As a student, when I thought about academic medicine, I thought of towering medical plazas with well-dressed physicians in sharp-looking white coats walking the premises. An aura of prestige emphasized the Hippocratic oath. This was where true medicine happened, where students became doctors, and where breakthroughs in research occurred every day. I thought these institutions stood above the controversies of modern medicine.

The reality is that academic medicine is a business. Universities are revenue-focused companies that rely more than ever on their reputations to bring in endowments, donor contributions, and research funding. Reputation is truly everything for these institutions, and, at times, it can make them vulnerable to controversies and taboos. One controversy that is now making the front pages of newspapers across the country is gender disparity in the medical field.

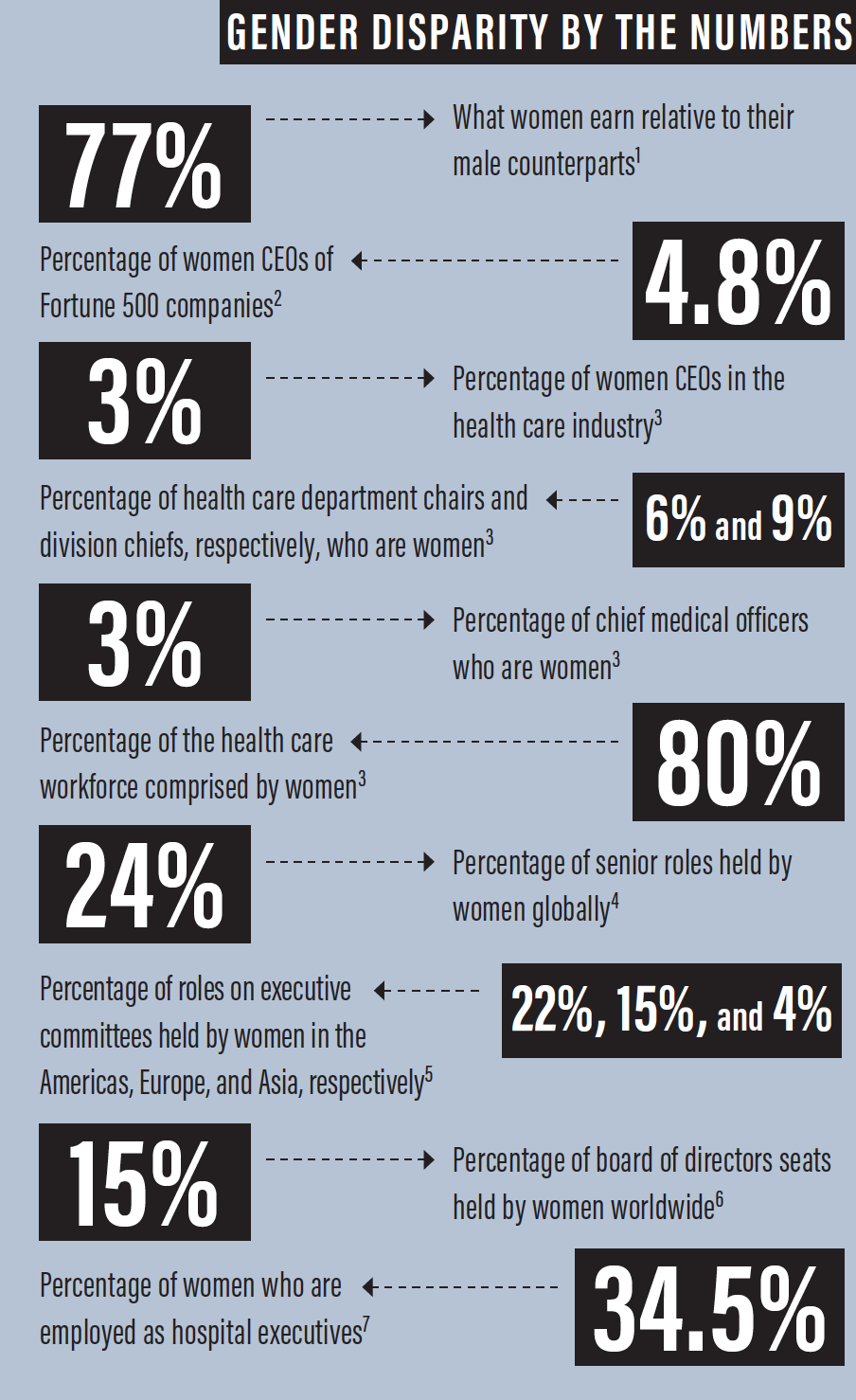

Women account for half of all medical school graduates in the United States and more than half of incoming ophthalmology residents.1 This is a huge swing from several decades ago and a testament to the growing diversity in medicine. Despite this shift, however, women continue to lag behind men in their representation in the upper ranks of academic medicine and in leadership roles, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.1 This disparity is even greater for women of color, who represent 11% of full-time faculty and hold only 3% of department chairs.

Three key reasons for gender disparity discussed in the literature are reinforced stereotypes, social exclusion of female colleagues, and unprofessional behavior. Unfortunately, as a junior female faculty member in academics, I have seen them all.

PROMOTION IN THE WORKPLACE

Several studies have looked into why women either are not promoted or leave academic medicine. One study followed 1,273 faculty members at more than 20 US medical schools for 17 years to identify predictors of advancement, retention, and leadership for women faculty members.2 It found that women were less likely than men to achieve the rank of professor or to remain in academic careers. Male faculty members were more likely to hold senior leadership positions after adjusting for publications.

Women are also paid less than men in academic settings, even when covariates such as part-time work and publications are accounted for. I once took a leadership role and found out 6 months later that my paycheck was 50% less than my male predecessor, despite an acknowledgment from my superior that I was doing more work. I debated whether and how I should approach the issue. My male colleagues insisted that I renegotiate my salary. Discrepancy in salary negotiation is a common issue even outside of health care, as women continue to be paid less than men.

