the placement of iris hooks or other iris retraction devices.

Throughout the case, we would take care to limit any anterior chamber shallowing by filling the chamber with an OVD prior to removing irrigation. If the patient is experiencing significant visual disability from her reported photophobia or glare, we would consider implanting an artificial iris device.

RICHARD MACKOOL JR, MD

Iris prolapse through the surgical wound at the initial procedure was likely the cause of the temporal iris atrophy. A floppy iris might have been the issue at the initial surgery, but the majority of surgeons can use iris hooks or rings, making iris damage and aborted surgery due to a floppy iris less likely (albeit possible). If the anterior chamber appears shallow at the slit lamp, iris prolapse through the wound during surgery might have been due to a shallow chamber. Posterior pressure with shallowing of the anterior chamber from the retrobulbar block could have occurred as well, with the same consequences, so a deep chamber at the slit lamp would not rule out the possibility of a shallow chamber with iris prolapse during the initial cataract procedure.

I would be prepared to perform a one-port pars plana vitrectomy during the upcoming cataract surgery if the chamber is shallow, and posterior synechiolysis as needed. Iris hooks could be employed if necessary. Given this patient’s glare from iris transillumination defects, I would also plan to implant a CustomFlex Artificial Iris (HumanOptics). Although iridoplasty could improve some of the patient’s symptoms, the temporal iris would remain translucent, and sutures would likely be difficult to place in the moth-eaten temporal tissue.

RICHARD PACKARD, MD, DO, FRCS, FRCOphth

The Figure shows a number of areas of posterior synechiae as well as a large zone of lost iris pigment. I presume that the latter is the cause of the increased glare. This patient has a history of bladder issues, which are probably lower urinary tract symptoms. Alpha-blockers, particularly tamsulosin, have been used for some time to treat lower urinary tract symptoms in women.1 Intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS) and iris prolapse during the initial surgery, resulting in the loss of the iris pigment, might have led to the aborting of surgery.

Another possible reason for the iris tissue’s appearance is that this eye is nanophthalmic with a very shallow anterior chamber and a strong tendency for iris prolapse when an incision is made. It is not possible to tell from the Figure whether this is the case.

What is the solution for this patient? If the problem was caused by IFIS, then the use of intracameral dilating solutions (eg, tropicamide 0.2 mg/mL, phenylephrine hydrochloride 3.1 mg/mL, and lidocaine hydrochloride 10 mg/mL; Mydrane, Théa, not available in the United States) would be required to overcome the alpha-blockade and stabilize the iris. If pharmacologic dilation is insufficient, then either a pupillary expansion ring or iris hooks will be required to keep the iris out of the operative field. This patient will need an iris prosthetic segment to reduce glare.

If the problem is a short eye and shallow chamber, then preoperative administration of 250 mL mannitol 20% will help to shrink the vitreous. Hooks will be required because a ring may be hard to place in a shallow chamber. Injection of an OVD (Healon5, Johnson & Johnson Vision) should deepen the anterior segment. Again, an iris segment will be required.

ELIZABETH YEU, MD

The Figure shows scattered posterior synechiae in half of the iris and diffuse iris transillumination defects involving 5 to 6 clock hours temporally. Iris transillumination defects can occur for a number of reasons perioperatively, including damage to a marginally or poorly dilated pupil; IFIS with iris prolapse; surgical trauma from instrumentation; iris ischemia with a Urrets-Zavalia syndrome–type scenario from an acute hypertensive episode; posterior iris trauma from a large, anteriorly tilted lens; or even postoperative toxic anterior segment syndrome. Urrets-Zavalia syndrome and toxic anterior segment syndrome would result in a more generalized versus sectoral iris atrophy.

It is hard to surmise exactly what led to such diffuse iris atrophy in a sectoral fashion in this case. A combination of factors likely played a role, possibly including a short axial length, a large lens, and excessive positive pressure from the retrobulbar block. The original surgery was clearly aborted early on, prior to the capsulorhexis, so problems must have become evident upon entry into the eye and/or after OVD injection. If the IOP was very high to start with, caused or compounded by posterior pressure from the retrobulbar block, then a rapid decompression of the IOP could have decreased the volume of an already shallow anterior chamber. A very shallow anterior chamber can cause further problems, including anterior rotation of the ciliary body, a choroidal effusion, or, worse, a suprachroidal hemorrhage. This would be accompanied by progressive hardening of the eye and a shallow anterior chamber that could not be deepened with OVD injection. Despite the surgeon’s best efforts, an uncooperative iris combined with potential physical trauma from the abutting anteriorly tilted lens and iris prolapse likely led to significant iris atrophy.

