I enjoy a challenge. My favorite surgical consultations tend not to have straightforward answers. The scenario typically involves a patient who is seeking refractive surgery and doesn’t fit nicely into a specific category. It could be a 35-year-old with 5.00 D of hyperopia who has become intolerant of contact lenses and is seeking LASIK, or it could be a 45-year-old person with -8.00 D of myopia, 3.00 D of astigmatism, thin corneas, and presbyopia. My experience, my skills, and the tools I have at my disposal inform my recommendations.

I believe that magic happens at the intersection of art and science. That intersection is where I enjoy operating, and it is exactly where I found myself when a friend and colleague requested a refractive surgery consultation for himself about a year ago (see Honoring My Refractive Needs).

Honoring My Refractive Needs

By Michael K. Smith, OD

I began wearing glasses in kindergarten after I underwent an eye exam at my teacher’s recommendation. When I was 13 years old, I convinced my parents and optometrist that I was responsible enough to wear contact lenses. My optometrist warned me that I was not an ideal candidate for soft lenses and that he had never attempted to fit a prescription with such high astigmatism, but we decided to proceed. Once the lenses arrived at his office and I was able to get them on my eyes, I stood, walked to the window, and looked out. I could see better than ever. On the drive home, I told my mom I wanted to be an optometrist.

Contact lens wear improved several aspects of my life, and I wore contact lenses successfully for more than 3 decades. What I did not know until I was in optometry school, however, was that I had significant mixed astigmatism, even when wearing my contact lenses. I had adapted well to it, but then I began to develop presbyopia.

I had maxed out the capabilities of contact lenses, and I did not want to resume wearing glasses full time. My vision was poor at both distance and near, and it fluctuated significantly throughout the day. I was also experiencing eye strain and headache. My wife, also an optometrist, told me it was ridiculous for an optometrist to allow himself to have such vision problems.

I decided to see if a surgical procedure could help me. I knew that LASIK and PRK were contraindicated for me because of my extreme astigmatism, but I thought refractive lens exchange could help me now that I was losing accommodative amplitude. I contacted my friend and colleague Gary Wörtz, MD, for advice because I consider him to be a progressive surgeon who is knowledgeable about the products available.

During the preoperative examination, Dr. Wörtz informed me that no IOL would correct my astigmatism completely and that my corneas were too thin to allow correction of any residual astigmatism with corneal surgery. We discussed some outside-the-box potential options, but Dr. Wörtz wanted to do further research. Not long after, he contacted me and explained that he had found an IOL that could fully correct my astigmatism. The IOL, however, was not approved by the FDA. He told me about the FDA’s expanded access program and began the process of obtaining access from the FDA and acquiring the lens from overseas.

Luckily, the request for expanded access in my case was approved. I decided to go with a monovision correction. The surgeries and my recovery were flawless. Now, I can function without correction at all distances and for all tasks for the first time in my life. It has been life-changing. I am grateful that this technology exists and that we were able to gain access to it.

