Recent advances in IOL design and manufacturing have improved the lenses’ safety, efficacy, and longevity while reducing—but not eliminating—complications. Occasionally, an IOL may behave like a magnet inside the eye, attracting deposits that can impair vision.

CASE NO. 1: GLISTENINGS

A 62-year-old man presented with a BCVA of 20/100 OS. He had undergone cataract surgery at another facility 4 years earlier and began to experience dimness of vision in the left eye 1 year ago.

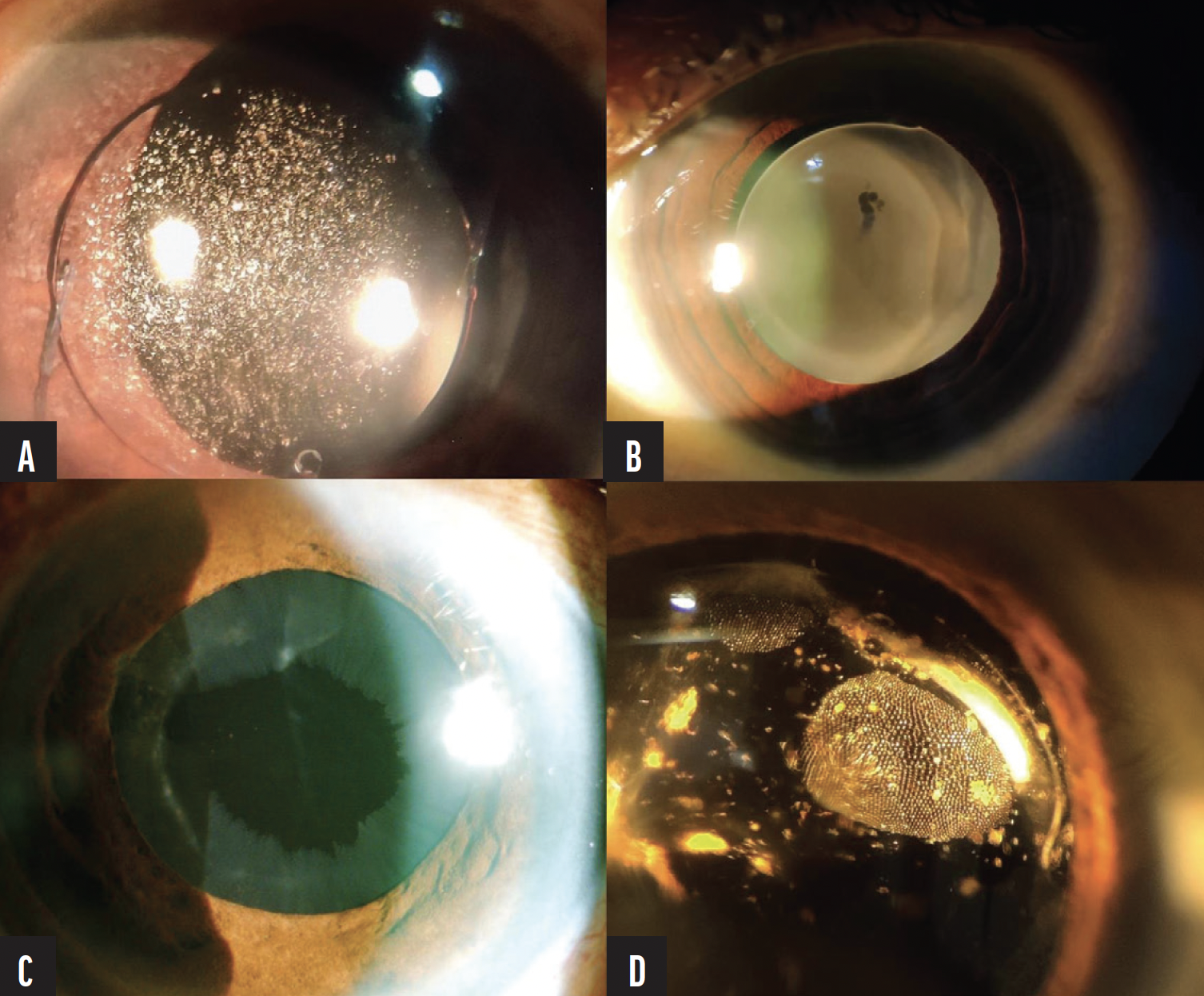

A slit-lamp examination revealed an anteriorly dislocated multipiece IOL with multiple glistenings (Figure A). These fluid-filled microvacuoles (10–20 µm) can develop within an IOL optic as early as 1 week postoperatively, and they tend to increase in size and density over time.1 Glistening formation is attributed to temperature fluctuations during the manufacturing or storage of lenses and may be linked to the injection molding process used in IOL production. Although most patients’ distance visual acuity is unaffected,2,3 glistenings can reduce the quality of vision by increasing light scatter and are thought to reduce contrast sensitivity. Most affected patients need only reassurance, but those who experience significant visual disturbances may require an IOL exchange.

Given the extent of glistenings and inadequate capsular support in this case, IOL explantation, pars plana vitrectomy, and scleral fixation of a hydrophobic foldable acrylic IOL were performed, leading to good postoperative visual recovery.

Figure. Four years after cataract surgery, anterior dislocation of a multipiece IOL with multiple glistenings is observed in a 62-year-old man (A). A one-piece hydrophilic acrylic IOL with an opacified optic is well positioned in the bag in the eye of a 78-year-old man 8 years after cataract surgery (B). A peripheral circumferential pattern of pseudoexfoliative deposits is visible on the anterior surface of an IOL in the eye of a 70-year-old woman (C). A honeycomb pattern of residual silicone oil droplets is seen on an IOL in the eye of a 60-year-old woman who underwent retinal detachment repair with silicone oil tamponade (D).