During the upcoming cataract procedure, careful management of the iris will be of the utmost importance to prevent further damage. Preoperative administration of mannitol to minimize vitreous pressure can be immensely helpful in cases such as this. If at all possible, I would not repeat a retrobulbar block but instead would use either a topical approach or, if necessary, general anesthesia. The pupillary opening appears to be between 4 and 5 mm, which is wide enough to permit creation of an adequately sized capsulorhexis and surgery. I would not further manipulate the iris mechanically, for example by stretching, synechiolysis, or placement of a pupillary ring. Iris hooks are contraindicated because they would destroy the fragile temporal iris. The atrophic iris will be prone to prolapse intraoperatively, so all measures should be taken to help keep the tissue as stiff as possible, including use of epi-Shugarcaine (saline solution, lidocaine, and epinephrine), injection of phenylephrine 1% and ketorolac 0.3% (Omidria, Omeros) throughout the case, not overfilling the eye with OVD, and performing gentle hydrodissection. Synechiolysis could be reserved for later in the procedure, after nuclear disassembly was complete and the IOL was well positioned but prior to OVD removal.

Given the patient’s complaints of photophobia, I would consider placing an artificial iris implant or artificial iris IOL implant such as the CustomFlex Artificial Iris to cover the iris defect.

WHAT I DID: LISA BROTHERS ARBISSER, MD

I supposed that the previous ophthalmologist had struggled with posterior pressure and iris prolapse. When I spoke to him, he said that he simply had not been able to manage the case and had told the patient that she needed my help. Although no one had thought to ask her before, questioning revealed that she had briefly taken tamsulosin for urinary frequency a couple of years earlier but that the agent had not been effective. I have no doubt that IFIS contributed to the problems encountered during the first cataract procedure.

On examination, the patient’s UCVA was 20/60 OD, consistent with nuclear sclerosis, and OCT imaging showed no cystoid macular edema. Her photophobia was caused by a loss of iris pigment epithelium for about 4 to 5 clock hours temporally with a resultant transillumination defect and iris atrophy. The cornea was clear, and spotty posterior synechiae were visible. Trace cell and flare were present in the anterior chamber. IOP was 12 mm Hg OD and 14 mm Hg OS. The left eye exhibited a nuclear sclerotic cataract, and UCVA was 20/50.

I initiated treatment of the patient’s low-grade iritis to quiet the right eye. My encounter with this patient took place before the clinical trial or US availability of the CustomFlex Artificial Iris. After thorough informed consent, I submitted a compassionate use application for two aniridia rings (Morcher), devices with which I had several years’ experience. These devices feature black PMMA fins attached to a capsular tension ring. Although still available elsewhere, these implants never made it to formal clinical trials in the United States, and compassionate use has been revoked. I find this unfortunate because the Morcher rings were available at a fraction of the cost of the Artificial Iris.

I performed the cataract procedure using topical anesthesia. Twenty minutes before surgery, the patient received an intravenous bolus of mannitol 0.24 g/kg. Standard preoperative dilation was supplemented with scopolamine for staying power. I created the clear corneal incision superiorly, away from the main area of iris atrophy and the previous incision to ensure that the length of the tunnel would be adequate. After performing an intracameral injection of preservative-free epinephrine (Omidria and phenylephrine were not then available), I instilled Healon GV (Johnson & Johnson Vision) with a soft shell of Viscoat (Alcon) under the endothelium to improve stability and iris control. Upon completion of gentle synechiolysis, I proceeded with standard phacoemulsification and took care not to exit the eye during irrigation or to allow the iris to approach the incision tunnel. Because the iris damage was too extensive to be oversewn, I placed the aniridia rings in the bag after it was cleaned. I was careful to avoid putting stress on the zonules as I rotated the rings into position under the transillumination defect. The one-piece acrylic IOL tucked nicely under the fins of the aniridia rings.

The postoperative course was unremarkable. At the 6-week visit, the eye was quiet off drops, UCVA was 20/20, and the photophobia had completely resolved. With careful precautions to address IFIS, cataract surgery on the patient’s fellow eye was uncomplicated.

WATCH IT NOW

1. Zhang HL, Huang ZG, Qiu Y, et al. Tamsulosin for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Impot Res. 2017;29(4):148-156.