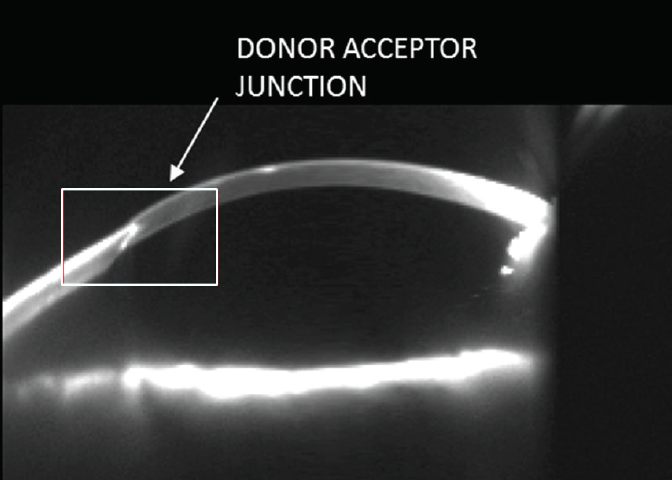

Corneal blindness affects millions of people worldwide. It can result from a number of causes, including trauma, infection, and inflammatory or congenital disorders of the eye. Subsequent visual impairment can be resolved by transplantation of a donor cornea. With 1.5 million patients added to waiting lists every year, however, there are not enough donor corneas to meet the demand. Moreover, no geometric or human leukocyte antigen matching of donor corneas is currently performed, and postoperative immunosuppression and refraction are almost always required to achieve good visual outcomes (Figure 1). Another problem is that artificial corneas such as the Boston Keratoprosthesis and AlphaCor (Addition Technology) are made of plastics that do not bio-integrate, making them prone to rejection or extrusion. For this reason, these devices are reserved for extremely high-risk cases.

Figure 1. Scheimpflug photography of this cornea shows a mismatched donor-host junction. At present, no matching of donor and host corneas is performed, leading to postoperative problems.

3D printing is a manufacturing process that builds layers to create a 3D solid object from a digital model. The cornea is a relatively homogeneous tissue composed of regularly arranged and tightly packed collagen fibers. It is devoid of blood vessels and easily accessible. These qualities make it an ideal candidate for tissue engineering using 3D printing. 3D-printed corneas made from biomimetic materials to precisely match a patient’s corneal geometry could theoretically eradicate the need for postoperative immunosuppression and refraction.

HOW ARE THESE CORNEAS MADE?

We are currently collaborating on a project with Eleonora Ferraris, PhD, and PhD Candidate Rory Gibson from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Leuven, Belgium. We have modified an Aerosol Jet Printer (AJP, Optomec) so that it can print with recombinant human collagen type III. The collagen is aerosolized and guided through a nozzle to print at very high resolution (5–10 µm with a layer thickness of 1–2 µm). The high resolution means that several hours are required to print a single sample. Further technological refinement could allow faster manufacturing.

Other groups are also exploring 3D printing as a solution to corneal blindness, but they have used commercially available extrusion-based or modified ink-jet printers that have fairly low resolution in comparison (50–100 µm).