CASE PRESENTATION

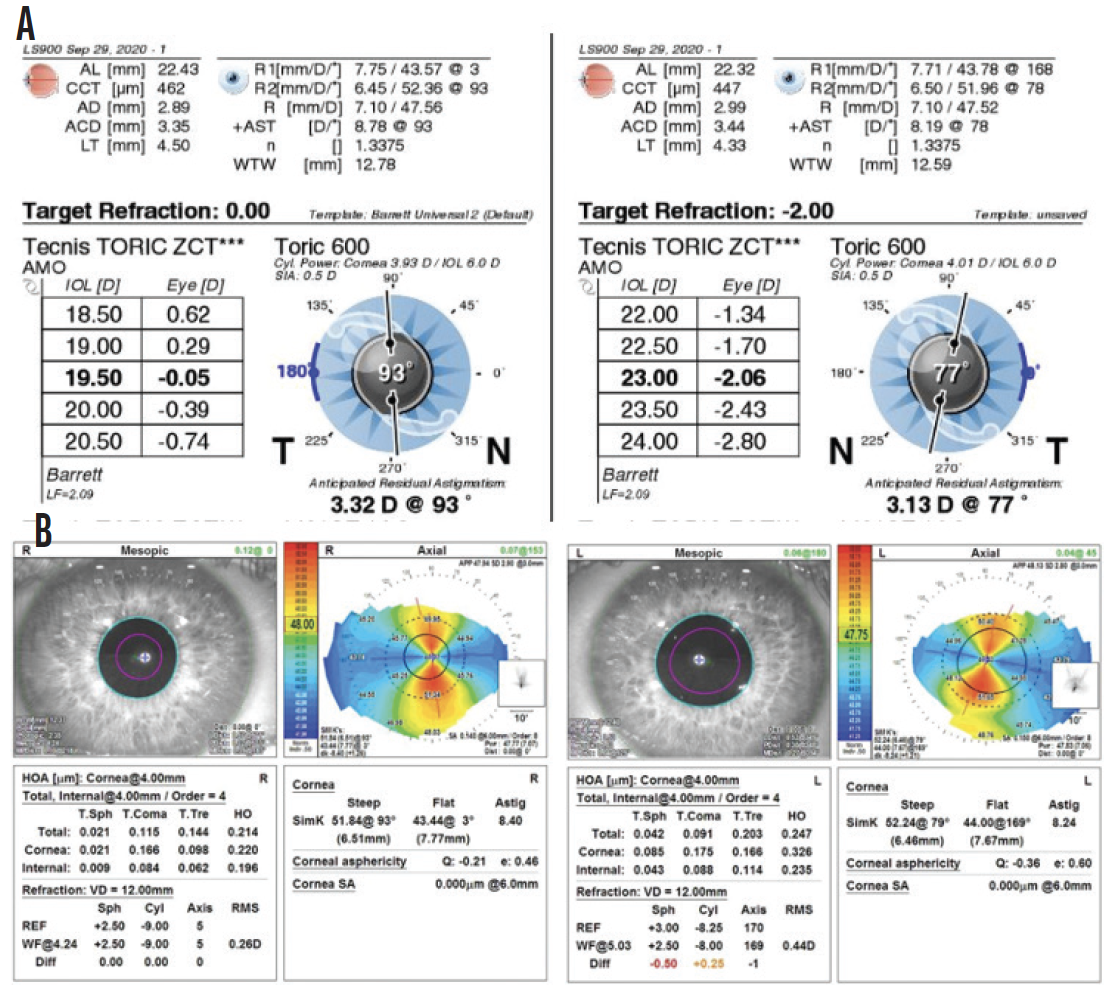

As an eye doctor himself, the 45-year-old patient—Michael K. Smith, OD—was able to let me know in advance that his situation was atypical. He presented with a strong desire to undergo refractive surgery. His BCVA was +2.50 -9.00 x 005º = 20/25 OD and +3.00 -8.25 x 170º = 20/30 OS. Pachymetry readings were 462 µm OD and 447 µm OS, and ectasia markers were unreliable because of extreme astigmatism. He was also losing accommodative amplitude.

Dr. Smith had recently become contact lens intolerant and had poor functionality in glasses due to the aberrations from the strong prescription for high astigmatism (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dr. Smith’s preoperative optical biometry (A) and topography measurements (B).

PHONE A FRIEND

I am blessed to have access to many bright ophthalmic surgeons through my membership in the CEDARS/ASPENS society. I shared the case presentation with the group and asked how they would proceed. Tal Raviv, MD, pointed me to iols.eu, a website that lists the IOLs available in Europe.

Upon browsing the website, I learned that VSY Biotechnology makes an extended-range toric IOL (Acriva BB T UDM 611) that can correct up to 10.00 D of astigmatism. I instantly decided the technology was worth considering. After discussing it with Dr. Smith, we agreed that a refractive lens exchange to correct his hyperopia and astigmatism was our best option.

GAINING ACCESS

The next step was navigating the FDA’s expanded access program, which is also known as the compassionate use program. The process was relatively straightforward, and the FDA’s expanded access team was easy to work with. It took about 6 months to complete the process.

Certain criteria must be met to gain access to a non–FDA-approved device. First, the company must agree to provide the device if the FDA grants access. Second, if the device is currently in use in a US clinical study with an investigational device exemption, the patient must be enrolled in the trial, which can be difficult to accomplish. If there is no ongoing trial, which was the case with the Acriva, the next step is to answer basic questions about why expanded access is being sought, why other approved procedures and devices are not sufficient, and how the requested device would work. An independent second opinion about the case from an ophthalmologist outside of the applicant’s practice must also be obtained. Additionally, an informed consent document tailored to the case must be submitted, and approval from an Institutional Review Board must be obtained. Sterling IRB helped us navigate the process.

