Ophthalmologists and primary care optometrists must provide appropriate care for patients with keratoconus (KC) to avoid legal liability.

Ophthalmologists and optometrists have served as expert witnesses in several KC-related malpractice trials. As a lawyer specializing in health care law, I can attest that many more malpractice suits are settled quietly out of court. The doctors involved avoid a trial, but the experience is stressful, expensive, time-consuming, and psychologically draining.

This article describes three types of legal risk that providers should take care to avoid when managing patients with KC.

NO. 1: FAILURE TO DETECT

Eye care providers have a responsibility to screen for and detect ocular disease, including glaucoma, macular degeneration, and corneal ectasia or KC. The detection of KC is within the capabilities of any optometrist or ophthalmologist regardless of the availability of advanced diagnostic technologies. In most states, a slit lamp and keratometer are among the minimum required equipment for an eye care practice; both devices can be used to detect corneal ectasia. Confirmation of KC with advanced topography or tomography is desirable, but the lack of this form of confirmation does not eliminate the requirement to detect risk factors and vision and corneal changes consistent with KC.

In one case I am aware of, a patient in his 30s had longstanding blur and 20/20 BCVA OD and a plano refraction and 20/20 UCVA OS. Past optometrists had overlooked steep keratometry readings on the autokeratometer, asymmetry in keratometry readings between the eyes, and a large mismatch between the autorefraction and manifest refraction. The patient was later diagnosed with KC during a contact lens evaluation. Fortunately, he has mild KC that appears stable. If his outcome had been poor, the first primary care optometrist could have been at risk legally for failing to detect the disease early enough.

NO. 2: FAILURE TO REFER

Once KC has been detected, providers have a duty to treat it appropriately. In the past, patients were managed first with glasses or soft contact lenses and then rigid or scleral lenses. They were referred to a cornea specialist for a keratoplasty procedure only if their vision declined significantly and could not be corrected in any other way. After the FDA approved CXL, the standard of care began evolving away from monitoring to intervention. This demands an earlier referral for treatment, much like with glaucoma.

Standard of care is an elusive concept—it changes over time and can vary by region—but it is essentially a minimum standard for what a doctor in the local area should reasonably know and do to provide appropriate patient care. Courts look at many factors to establish a local standard of care. One that carries significant weight is the existence of a set of formal guidelines from a respected authority. In this context, it is important to be aware that the AAO revised its Preferred Practice Patterns for corneal ectasia in 2018. The guidelines are clear about the urgency of frequent follow-up to monitor patients for potential disease progression and the importance of early referral for CXL to halt KC progression and preserve visual acuity (see Key Points From the AAO’s Preferred Practice Patterns on Ectasia).1 Providers may find it hard to argue that they are upholding the standard of care if they ignore these guidelines and allow patients to continue experiencing disease progression without a referral.

Key Points from the AAO Preferred Practice Patterns on Ectasia

- Patients with unstable refractions should be evaluated for evidence of corneal ectasia. Vision testing alone is not sufficient. BCVA may not completely characterize visual function in these patients.

- It is ideal to identify disease progression before it affects vision. Waiting for additional loss of BCVA should be avoided.

- Once disease progression is observed, early detection and prompt treatment with CXL can reduce or stop keratoconus progression and preserve good visual acuity with eyeglasses and/or contact lenses. Glasses, contact lenses (including scleral lenses), and intrastromal corneal ring segments do not alter disease progression.

- More frequent follow-up (ie, every 3 to 6 months or more frequently for younger patients) to look for progression is warranted.

- Patients with corneal ectasia should be referred promptly to an ophthalmologist with expertise in managing corneal disorders if any of the following occurs:

- Vision loss;

- Loss of functional vision;

- Acute hydrops;

- Disease progression; and

- Onset at a young age.

Source: Garcia-Ferrer FJ, Akpek EK, Amescua G, et al; American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea and External Disease Panel. Corneal Ectasia Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):170-215.

