Dry eye disease (DED) is a common condition that, left untreated, can have negative effects on postoperative outcomes of cataract surgery. It is well known that DED can lead to improper measurements for IOL selection, therefore affecting postoperative refractive outcomes. Additionally, DED can affect comfort of the eye and quality of vision, both of which negatively impact patients’ perception of the success of surgery.

This article explores five tips for successful IOL selection in patients with DED.

No. 1: Signs and symptoms don’t correlate. Signs and symptoms of DED are not well correlated. We have all seen patients who report severe DED symptoms but show few clinical signs, or the reverse, patients who have significant corneal staining but are asymptomatic.

This creates a paradox for surgeons: How do we talk about DED with our surgical patients, especially when they are asymptomatic? It is important to note that one of the main symptoms of DED is blurry, fluctuating vision. This should be distinguished from blurry vision due to cataract because, if ocular surface disease (OSD) persists after cataract surgery, the patient may still have impaired visual quality and function.

In my practice, I have adopted a systematic approach to cataract surgery assessment. During the initial workup, all patients are asked direct questions regarding symptoms of DED. I also have my technicians employ point-of-care diagnostic testing for DED, mainly for matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9; Inflammadry, Quidel) and tear osmolarity (TearLab Osmolarity System, TearLab). These tests provide objective metrics that both the patient and I can follow to monitor response to treatment. A multicenter study found that 85% of asymptomatic patients had an abnormal result for at least one of these objective tests, indicating that there is a high level of asymptomatic OSD in the cataract surgery population.1

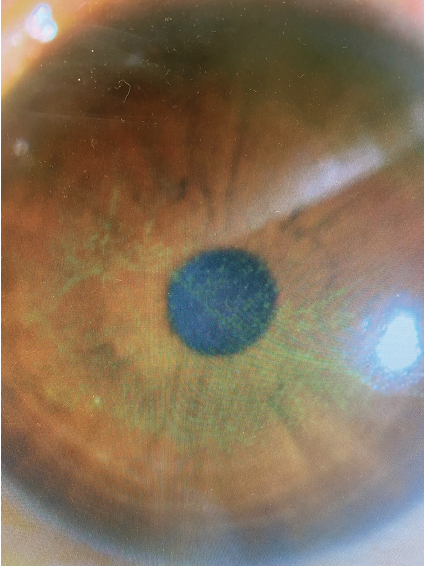

Next, I perform the clinical examination and vital dye tests to assess tear breakup time and corneal staining (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Corneal surface staining with fluorescein in a patient with DED.

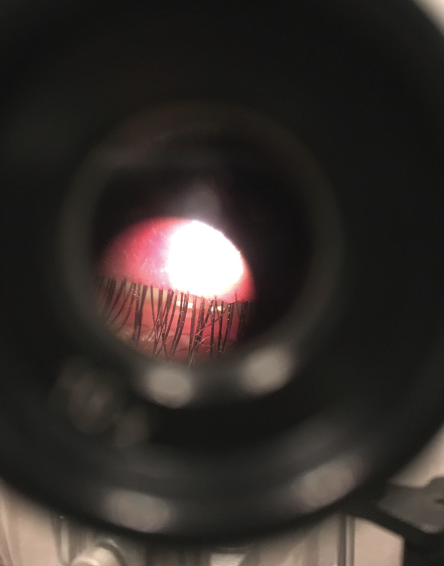

Aside from DED, there are other important ocular surface conditions to look for. These include meibomian gland dysfunction, a frequent contributor to DED (see Watch It Now); blepharitis, which can increase the risk for endophthalmitis; epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, which may contribute to irregular astigmatism; and lagophthalmos and other lid position disorders that may affect the ocular surface (Figure 2).

WATCH IT NOW

Dr. Brissette checks the ocular surface for meibomian gland dysfunction.

Figure 2. Lagophthalmos and other lid position disorders can affect the ocular surface.

No. 2: OSD will affect the refractive outcome of surgery. The measures just described may sound labor-intensive or time-consuming, but I can assure you that they are worth their weight in gold when it comes to surgical outcomes. Optimizing the ocular surface is imperative for excellent refractive outcomes and patient satisfaction. DED can impair IOL selection through its impact on keratometry values and measurements of magnitude and axis of astigmatism.

As cataract surgery technology has improved over the years, so have our outcomes—and so have the expectations of our patients for excellent vision after surgery. A healthy ocular surface is just as important to lens selection as the other biometric measures that we are constantly striving to optimize.

No. 3: Treat DED aggressively before scheduling surgery. Classical DED treatment is often described as a stepwise approach to therapy, starting with over-the-counter artificial tears and moving to prescription therapies, if needed, later in the treatment course. However, when we are treating preoperative patients with DED, it is important to rapidly reverse their ocular surface dysfunction and restore homeostasis to ensure stability for measurements.

To achieve this, it is beneficial to employ multiple therapies at once. I like to complement the basics such as artificial tears, warm compresses, and lid care with prescription DED therapies. For example, rapid reversal of corneal staining can be achieved with a short course of topical steroid (I prefer to dose b.i.d. for 2 weeks) concomitant with a long-term DED therapy such as cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% (Restasis, Allergan), cyclosporine ophthalmic solution 0.09% with nanomicellar technology (Cequa, Sun Ophthalmics), or lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 5% (Xiidra, Novartis).

For severe DED, in-office procedures can be beneficial, including punctal plugs and treatment of the meibomian glands with thermal pulsation or microblepharoexfoliation. The latter is especially beneficial in blepharitis.

No. 4: Proceed with surgery only when measurements are stable. The best recommendation for IOL selection can be made once the measurements are stable. After diagnosing and aggressively treating the ocular surface, I recommend repeating your clinical examination as well as biometry and/or topography to ensure the stability of measurements. Often, the magnitude and axis of cylinder and even the IOL power selection will have changed.

Once the surface has stabilized, I have no problem recommending a premium IOL, whether toric or diffractive multifocal. In patients with persistent or severe ocular surface concerns, I am more reticent to recommend a diffractive lens. One study found that the main reason for dissatisfaction after implantation of diffractive IOLs was DED. It is important, therefore, to discuss this potential in DED patients who request these lenses.3

No. 5: Continue DED treatment postoperatively. Not only is DED an important consideration preoperatively, but it is also a common complaint in the postoperative period. DED can worsen after surgery for many reasons, including toxicity from topical postoperative drops, diminished corneal sensitivity due to limbal relaxing incisions, and increased corneal staining in patients undergoing laser cataract surgery compared to standard phacoemulsification.4,5

These factors can tip asymptomatic patients into becoming symptomatic, which may affect their satisfaction after surgery. By starting a long-term regimen of DED therapy (with the basics and prescription drops) preoperatively, you are better positioned to avoid dissatisfaction in the postoperative period.

1. Gupta PK, Drinkwater OJ, VanDusen KW, Brissette AR, Starr CE. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery evaluation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(9):1090-1096.

2. Epitropoulos AT, Matossian C, Berdy GJ, Malhotra RP, Potvin R. Effect of tear osmolarity on repeatability of keratometry for cataract surgery planning. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:1672-1677.

3. Gibbons A, Ali TK, Waren DP, Donaldson KE. Causes and correction of dissatisfaction after implantation of presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1965-1970.

4. Yu Y, Hua H, Wu M, et al. Evaluation of dry eye after femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:2614-2623.

5. Cetinkaya S, Mestan E, Acir NO, Cetinkaya YF, Dadaci Z, Yener HI. The course of dry eye after phacoemulsification surgery. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:68.