IOL POWER CALCULATIONS

I decided to use a monovision strategy with a plano refractive target for Dr. Smith’s right eye and a target of -2.00 D for his left.

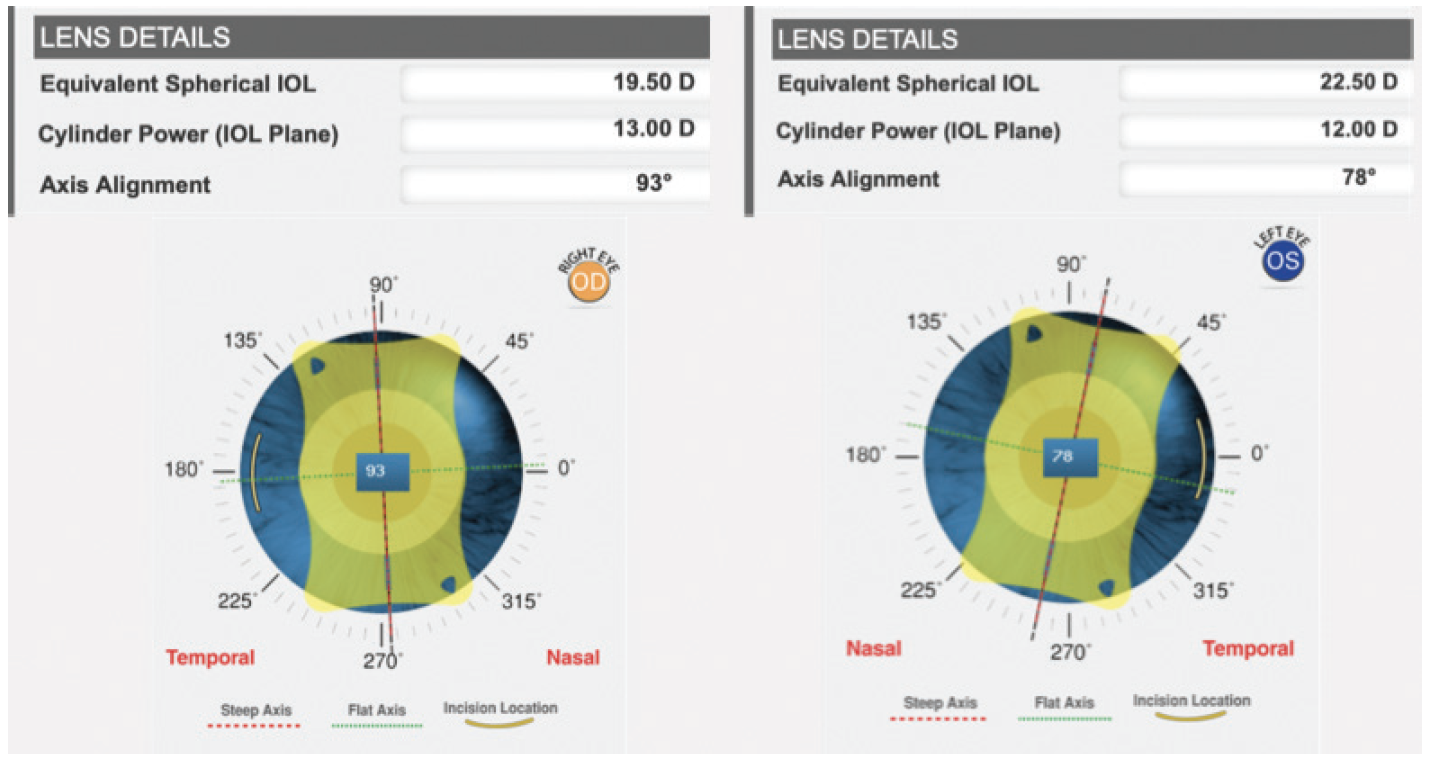

The IOL power calculations presented a challenge. I did some research online to find the lens constants and entered them into the Lenstar (Haag-Streit) to give me the spherical power of the IOL. I entered that power into VSY Biotechnology’s Acriva Easy Toric Calculator; a 19.50 D IOL with a cylinder power of 13.00 D and a 22.00 D IOL with a cylinder power of 12.00 D were recommended for the right and left eyes, respectively (Figure 2). The numbers gave me pause, but I realized that a high power was required at the IOL plane to create the desired effect at the corneal plane. I ordered two of each of the lenses in case one was scratched or damaged during insertion.

