I was the first US doctor to be granted expanded access to cenegermin-bkbj ophthalmic solution 0.002% (20 µg/mL; Oxervate, Dompé) before the drug became commercially available in this country. Sometimes referred to as compassionate use, expanded access is a pathway that makes therapeutic drugs that have not yet been approved by the FDA available to a seriously ill patient when no other treatments are effective (see Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Compassionate Use). These agents are called investigational drugs and are usually available only to participants of a clinical trial; their use outside of this setting is extremely limited. This article details my experience with the compassionate use of a drug for a pediatric patient with neurotrophic keratitis.

Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Compassionate Use

Compassionate use has become easier to obtain in recent years. In 2015, in response to criticism that the obtainment of expanded access was too slow and cumbersome, the FDA streamlined the application process. The FDA approves nearly 99% of compassionate use applications.1 Practitioners must remember, however, that only a fraction of the drugs and devices that are investigated through clinical trials subsequently come to market, often because of safety concerns. It is best to weigh the pros and cons of treating a patient with an unapproved product before applying for compassionate use.

It is also advisable to consider the goals of the company. For example, the primary goal of a pharmaceutical company is to navigate a drug through clinical trials as quickly as possible for the good of the company and the general population. Compassionate use requests can sometimes be considered a distraction from the bigger picture. Reasons include the following:

- Drugs that are complex to manufacture may be produced in quantities that are sufficient only for the FDA trials;

- Patients who wish to apply for compassionate use are often sicker than those enrolled in the clinical trials and therefore may have a higher risk of a bad outcome;

- Negative publicity associated with a bad outcome could adversely affect a drug’s chances of approval; and

- A patient may not wish to enter a clinical trial and risk receiving a placebo if they could obtain the desired medication through a compassionate use request.

1. Jarow JP, Lemery S, Bugin K, Khozin S, Moscicki R. Expanded access of investigational drugs: the experience of the Center of Drug Evaluation and Research over a 10-year period. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2016;50:705-709.

BLINDING NEUROTROPHIC KERATITIS

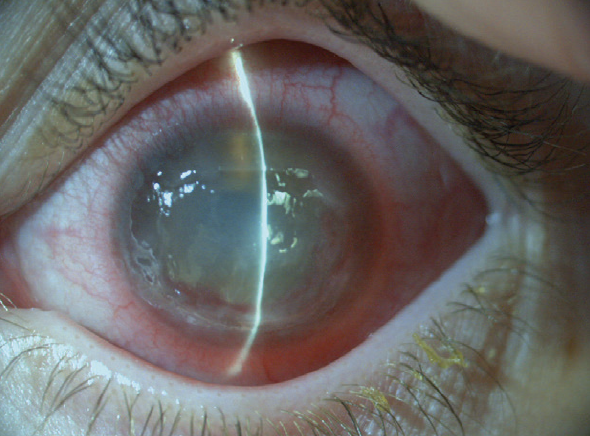

A 12-year-old girl had a history of a few transient episodes of redness in her left eye when she was younger that had cleared spontaneously. The patient presented in 2018 with more persistent redness and severe vision loss associated with neurotrophic keratitis and a corneal ulcer. The underlying cause was presumed to be reactivation of previously dormant herpes simplex keratitis.

On examination, the patient’s BCVA was 20/15 OD and hand motions OS. A 4.5 x 5.5-mm central epithelial defect was present in the left eye. The defect was a shallow saucer-shaped depression with rolled epithelial edges that implied chronicity. Greyish anterior stromal haze was observed. The conjunctival vessels of the left eye were hyperemic with perilimbal flush.

The left cornea was completely anesthetic, so the patient was not experiencing pain or discomfort. Testing with a Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometer demonstrated normal corneal sensation in the right eye and a complete absence of sensation in the cornea of the left eye.

The deep tendon reflexes were intact. Both eyes were moist, and Schirmer testing demonstrated greater than 25 mm of wetting by 5 minutes. The eyelids were normal and able to close completely. The anterior chamber of the left eye showed modest flare but no visible cellular reaction.

The epithelial ulcer did not appear to be actively infected. Cultures were negative for herpes simplex virus, bacteria, and fungus. The patient was treated empirically for 10 days with topical antibiotics combined with oral valacyclovir to cover occult infectious possibilities.

The ulcer progressed during the next 2 months despite all therapeutic attempts to heal it (Figure 1). Conventional treatment, including preservative-free ocular lubricants, autologous serum, a therapeutic bandage contact lens, cryopreserved and dehydrated amniotic membrane transplantation, and extended pressure patch occlusion therapy, all failed.

Figure 1. Neurotrophic keratitis.

A REQUEST FOR EXPANDED ACCESS

Permanent blindness in the patient’s left eye and loss of the eye were real possibilities. I recalled hearing that promising results with cenegermin as a treatment for neurotrophic keratitis were being reported in Europe. I contacted Dompé to request compassionate use of the drug and petitioned the FDA for expanded access for my patient. The request included detailed medical information about the patient, an explanation of why the request was necessary, a proposed plan of treatment, and the patient’s signed consent.

Dompé agreed to provide the medication at no cost. While we waited for it to arrive, a temporary suture tarsorrhaphy was performed to protect and stabilize the globe. The patient continued a regimen of oral valacyclovir, doxycycline, and vitamin C. Four weeks later, the cenegermin arrived. The patient was instructed to instill the solution six times per day for the next 8 weeks.

OUTCOME

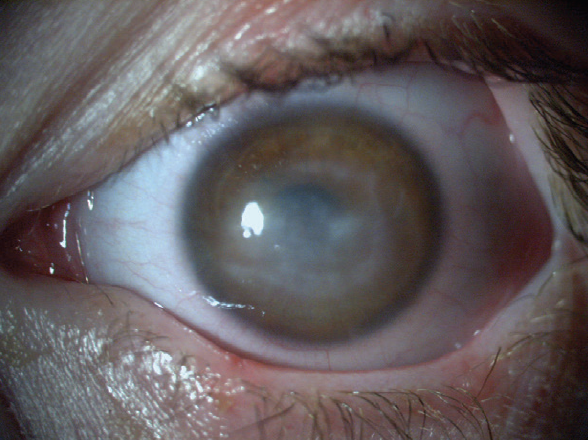

With the combination of cenegermin therapy and tarsorrhaphy, the corneal ulcer finally began to heal. The tarsorrhaphy was removed, and the epithelium remained intact and smooth (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Immediately after treatment with cenegermin, the patient’s BCVA was hand motions, but the corneal epithelium was intact.

Figure 3. Two years after treatment, the patient’s BCVA was 20/30.

The patient currently enjoys good vision in the left eye and has not experienced a recurrence of the hyperemia, neurotrophic keratitis, or corneal ulcer. Not only did Dompé help this patient, but the success of treatment in this case helped the company obtain FDA approval for cenegermin, including for the treatment of pediatric patients.