CASE NO. 2: OPACIFICATION

A 78-year-old man presented with a BCVA of 20/200 OD. He had undergone cataract surgery at another facility 8 years earlier and developed dim vision in the right eye 2 years ago.

Upon examination, the IOL was well positioned in the capsular bag, but the lens optic was opaque (Figure B). According to the patient’s previous records, the implant was a one-piece acrylic hydrophilic IOL.

IOL opacification is a rare complication reported predominantly in hydrophilic IOLs.4 In primary opacification, a defective polymer, improper fabrication, or poor packaging leads to calcium salt deposition. In secondary lens opacification, calcification results from changes in the surrounding environment, such as alterations in the aqueous humor or disruption of the blood-aqueous barrier.5,6 A calcified IOL typically has a cloudy appearance, often mistaken for posterior capsular opacification, and causes varying degrees of visual impairment. If the patient’s vision is severely compromised, the retina and cornea are healthy, and capsular support is adequate, an IOL exchange is the only effective treatment option.

Capsular support of the lens in this case was adequate. The opacified IOL was successfully exchanged for a multipiece hydrophobic foldable acrylic IOL, fully restoring the patient’s vision.

CASE NO. 3: PSEUDOEXFOLIATIVE DEPOSITS

A 70-year-old woman presented for a routine annual visit. On examination, her BCVA was 20/20, and the IOP was 24 mm Hg in both eyes. In the left eye, the IOL was well positioned in the bag, but a flaky white substance was observed on the lens’ anterior surface in a peripheral circumferential pattern, suggestive of pseudoexfoliative deposits (Figure C). Glaucomatous changes to the optic disc and significant thinning in the inferior quadrant of the retinal nerve fiber layer were noted. The patient was diagnosed with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma and underwent structural and functional testing. Medical therapy was initiated.

Pseudoexfoliative deposits are commonly found on the anterior lens capsule but rarely on an IOL. After cataract surgery and IOL implantation, the potential space between the iris and the IOL increases, reducing friction and allowing exfoliative material to accumulate gradually on the IOL’s surface.7 The peripheral circumferential pattern observed in this case differed from that seen on a crystalline lens, likely owing to aqueous flow patterns. The central and marginal deposits might have been washed away by the aqueous humor, while the intermediate zone—closer to the iris and less exposed to fluid dynamics—allowed deposits to accumulate.8

Identifying pseudoexfoliative deposits on an IOL is crucial because they may be the only visible sign of secondary glaucoma, as in this case.

CASE NO. 4: SILICONE OIL DEPOSITS

A 60-year-old woman underwent retinal detachment repair with silicone oil tamponade. Three months later, the silicone oil was removed, and cataract surgery with implantation of an AcrySof IQ lens (model SN60WF, Alcon) was performed. One month later, a honeycomb pattern of residual silicone oil droplets was observed on the IOL (Figure D). The deposits were peripheral to the visual axis and did not cause visual impairment. Because the visual axis was not obscured, we opted for observation without further intervention.

The hydrophobicity of silicone oil influences its interaction with IOLs. The more hydrophobic the lens biomaterial, the greater the adherence of silicone oil. Conversely, the more hydrophilic the lens material, the less adherent silicone oil.9 Silicone IOLs have the highest affinity for silicone oil, so these lenses should be avoided in eyes with silicone oil in situ. Deposits within the optical zone may greatly disturb the patient’s vision. Although an IOL exchange is commonly considered in such cases, less invasive approaches, such as hydraulic squeegee techniques and manual dislodgement using a silicone sweeper, may be attempted.10

CONCLUSION

Although the incidence of IOL-related complications has decreased significantly owing to technological advances, complications can still occur. Early recognition and timely management are essential for optimal visual outcomes.

1. Behndig A, Mönestam E. Quantification of glistenings in intraocular lenses using Scheimpflug photography. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35(1):14-17.

2. Colin J, Orignac I. Glistenings on intraocular lenses in healthy eyes: effects and associations. J Refract Surg. 2011;27(12):869-875.

3. Mönestam E, Behndig A. Impact on visual function from light scattering and glistenings in intraocular lenses, a long-term study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(8):724-728.

4. Neuhann IM, Kleinmann G, Apple DJ. A new classification of calcification of intraocular lenses. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):73-79.

5. Darcy K, Apel A, Donaldson M, et al. Calcification of hydrophilic acrylic intraocular lenses following secondary surgical procedures in the anterior and posterior segments. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(12):1700-1703.

6. Khurana RN, Werner L. Calcification of a hydrophilic acrylic intraocular lens after pars plana vitrectomy. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018;12(3):204-206.

7. Hepsen I, Sbeity Z, Liebmann J, Ritch R. Phakic pattern of exfoliation material on a posterior chamber intraocular lens. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87(1):106-107.

8. Kumaran N, Girgis R. Pseudoexfoliative deposits on an intraocular lens implant. Eye. 2011;25(10):1378-1379.

9. Apple DJ, Isaacs RT, Kent DG, et al. Silicone oil adhesion to intraocular lenses: an experimental study comparing various biomaterials. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23(4):536-544.

10. Lisa B, Nick M, Deepinder D, Christopher D, et al. Oil droplets on IOL. Cataract & Refractive Surgery Today. March 2007;7(3):43-44. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://crstoday.com/articles/2007-mar/crst0307_06-php