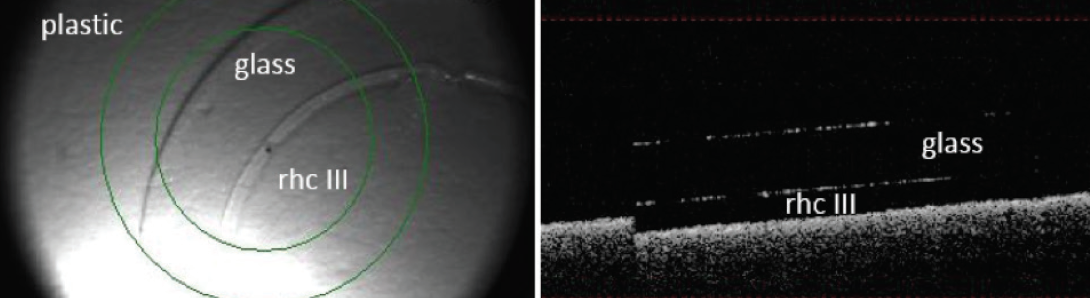

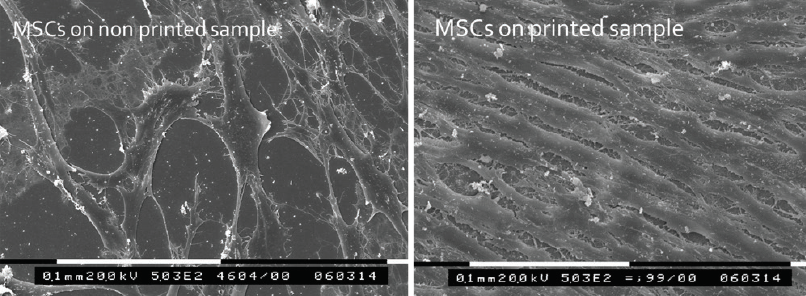

We are crosslinking the AJP-printed biocorneas (Figure 2) and testing them for collagen integrity, optical transparency, strength, rigidity, and geometry. To further test their biocompatibility, we have seeded the printed biocorneas with human corneal mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The MSCs showed cellular alignment and penetration into the body of the scaffold, mimicking the natural situation in the human cornea (Figure 3).1

Figure 2. En-face image (left) shows 3D-printed recombinant human collagen type III (rhc III) on a glass coverslip. OCT (right) shows a cross-section of the cornea. This sample has 10 layers and a mean thickness of 33.4 ±10.7 μm.

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy of nonprinted (left) and 3D-printed (right) recombinant human collagen samples seeded with corneal MSCs. Cellular alignment can be seen along the print pattern but is absent in the nonprinted control samples.

CHALLENGES

The main challenge in this project thus far has been optimizing the printing process. Because the AJP was previously used to print only nonbiologic inks (eg, metal conduits on computer parts), we had to adapt the device for use with biologic material, as noted earlier. A lot of modifications were required before we could print samples with certainty of reproducibility—a necessity for biocompatibility testing.

Before this technology can be brought to the clinic, we need to increase the dimensions of the printed samples, perform mechanical testing for rigidity, and determine whether these 3D-printed collagen constructs can undergo suturing without tearing. We have determined the tissue’s biocompatibility in vitro, but we must demonstrate the implant’s safety and feasibility in an animal model of corneal transplantation before a biocornea may be implemented in a human patient.

THE FUTURE

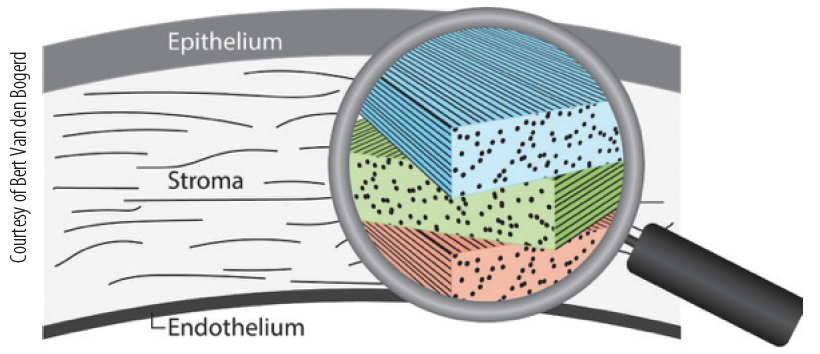

One of the main advantages of using 3D printing is that collagen can be deposited in a layered fashion, allowing us to simulate the constitution of collagen fibrils in a native corneal stroma (Figure 4). Once 3D-printed biocorneas can become available in clinics, there is the potential to customize the tissue to each specific patient.

Figure 4. The corneal stroma consists of layers of collagen fibrils that are stacked, every layer with a slightly different orientation from that of the adjacent layers, which is the main reason for the strength and transparency of the cornea.

Our hope is that 3D-printed biocorneas reach the clinic within the next decade. Depending on the success of initial clinical trials, the tissue could then become commercially available for use worldwide.