Achieving a watertight wound at the end of cataract surgery helps avoid complications such as hypotony, iris prolapse, and endophthalmitis.1 When stromal hydration is inadequate, the placement of a corneal suture can ensure wound stability. Corneal sutures, however, can also cause astigmatism and foreign body sensation and increase the risk of infection at the time of suture removal. Another option is tissue adhesives, including fibrin and polyethyleneglycol–based products, but their use may be limited by cost and availability.

One of us (A.D.) developed a simple alternative technique that uses blood from adjacent limbal blood vessels to promote cataract wound closure. Blood is rich in clotting factors such as fibrin. Bleeding limbal vessels adjacent to the clear corneal incision made during cataract surgery provide a ready source of these clotting factors. The technique may be used in conjunction with stromal hydration and other closure methods. It takes less than 1 minute to perform, and the learning curve is short, making it useful for surgeons of all skill levels, especially residents.

TECHNIQUE AND TIPS

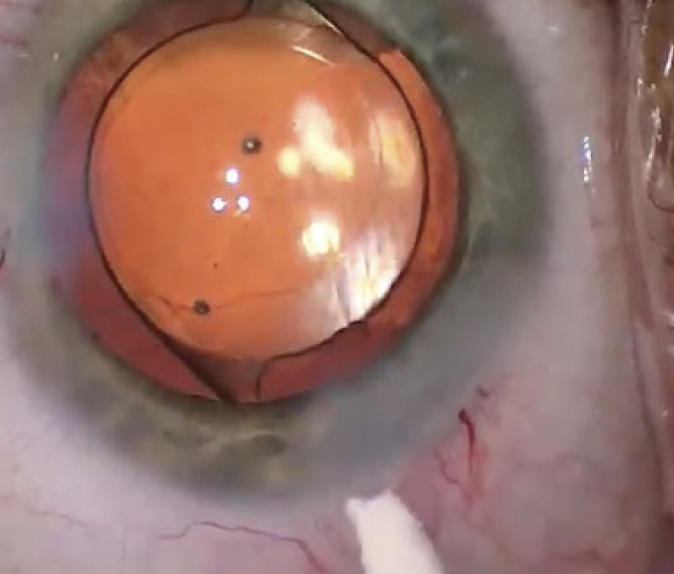

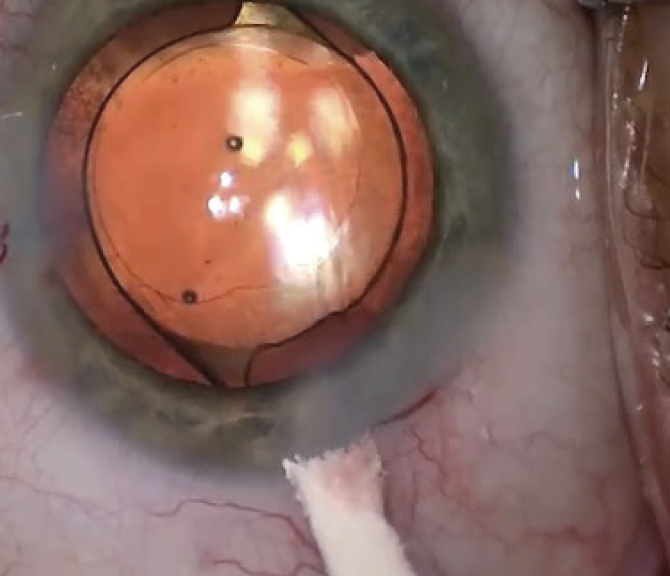

The technique in detail. Proximity to limbal vessels is known to improve wound healing, and blood from these vessels is necessary for success with the technique. The clear corneal incision is therefore initiated at the limbus. At the end of surgery, standard stromal hydration of the roof and corners of the incision is performed with balanced salt solution. Next, a cellulose eye spear is placed at the edge of the incision, opposite the bleeding limbal vessels (Figure 1). Capillary flow draws blood into the incision, introducing clotting factors into the wound (Figure 2). Once the blood is visible in the main wound, the cellulose spear is removed, and the wound is left undisturbed for approximately 30 seconds to allow fibrin to crosslink within the wound tissue. The wound is then checked for stability.

Figure 1. Bleeding limbal vessels are present at one edge of the clear corneal incision.

Figure 2. A cellulose eye spear, placed at the opposite edge of the wound, draws blood into the wound.

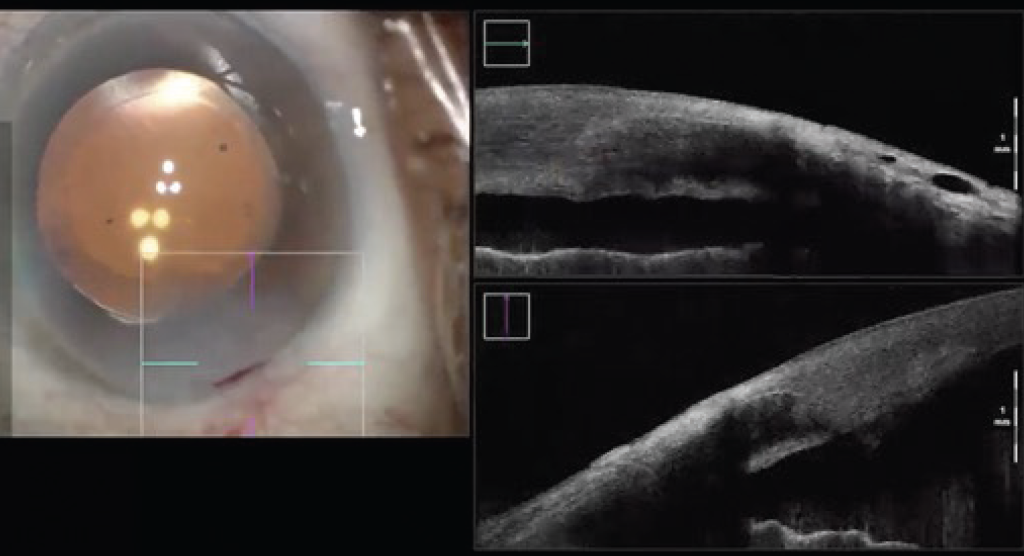

Intraoperative OCT imaging has demonstrated successful wound apposition following the implementation of the technique (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Intraoperative OCT confirms successful wound closure.

Tips. The technique may be used even if no blood is present during wound closure. Vessels that bled during the creation of the main incision might have clotted over during surgery. A paracentesis blade or the blunt cannula of a balanced salt solution syringe may be used to unroof the clots.

A last alternative is to create a new area of bleeding with a paracentesis blade or another sharp instrument. This modification may be useful to surgeons performing MIGS where limbal vessels are avoided to improve the view during intraoperative gonioscopy.

CONCLUSION

The use of a cellulose eye spear to wick blood into the main cataract incision is a simple, inexpensive method for achieving wound stability without the need for additional surgical products.

Blood is a readily available source of fibrin during cataract surgery and naturally enhances tissue stability during wound closure. If the technique combined with stromal hydration provides an inadequate seal, other traditional methods may be employed.

1. Matossian C, Makari S, Potvin R. Cataract surgery and methods of wound closure: a review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:921-928.