In another example, an extremely talented female ophthalmologist was passed over for a leadership role despite having a more impressive résumé and national reputation than her male counterparts. When she asked her chair for the reasoning behind the decision, she was informed that it was thought she would be “too busy to focus” because she had young children. She left academics the following year for private practice—an excellent example of how treatment in the academic workplace led to a regrettable loss of talent for academic medicine.

REINFORCED STEREOTYPES

The phrase mommy-tracked refers to the stereotype that a woman will one day decide to throw away all of her training and education to stay at home or work part-time.

Take maternity leave: There are human resources rules governing what you can and cannot say to someone who is about to take a leave of absence in accordance with the Family Medical Leave Act. Despite this, it is incredible the comments some people will make.

As I was planning my own maternity leave, 5 months in advance, I was told by leadership that my requests for additional patients would not be honored because I was “going on maternity leave anyway.” They also asked several times if I was coming back full-time after my leave. There was never any discussion about my coming back on a part-time basis. Instead of seeing more patients as I requested, my schedule was gently changed to allow technician support for other faculty members, despite my leave being planned months in advance. How can one “lean in” when leadership is already leaning you out?

Sadly, much of this stereotyping comes from female colleagues and administrators. Prior generations had to prove their ability to work on the same level as male colleagues by coming back after as little as 2 weeks of leave. They tell their stories as though they are badges of honor, and they scoff at a younger generation taking a full 3 months. In response, I think: If a male faculty member had a health crisis, would he feel just as obligated to return to work before fully recovering? If our female mentors aren’t supportive, how can we ask for support from our male counterparts?

Administrators are likely the harshest. The differences in treatment between male and female physicians are ever apparent. Administrators feel comfortable calling me by my first name, while younger male colleagues are often called Dr. Last Name. I have emails that were sent to me and another female faculty member with the greeting, “Ladies, …”. Complaints from a female faculty member about safety and efficiency in the OR are treated differently from those made by male complaints at our surgery center, to the point that we raised this concern at faculty meetings.

BEHAVIORS IN THE WORKPLACE

Unfortunately, ophthalmology is no stranger to the front page of the news when it comes to unprofessional behavior in the workplace. Relationships in any workplace environment have the risk of turning unprofessional, and medicine is notorious for a don’t ask, don’t tell attitude.

Certain behaviors and comments that are observed in medicine would never be tolerated in a traditional workplace. This is likely due to the hierarchical structure of medicine: from chair, to professor, down to a student or PhD who may be the most vulnerable. Perhaps junior faculty members are naïve regarding the rights they have as employees. They might also be fearful of long-term implications in networking or job searches if they bring up complaints of unprofessional behavior. Sadly, though, it is likely that the biggest barrier is a lack of trust in the institution to act on a complaint in a way that doesn’t aim to protect its own reputation and that of the instigator.

1. Khan H, Moosajee M. Facing up to gender inequality in ophthalmology and vision science. Eye (Lond). 2018;32:1421-1422.

2. Zarya V. The share of female CEOs in the Fortune 500 dropped by 25% in 2018. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2018/05/21/women-fortune-500-2018/. Accessed

September 18, 2019.

3. Rotenstein LS. Fixing the gender imbalance in health care leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/10/fixing-the-gender-imbalance-in-healthcare-leadership. Accessed September 19, 2019

4. Thornton G. Women in Business: Beyond Policy to Progress. https://www.grantthornton.global/en/insights/articles/women-in-business-2018-report-page/.

Accessed September 18, 2019

5. 20-first’s 2018 global gender balance scorecard. 20-first. https://20-first.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ScoreCard-GlobalGenderBalanace.jpg. Accessed

September 18, 2019

6. Women in the boardroom: A global perspective. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/risk/articles/women-in-the-boardroom5th-edition.html.

Accessed September 18, 2019.

7. Gender inequality still plagues the health care industry. Women are fed up. Stat News. https://www.statnews.com/2018/08/01/gender-inequality-health-careleadership-women/. Accessed September 18, 2019.

One example I witnessed was a resident who tolerated inappropriate comments from an attending throughout her training. At the time, she never thought about it as a violation of human resources rules, but rather with a “boys will be boys” mentality. Now, further along in her career, she has witnessed others experiencing similar situations with that same attending, but she remains quiet because complaints in the past have not been acknowledged by leadership. She actively avoids activities that would put her in a direct working relationship with that person.

THE FUTURE

The good news is that these problems are no longer secrets. Active work is being performed to understand the gender issues in academic medicine. Institutional actions to address these disparities include both initial appointment and annual salary equity reviews, training of senior faculty and administrators to understand implicit bias, and training of women faculty in negotiating skills.3

Additionally, there is a trend among the younger generation, regardless of gender, to prefer a better work-life balance.

Most important, regardless of the hierarchy of the academic center, issues around abuse of power or prevention of promotion must be addressed swiftly, in a manner similar to or even better than our peers in non–health care fields. Only then can those pristine white coats and towering medical pillars truly stand for what academic medicine should: opportunity, prestige, and, most important, an opportunity to learn how to act correctly in the future.

1. Lautenberger D, Moses A, Castillo-Page L. An overview of women full-time medical school faculty of color. Association of American Medical Colleges: analysis in brief. 2016;16(4).

2. Carr, PL, Gunn C, Raj A, Kaplan, SE, Freund KM. Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: How institutions are addressing gender disparities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):374-381.

3. Freund KM, Raj A, Kaplan SE, et al. Inequities in academic compensation by gender: a follow-up to the National Faculty Survey Cohort Study. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1068-1073.