I recently performed cataract surgery on a deaf 93-year-old woman with exceptionally dense bilateral cataracts that were complicating her macular degeneration, leaving her with only hand motion vision. The patient lives alone in a remote, rural cabin, so the loss of vision was of great concern.

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia. As I typically do in eyes that have exceptionally dense cataracts, I stained the capsule with trypan blue ophthalmic solution to augment visualization during surgery.

The patient had small pupils. Although I might have been able to remove a softer nucleus without assistive devices, I was concerned about maintaining dilation throughout the case, given the potential duration of surgery and expected amount of irrigating fluid and ultrasound power. I therefore used a dispersive ophthalmic viscosurgical device for viscomydriasis and then placed a Malyugin Ring (MicroSurgical Technology), which I find much easier to insert prior to the capsulotomy. Then, I created the capsulorhexis using a bent-needle cystotome and began to hydrodissect the lens to achieve good mobility of the nucleus within the confines of the capsule.

INSTRUMENTS

Even in eyes with extremely dense cataracts, I used a phaco needle with a refined edge such as the Packard Phaco Tip With Dewey Radius Bevel (MicroSurgical Technology). Although many surgeons would assume that a sharp edge is needed to break through such a dense nucleus, I favor the safety of the round edge. Anticipating that I would need a mechanical advantage for chopping, I retracted the irrigating sleeve to expose more of the needle than in a typical case. I carefully aligned the irrigating ports to be parallel with the iris to avoid directly irrigating the endothelium.

I also used a specialized chopper (Dewey Horizontal Femto Chopper; Rhein Instruments) that has a tip the same size as the shaft so that it fits through a 23-gauge incision. I find that this instrument provides a more stable, nonleaking sideport incision, even though I still have to enlarge the external aspect a little to ease the access of the viscoelastic cannula.

THE CHOP

With the chopper, I pushed the nucleus away slightly and then, using the Whitestar Signature Pro Phacoemulsification System (Abbott) in peristaltic mode, I applied high vacuum bevel down with minimal power. This application of high vacuum essentially pulled the nucleus onto the needle instead of my pressing down to achieve impalement. In dense cataracts such as this one, the irrigation sleeve stops the progress of the needle, so I need not worry about its passing all the way through the nucleus to the capsule, even when the sleeve is somewhat recessed.

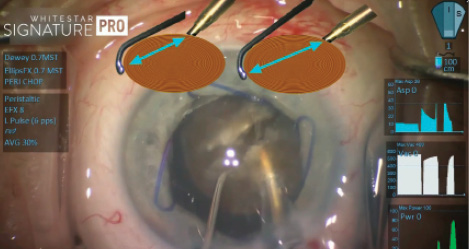

Figure 1. Ideal positioning of the phaco tip and the chopper, shown in the graphic on the right, to allow for maximum mechanical leverage during the horizontal chop.

By pushing the nucleus away from the incision, I was able to engage the phaco needle at a more proximal position of the nucleus relative to the distal placement of the chopper. With the nucleus impaled, which I sustained by remaining in foot position 2 (linear vacuum), I placed the chopper under the capsule and wrapped it around the equator of the nucleus. Through this separation of the two instruments, I optimized my mechanical chopping advantage and pulled them together (Figure 1). A leathery posterior plate proved challenging to split, despite optimal positioning.

Upon reviewing video of this case, it was evident to me that the high vacuum (approximately 550 mm Hg) did the majority of the work by pulling the nuclear material into the phaco needle. That kept me from having to push down onto the posterior capsule and thus prevented stress on the zonules.

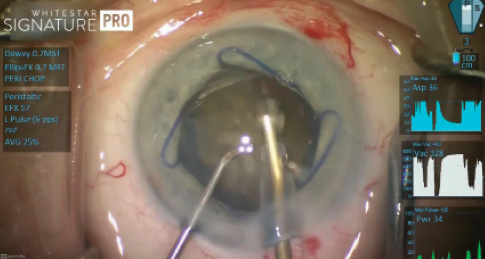

Figure 2. Dr. Dewey performed the procedure with high vacuum (555 mm Hg here) and small pulses of low power (0% here, low-powered pulses shown in green).

ULTRASOUND

Throughout the case, the delivery of ultrasound energy was very low. The duration of the case, however, meant that a lot of power was used. Unlike in a very similar case of a dense nucleus I performed 10 years ago with the same phaco technology, I did not need to use 100% power at any point during surgery (Figure 2), and I ended up using 65% less power than a decade ago. The ultrasound efficiency and “followability” were in large part a result of the variable-pulse, power-modulating technology available in the current generation of phaco machines.

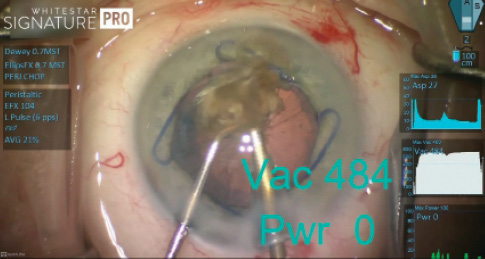

Figure 3. Inadvertent contact with the posterior capsule under high vacuum and zero power.

CAPSULAR CONTACT

As I got to the final quadrant removal, I was so focused on keeping the ultrasound power directed posteriorly (so as not to damage the endothelium) that I inadvertently grabbed the capsule (Figure 3). At that moment, the vacuum was still very high (484 mm Hg), but I would likely have captured this capsule even at much lower vacuum. Fortunately, the power was at zero. As demonstrated by Randall Olsen, MD, and his group, it is possible to interact with the capsule even with a sharp-tipped needle as long as there is no power.1 Even so, I maintain the use of a rounded needle, because a sharp edge can cut or shred the posterior capsule if I happen to be applying power at the same time.

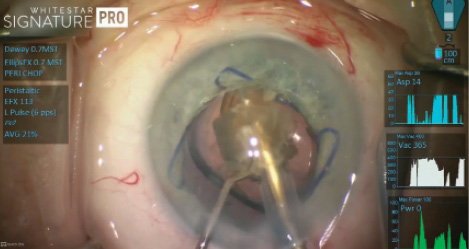

Figure 4. Removal of the last nuclear fragment, with the IOL and a Malyugin Ring in position.

I could have enlarged the incision at this point to express the remaining quadrant, but I really wanted to preserve the small incision and continue with my surgical plan. I went ahead and implanted a posterior chamber lens. Then, I gingerly continued phacoemulsification of the remaining fragment at the iris plane, while taking care not to etch the anterior surface of the lens (Figure 4). To minimize damage to the endothelium, I continued applying very small bursts of power and confining the phaco work to the surface of the fragment until, gradually, all of the material disappeared into the lumen of the needle.

WATCH IT NOW

See how Steven Dewey, MD, handled this case.

CONCLUSION

Postoperatively, there was some corneal edema, of course, but less than I might have expected after a 15-minute case. Today, the patient is back at home enjoying better eyesight. It was a delight to be able to help her maintain her independence.

1. Meyer JJ, Kuo AF, Olson RJ. The risk of capsular breakage from phacoemulsification needle contact with the lens capsule: a laboratory study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(6):882-886.