The femtosecond laser fractures the cataractous lens in an instant, without the negative impacts of fluid infusion and ultrasound-generated heat associated with phacoemulsification devices. This capability gives new meaning to the term lens disassembly and suggests, among other things, that further opportunities may exist for lowering aggregate power requirements in emulsification and enhancing surgical efficiency. But, typical of how innovative technologies find their bearing and usefulness in medicine, we must be persistent in the application of appropriate clinical observation and scientific inquiry to connect the dots.

Consider that each element of the phacoemulsification procedure represents a unique risk: Heat is generated by the phaco needle, and fluid infusion and captured particulate lens material are jettisoned against the corneal endothelium, into the trabecular meshwork, and, yes, even into the vitreous cavity. And then there is the human element. So, when we speak of surgical efficiency and safety, we certainly aspire to lower effective phacoemulsification time (EPT), understanding that, for the most part, the more prolonged the procedure, the greater the risks.

Investigators comparing conventional phacoemulsification versus phacoemulsification plus femtosecond laser technology (referred to hereafter as laser cataract surgery) have entertained a mix of conclusions.1-4 However, our own investigations call into question some studies that may not speak to the deleterious late effects on the health of the eye after conventional phacoemulsification. It is here that laser cataract surgery, in conjunction with newly appreciated techniques and technological considerations, may provide opportunities to further improve outcomes.

UNDERSTANDING FLUID DYNAMICS

Our studies5 suggest that taking advantage of the potential for integrated laser cataract surgery requires a comprehensive understanding of the fundamentals of phacoemulsification-based fluid dynamics (FD).

FD, as it relates to phacoemulsification, encompasses an understanding of how fluid operates—not only fluid in the anterior chamber in the throes of emulsification, but how fluid is transported down the shaft of the phaco needle-sleeve complex and into the anterior chamber (see A Short Course on FD). For most of us mere mortals, FD is an arcane discipline, which explains why, over many years, the industry has focused on phaco needle design and handpiece functions. It is easier to contemplate power settings, needle designs, and oscillatory movements than the almost invisible, ephemeral machinations of fluid in the anterior chamber.

A Short Course on FD

Infusion fluid wends its way down and around the phaco needle within the silicone sleeve, then exits through the two infusion ports at the distal end of the sleeve. How that fluid train is influenced as it makes its way down and out of the infusion sleeve is important.

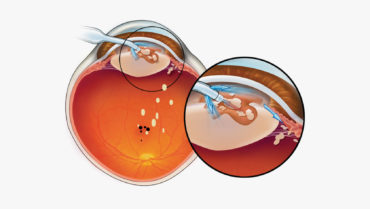

Aberrant infusion associated with fluid dynamics (FD) can be demonstrated in association with all manufacturers’ needle-sleeve designs currently on the market, and all act as spoilers to any attempts to tame the fluid chaos that rules the anterior chamber during phacoemulsification surgery. Using both slow-motion clinical and in-vitro high-speed video studies, we have demonstrated that, when infusion is balanced by a well-centered phaco needle within the infusion sleeve, the potentially obnoxious effects of aberrant infusion are mitigated and a triangular zone of relative fluid tranquility is promoted at the needle tip (Figure, A).

The genesis of aberrant infusion begins way up the needle-sleeve complex at the corneal wound, where the incision acts as a fulcrum, restricting movement of the infusion sleeve while leaving the phaco needle with free rein. As the surgeon moves the handpiece about from side to side, attempting to use aspiration to capture nuclear lens bits to the needle tip, the fulcrum inhibits the sleeve. As a result, the needle instantaneously blocks one port and encourages a flood of infusion into the anterior chamber from the contralateral port, resulting in a degrading effect to the triangle of tranquility and promoting fluid chaos (Figure, B and C).

Figure. Triangle of tranquility facilitated by a phaco needle centered within the infusion sleeve (A). Decentered phaco needle obstructing the left port, facilitated by the fulcrum effect, as fluid exits the right port, flooding the anterior chamber (B). Decentration of the phaco needle to the left within the silicone sleeve in association with obstruction of the left infusion port (C). Decentration of the phaco needle to the right, obstructing fluid exiting from right distal port and facilitating an excess of fluid from the left port. Note the early intraoperative floppy iris–like distortion of the iris to the left (D). Nuclear lens chips visible in the anterior vitreous immediately after conventional phaco and I/A (E).

