CASE PRESENTATION

A 39-year-old woman underwent bilateral LASIK 20 years ago to treat approximately -8.50 D of myopia. The patient expressed a desire for a refractive enhancement.

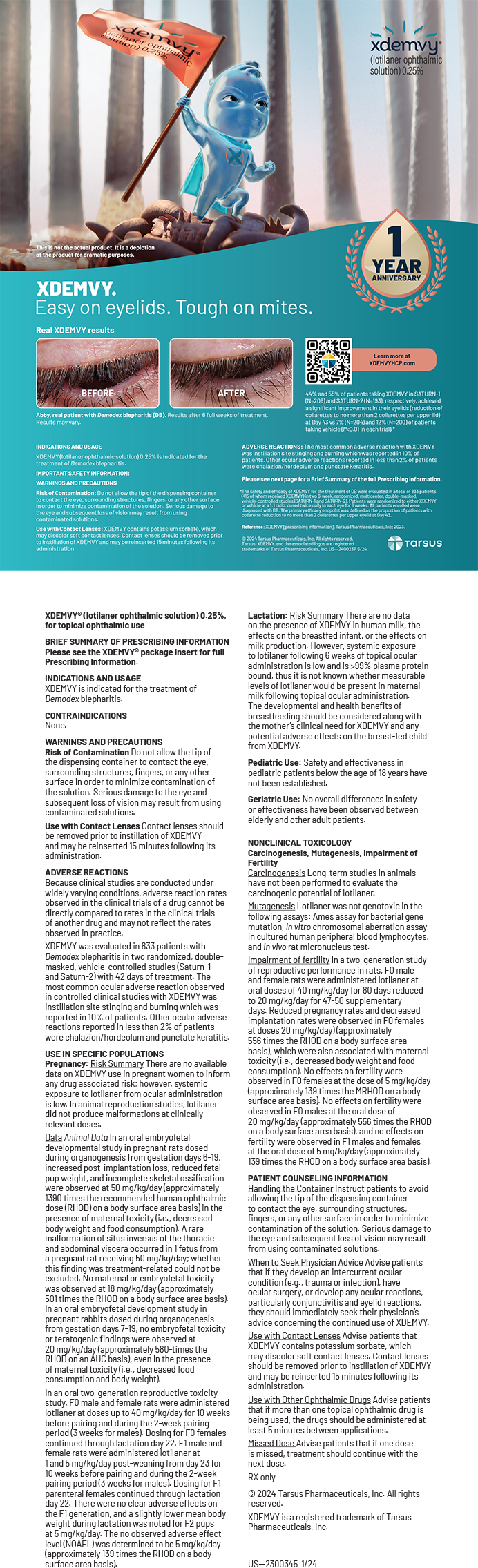

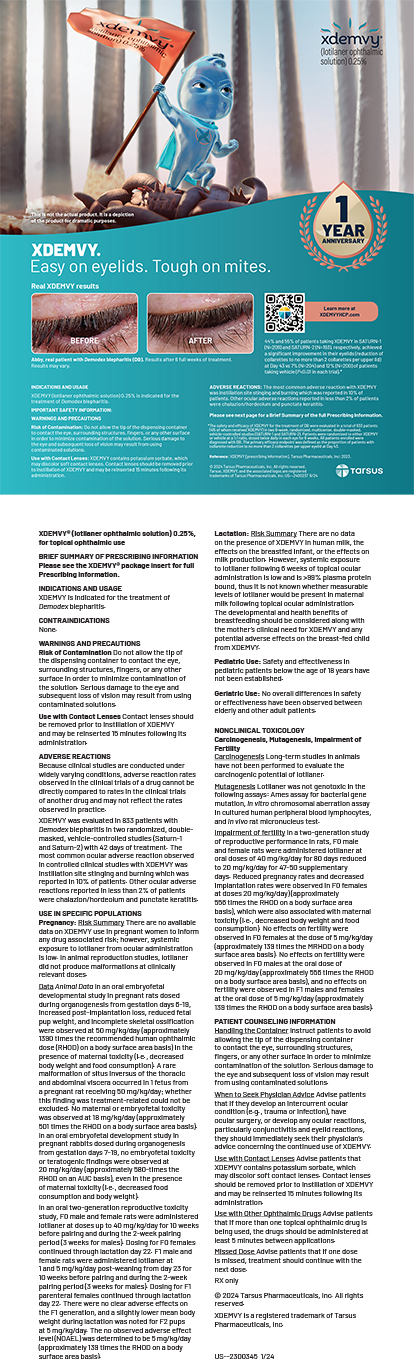

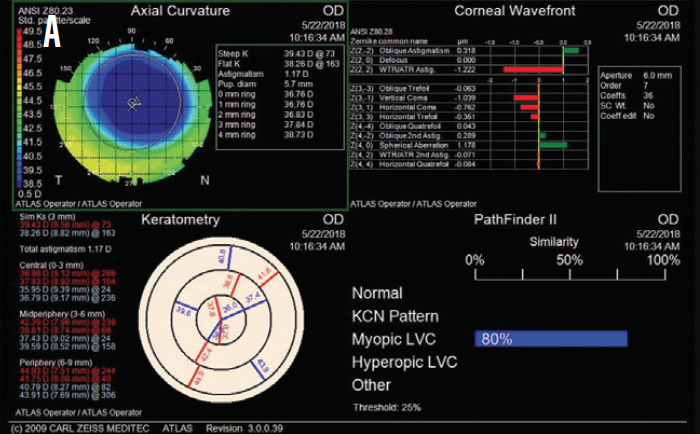

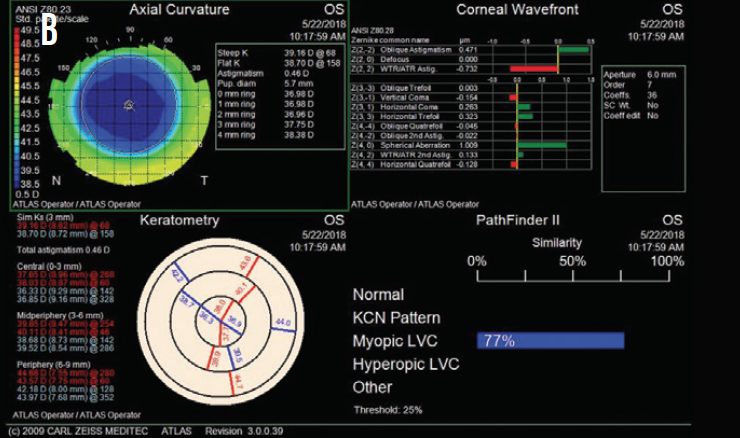

Upon examination, she had a manifest refractive error of -4.25 D and a pachymetry reading of 480 µm in each eye. Figure 1 shows topography measurements for each eye.

The patient complained of dry eyes. Intermittent foreign body sensation was controlled with artificial tears. A slit-lamp examination showed a slightly low tear film. Tear film breakup time was within normal limits, and there was no corneal or conjunctival staining.

Figure 1. Preoperative topography measurements of the patient’s right (A) and left (B) eyes.

How would you proceed?

—Case prepared by David A. Goldman, MD

ALLON BARSAM, MA, MBBS, FRCOphth

The patient has significant residual myopia and symptoms of ocular surface disease. Although topography shows no sign of late ectasia, the effective optical zone is only 4 to 5 mm. This accounts for the high positive spherical aberration. Similarly, the treatment zone may not be well centered on the entrance pupil, which could account for the remainder of the higher-order aberrations.

Several areas of the history and examination must be clarified. It would be reassuring to have optometric refractions over the past few years to confirm stability. It would also be important to know how the patient corrects her refractive error. For example, contact lens wear might account for the symptoms of irritation, in which case I would ask her to reduce wearing time significantly and I would treat any meibomian gland dysfunction to optimize the ocular surface prior to surgical intervention. In contrast, if the patient has fully corrected her refractive error with glasses, I would want to confirm that she does not have significant problems with her quality of vision with this form of correction. If she does, then it might be necessary to prioritize optimizing the corneal shape with a topography-guided treatment instead of using a more standard wavefront-optimized profile. If the point spread function simulated any problems with quality of vision, then I would favor a wavefront-guided treatment.