Figure 2. IOL power suggested by the Acriva Easy Toric Calculator.

SURGICAL COURSE AND OUTCOME

Surgery. On both eyes, surgery was straightforward. The Lensar Laser System with IntelliAxis (Lensar) was used to align the toric IOL based on iris registration with the OPD-Scan III (Nidek). Because I had no experience with the Acriva and it is a plate-haptic design, I placed a capsular tension ring in each eye to help prevent postoperative rotation of the IOL. Lens insertion was easy, and the process of axial alignment was familiar.

Outcome. The patient’s BCVA increased by 2 lines in each eye, from 20/25 to 20/15 OD and from 20/30 to 20/20 OS. The spherical equivalent achieved was reasonably on target, +0.375 D OD and -1.00 D OS. The astigmatism, however, was overcorrected, resulting in refractions of +1.50 -2.25 x 100º OD and plano -2.00 x 70º OS.

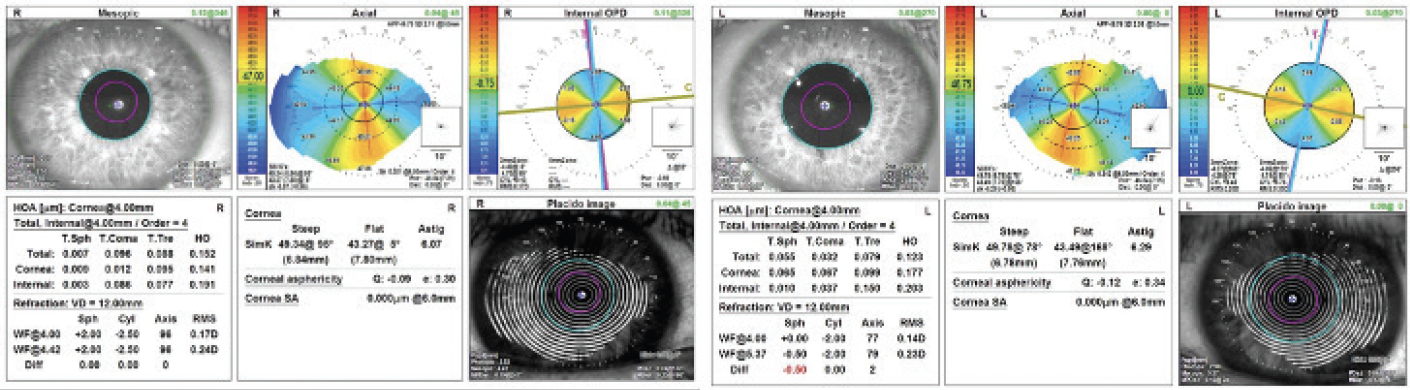

Initially, I thought the posterior cornea had caused an overestimation of total astigmatism. On further review, I realized that the phaco incisions placed horizontally at 180º in the right eye and 0º in the left eye caused approximately 2.00 D of flattening in the opposite meridian (Figure 3). Total anterior keratometry decreased by 2.33 D in the right eye (from 8.40 D @ 93º to 6.07 D @ 95º) and by 1.95 D in the left eye (from 8.24 D @ 79º to 6.29 D @ 78º). This experience highlights the unpredictability of surgically induced astigmatism in individual eyes. The tension on the steep corneal meridian must have been so significant that any incision would have flattened the cornea.

Figure 3. Dr. Smith’s postoperative topography measurements.

Postoperatively, Dr. Smith regained full functionality with glasses and contact lenses. He underwent an Nd:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy on each eye. We are currently considering a PRK enhancement.

LESSONS LEARNED

No. 1: Gratitude. I work in a field with smart colleagues and an innovative industry. When in doubt, it is prudent to ask for help.

No. 2: Persistence. New processes are challenging to navigate, but they can be broken into steps. The best way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time.

No. 3: Humility. Underpromise and overdeliver is a well-known mantra in cataract and refractive surgery for good reason. Despite the precision of available tools and advances in surgical algorithms, surprises occasionally occur. Every case can be educational.