If a patient refuses to schedule a corneal consultation when referred or to undergo the recommended treatment, providers may want to document it by having the patient sign a refusal to treat or refusal to refer form (see examples at www.drkatiespear.com/forms). I also recommend instituting a regular process for following up with patients who have been diagnosed with a sight-threatening disease and have not shown up for appointments. These steps can help avoid scenarios in which a patient later claims they were not made aware of the severity of their condition or the urgency of treatment.

The policy at my practice is to call patients with certain diagnoses (eg, age-related macular degeneration, KC) three times and then send a certified letter reiterating our concern about disease progression. Having a standard procedure not only prevents patients from falling through the cracks but also acts as documentation that the doctor made a good faith effort to provide at-risk patients with the care they need.

NO. 3: IMPROPER REFERRAL

Once a referral to a specialist is made, primary care providers typically do not have any liability for the outcome of a surgical procedure. The surgeon or CXL physician bears responsibility for performing the procedure according to the standard of care. Failure to execute due diligence in referring patients to providers who perform appropriate treatment could result in malpractice exposure for the referring doctor. For example, referring patients with diabetic retinopathy to a retina specialist who performs panretinal photocoagulation but not antivascular endothelial growth factor injections could be considered improper.

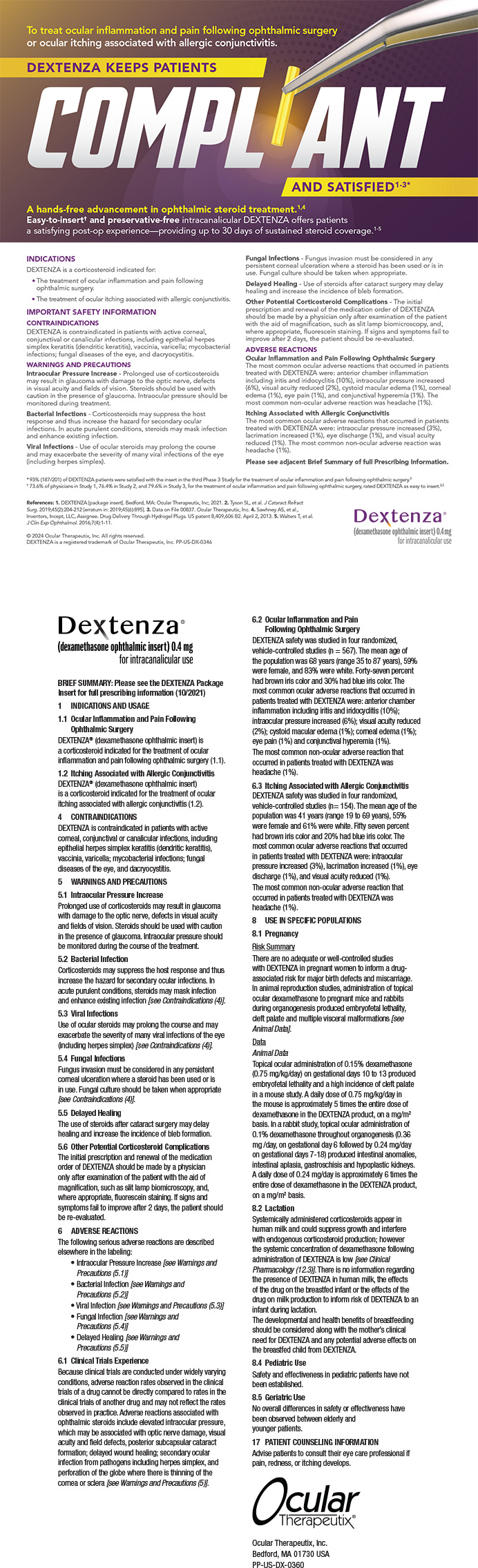

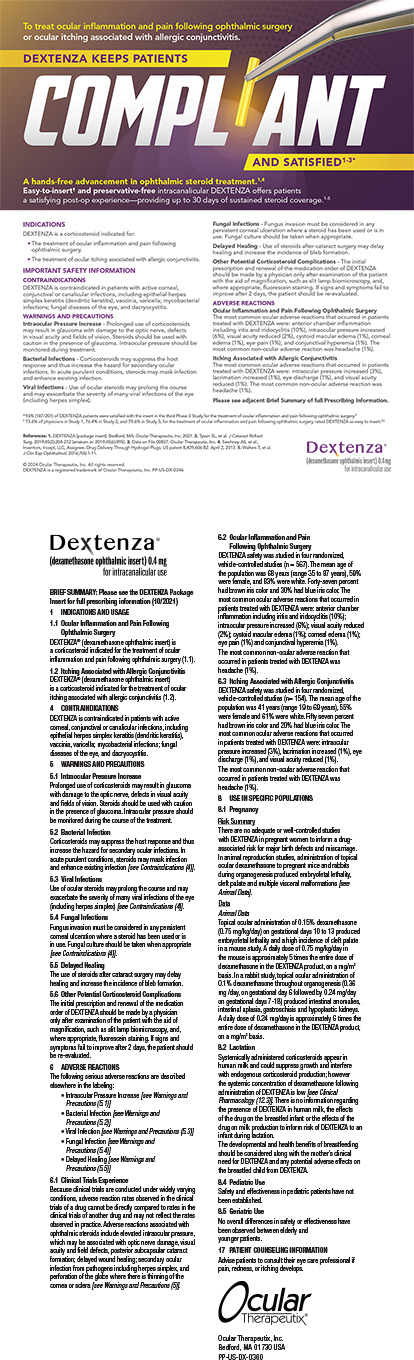

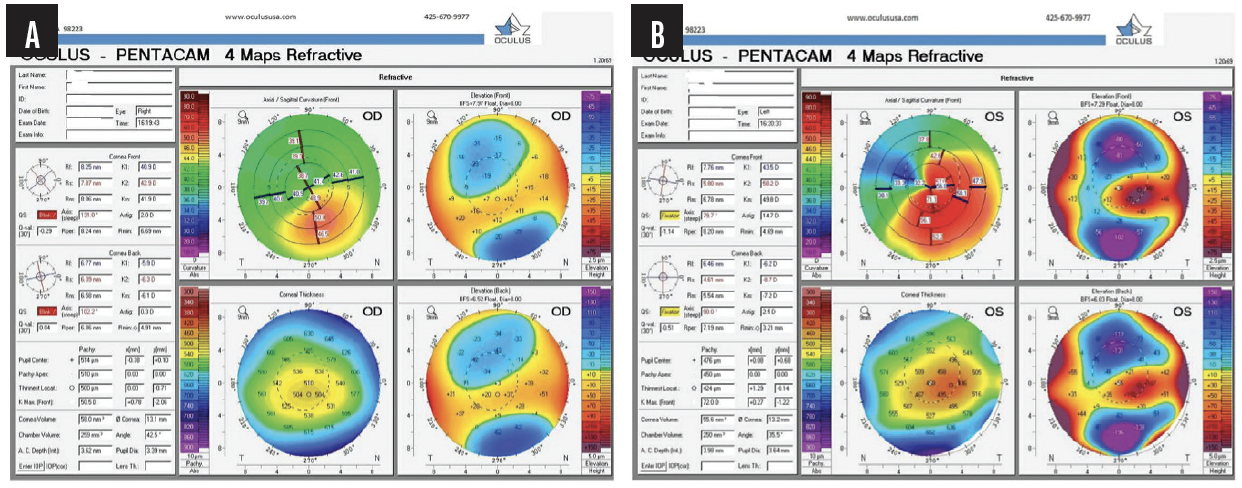

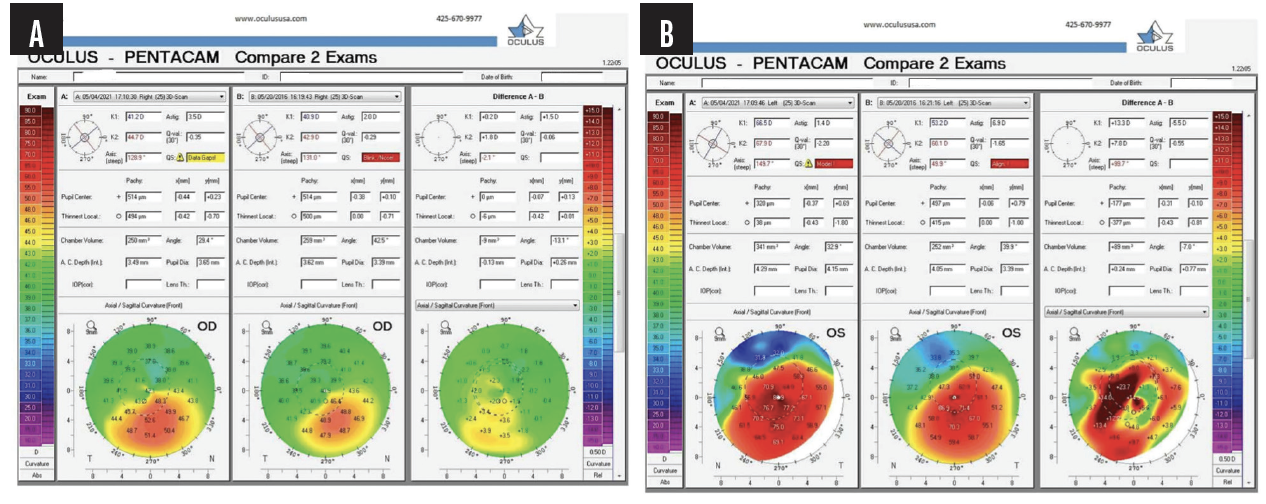

In a case that went to trial and was described to me by Eric Conley, OD, MJ, FAAO, a 19-year-old Hispanic man sought an update to his glasses prescription after experiencing a decrease in vision in both eyes. Based on keratometry, a slit-lamp examination, and corneal imaging, he was diagnosed with progressive KC in both eyes (Figure 1) and referred to a surgeon for epithelium-on (epi-on) CXL with an unapproved system and compounded riboflavin. (The only FDA-approved CXL treatment for progressive keratoconus is iLink with the KXL system and either Photrexa [riboflavin 5’-phosphate ophthalmic solution] or Photrexa Viscous [riboflavin 5’-phosphate in 20% dextran ophthalmic solution] solution [all from Glaukos]. This is the only drug-device combination that can be reimbursed by insurers as a covered procedure.) The surgeon misrepresented the treatment as an off-label use and stated that the procedure would not be covered by insurance without disclosing the availability of a covered and FDA-approved CXL procedure. The patient paid $6,500 out of pocket for the procedure. During the subsequent 5 years, disease progression was evident in both eyes (Figures 2 and 3). The patient’s BCVA was 20/80 OS due to significant corneal scarring and haze.

Figure 1. Baseline tomography of the right eye demonstrates early KC (A). Baseline tomography of the left eye demonstrates moderate KC (B).

Figure 2. Tomography after failed epi-on CXL demonstrates KC progression in the right (A) and left (B) eyes.

Figure 3. Tomography progression maps after failed epi-on CXL demonstrate KC progression in the right (A) and left (B) eyes.

Not only is performing CXL with the FDA-approved technology the right thing to do, but it also protects the referring doctor. If a patient has an outcome like the one described after being sent to a doctor who performs CXL with unapproved devices and medications (outside of a registered clinical trial that has both Investigational New Drug Application approval from the FDA and Institutional Review Board oversight), the cornea specialist may be in legal jeopardy. The FDA has sent warning letters to surgeons who use unapproved drugs and devices. The referring clinician may also be found negligent. Due diligence before making a referral includes reviewing the practice’s website, talking to the cornea specialist, and, ideally, visiting the practice or watching a procedure to better understand what patients can expect. A directory of physicians performing iLink CXL may be found at www.livingwithkeratoconus.com/find-an-expert.

CONCLUSION

Eye care providers are fortunate that the options for treating KC have expanded and that CXL can slow or halt progression of ectatic disease. As standards for KC care evolve, it is important for providers to stay abreast of scientific developments and guidelines to protect themselves and their practices from legal exposure.

1. Garcia-Ferrer FJ, Akpek EK, Amescua G, et al; American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea and External Disease Panel. Corneal Ectasia Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):P170-P215.