The river of unrestrained fluid entering the anterior chamber from the open port visibly promotes iris movements similar to those in intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (Figure, D), inefficient lens followability, increased embarrassment to the corneal endothelium, and, more than occasionally, significant nuclear chips remaining in the anterior vitreous at the conclusion of the I/A portion of the seemingly pristine phaco procedure. This was the case in 24% of procedures in our studies (Figure, E).

As our study group began to focus on the needle-sleeve complex and its relationship to FD, we began to understand that FD plays an outsized influence on phacoemulsification—and not in a good way. We demonstrated the elements of aberrant FD and its negative impact on almost every anatomic structure in the anterior chamber, as well as the vitreous, and potentially the retina. Addressing these concerns, we surmise, may add further value to outcomes for those employing laser cataract surgery.

AN OVERLOOKED FACTOR

Our published studies suggest that attention to the factors that disturb normalized infusion and to the preservation of the triangle of relative tranquility has the potential to move laser cataract surgery procedures to another level of sophistication and, one would hope, improved outcomes.

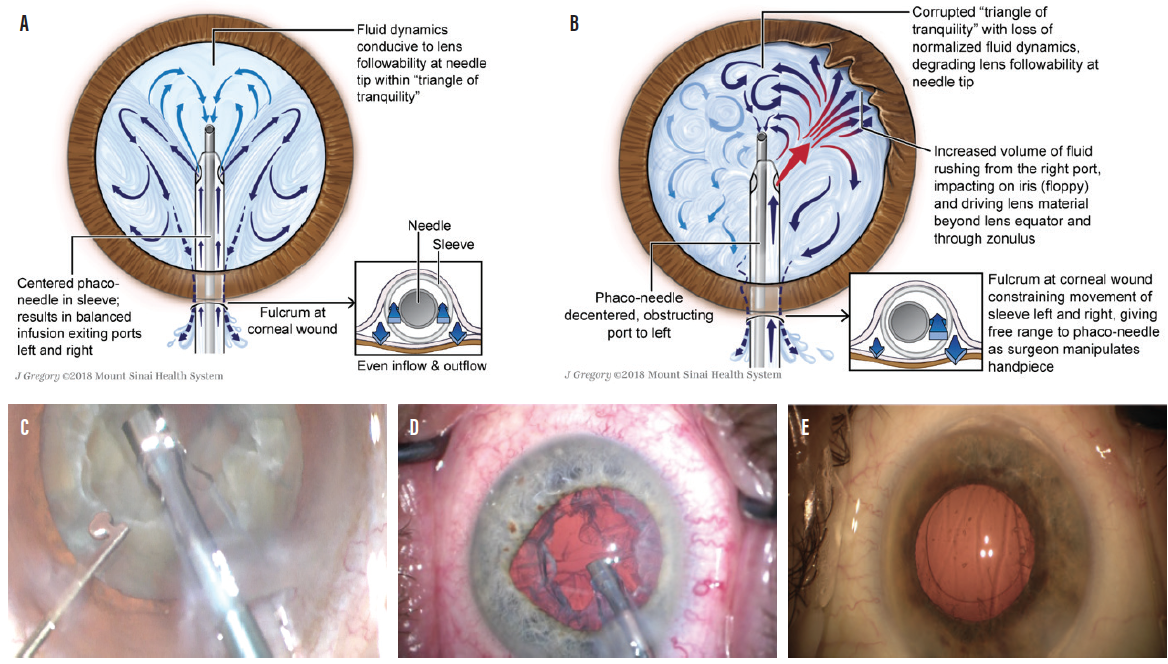

Previous studies comparing laser cataract surgery and conventional phacoemulsification may be ignoring an important denominator, which is late complications. Based on our studies, we posit that there are late complications (2–6 months postoperative) associated with phacoemulsification. In many cases, nuclear lens particulate is carried to the vitreous cavity by rivers of aberrant infusion during phacoemulsification. In virtually all cases, these lens chips, absent from view on day 1, then sink deeper into the vitreous cavity after surgery, with the potential of reaching sensitive areas of the retina including the macula. Here they may irritate the fovea and have the potential to trigger the development of postoperative cystoid macular edema and, in the longer term, possibly epiretinal membrane formation and macular pucker (Figure 1).6

Figure 1. Nuclear lens chips are driven by aberrant infusion into the vitreous cavity where, in dependent fashion, they may fall to the retinal surface, possibly provoking cystoid macular edema, late-developing epiretinal membranes, and macular pucker.