I would carry out a dilated examination that included a cycloplegic refraction to ensure that there is no accommodative element to the patient’s refractive error and to confirm that the lens is healthy and there are no early changes that could be causing index myopia. If there are such changes, then a laser vision correction enhancement would be unwise and a lens-based option preferable.

In my experience, most cases like this one result from an undercorrection of the initial refractive error, and the resultant blur can stimulate further myopic progression, which typically stabilizes after a few years. This patient would have been 19 years old when she underwent LASIK, so it is also possible that her refraction was not stable at the time of initial treatment.

Assuming the ocular surface has been optimized, the refractive error is genuine and stable, and the lens is healthy, I would proceed with a LASIK enhancement. I would not lift the flap after 20 years because the risk of epithelial ingrowth would be unacceptably high. I would perform corneal OCT (»Avanti Optovue, Haag-Streit) to measure both the epithelial and original flap thickness. Provided I could create a flap with the femtosecond laser that anteriorly cleared the original interface and posteriorly cleared the basal epithelium by at least 30 µm, my preference would be to make and carefully lift a new flap rather than to perform a surface enhancement with mitomycin C. I would target emmetropia in each eye with a 6.5-mm optical zone.

DOUGLAS A. KATSEV, MD

This post-LASIK patient has a common complaint, and the cause of her myopia warrants careful consideration. The most important first step, however, is to address her dry eye disease (DED).

Lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 0.5% (»Xiidra, Shire) would be my choice in this case because of its fast onset of action. Although I do not usually pair this agent with loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic ointment 0.5% (»Lotemax, Bausch + Lomb) for simple DED cases, I would do so here because time is often important in refractive surgery cases—especially true here. Additionally, I would consider the placement of punctal plugs to speed her recovery. Lifitegrast and punctal plugs treat DED in different ways, and I have found the combination to be excellent for patients like this one who are sometimes demanding. I would also recommend that the patient begin taking a nutraceutical. Lasine (MediNiche) is a reasonably priced DED supplement, and it was developed for patient use before and after LASIK and cataract surgery to improve tear quality.

After optimization of the ocular surface, the decision is between a LASIK enhancement and refractive cataract surgery. The patient is of early presbyopic age. Is the problem myopic regression after LASIK or a myopic shift caused by a nuclear sclerotic lens? Is she willing to undergo cataract surgery and incur the potential side effects of halos from a diffractive multifocal IOL or the occasional need for reading glasses if she receives an accommodating IOL? In cases that require such a high degree of myopic correction after refractive surgery, my preference is usually an accommodating lens (»Crystalens, Bausch + Lomb).

If the patient does not have a cataract, or if she prefers not to have lens replacement surgery, I would consider performing PRK or LASIK. Surface ablation would remove less tissue below the original flap and thus be more stable, and it would avoid potential complications related to relifting the flap such as epithelial ingrowth. The disadvantage of PRK relates to epithelial remodeling, which occurs when, over time, extra layers of epithelial cells alter the flattening produced by LASIK and cause regression. Removing epithelial cells for PRK and subsequent healing can make the target refraction hard to hit, necessitating a PRK touch-up.

My preference here would be PRK. Regardless of the method of laser vision correction selected, it would be important to explain to the patient preoperatively that additional touch-ups might be necessary.

WHAT I DID: DAVID A. GOLDMAN, MD

Although 4.00 D of myopia represents significant regression after LASIK, the patient’s age at the time of the original surgery suggests that some latent myopia might have been present and later developed. Furthermore, significant time had passed since her original treatment, which would warrant a large amount of regression.

Figure 2. Postoperative topography measurements of the patient’s right (A) and left (B) eyes.

Based on the patient’s current age, topography, and residual stromal bed thickness, I recommended PRK with a 30-second application of mitomycin C in each eye. One month after surgery, the patient’s UCVA was 20/20 OU, and she was ecstatic about the improvement (Figure 2).