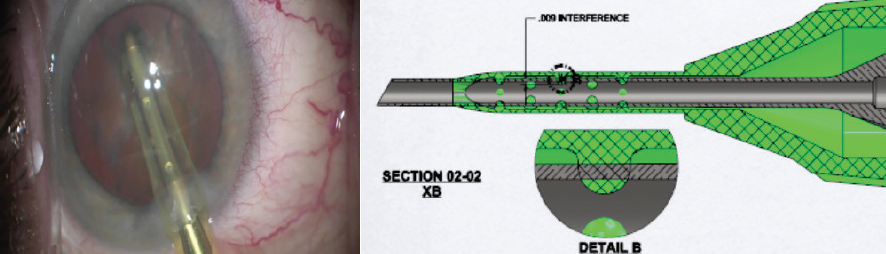

To encourage consistent needle centering, the authors have designed a phaco sleeve, the Sure-Path Infusion Sleeve (under evaluation in conjunction with Johnson & Johnson Vision). This sleeve technology supports centration of the phaco needle by using circumferentially placed centering stents that shepherd infusion fluid down the sleeve evenly, encouraging symmetrical exit from both unobstructed infusion ports (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Clinical demonstration of a centered phaco needle with stents maintaining patency of the distal infusion ports (left). Schematic drawing of needle-centering stents placed within the lumen of the infusion sleeve in circumferential fashion (right).

Centering the phaco needle within the phaco sleeve has a salutary effect on anterior segment FD. This enhances laser cataract surgery, encouraging more efficient and safer emulsification of the laser-treated lens within the triangle of relative tranquility. With the use of sleeve-centering technology, the laser-disassembled lens material remains more securely at the tip of the phaco needle, shortening EPT and decreasing the opportunities for aberrant infusion to insult anterior chamber structures (floppy iris) and for lens fragments to escape into the vitreous and retina.

CONCLUSION

Phacoemulsification is a long-standing and effective technique for cataract removal; however, in our studies, we found that ultrasonic disassembly of the nucleus may also encourage deleterious late effects particularly affecting the retina. We believe that laser cataract surgery with the incorporation of a technology that maintains a centered phaco needle within the sleeve—normalizing fluid infusion into the anterior chamber—provides the best opportunity to perform safe surgery with better postoperative outcomes.

1. Hatch KM, Schultz T, Talamo JH, Dick HB. Femtosecond laser-assisted compared with standard cataract surgery for removal of advanced cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(9):1833-1833.

2. Manning S, Barry P, Henry Y, et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery versus standard phacoemulsification cataract surgery: study from the European Registry of Quality Outcomes for Cataract and Refractive Surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(12):1779-1790.

3. Ewe SY, Abell RG, Oakley CL, et al. A comparative cohort study of visual outcomes in femtosecond laser-assisted versus phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):178-182.

4. Conrad-Hengerer I, Al Sheikh M, Hengerer FH, Schultz T, Dick HB. Comparison of visual recovery and refractive stability between femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery and standard phacoemulsification: six-month follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(7):1356-1364.

5. Koplin RS, Ritterband DC, Dodick JM, Donnenfeld ED, Schafer M. Untoward events associated with aberrant fluid infusion during cataract surgery: Laboratory study and corroborative clinical observations. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(8):1035-1040.

6. Oh JH, Chuck RS, Do JR, Park CY. Vitreous hyper-reflective dots in optical coherence tomography and cystoid macular edema after uneventful phacoemulsification surgery. PLoS One. 2014;9(4) e95066.