Like many good ideas, mine started with an accident (or more like a train wreck). A family friend had driven more than 100 miles so I could perform his cataract surgery. He chose a multifocal IOL because spectacle independence was important to him. Despite moderate intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, surgery on his first eye went great. Surgery on the second eye, however, was one of the most difficult cases of my career. The upside is the experience led me to an innovative idea.

POINT OF INSPIRATION

The problem. During surgery on my friend’s second eye, the leading eyelet of a capsular tension ring (CTR) became entangled in capsular folds. During the blind implantation of the CTR beneath the iris, the device was deployed against the entanglement, causing a zonular dialysis of more than 180º. The situation got worse. During placement of a modified CTR, the anterior capsule tore at the eyelet, and all capsular support was lost.

The solution. The difficult case led me to start tinkering with a better way to implant CTRs. After many months of trial and error, I came up with a modified design to simplify CTR insertion. I can’t share proprietary details yet—my idea is still in development—but I can share my experience as a guide to what to expect when bringing the idea in your head into your hands and the OR (Figures 1 and 2).

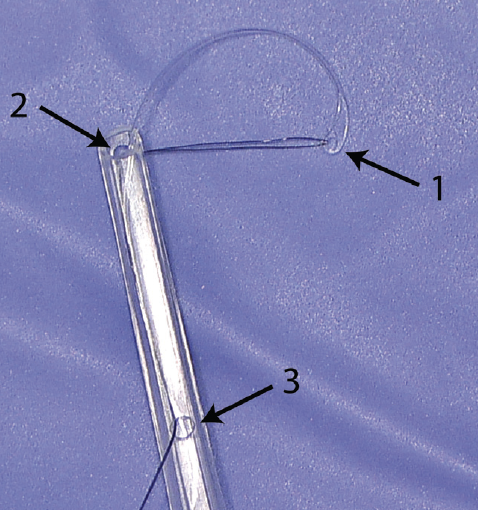

Figure 1. A prototype of the Suture Guided CTR. The device includes a visible tracing suture in the leading eyelet (arrow 1), distal port that allows the surgeon to bring the leading eyelet to the tip of the injector at any time during insertion (arrow 2), and proximal port to allow the surgeon to grasp the steering suture with tying forceps outside of the eye without the need for a second instrument in the eye (arrow 3).

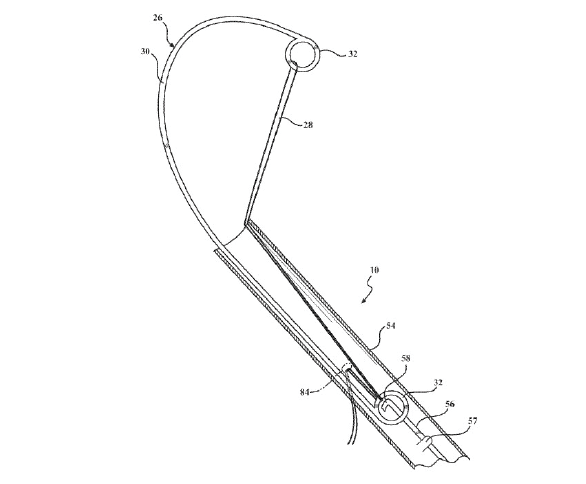

Figure 2. A patent illustration of the Suture Guided CTR.

DOCUMENT BEFORE YOU SHARE

If you have a good idea, chances are you’ll want to share it with everyone you know (friends, colleagues, industry) and publish it in the scientific literature.

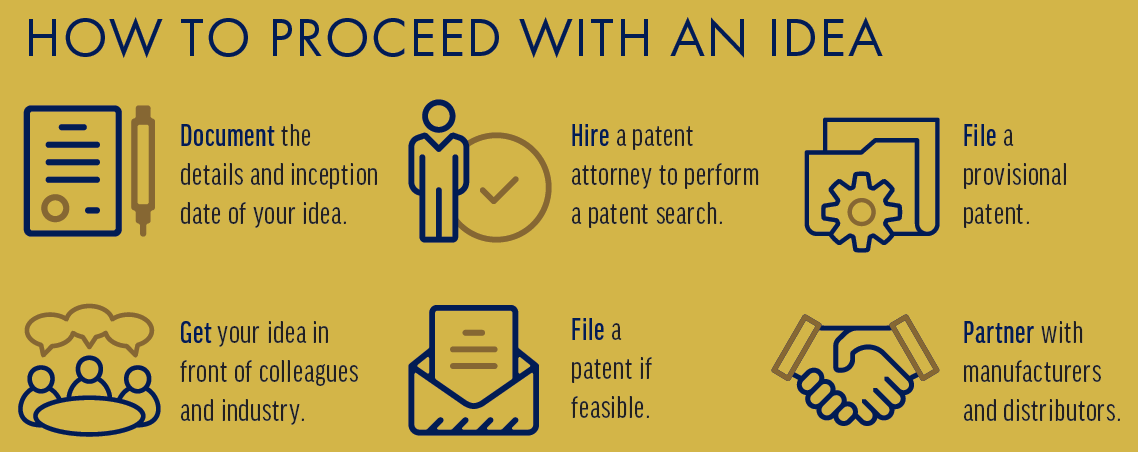

Before you make any public disclosure, document and date your idea. It doesn’t have to be a formal filing. Simply create a journal entry on your computer. Second, have a qualified patent attorney perform a patent search to see if any form of your idea already exists. In patent parlance, this is called prior art. If there is no prior art, consider filing a provisional patent. This service may cost several thousand dollars, but it helps protect your idea as you speak to potential partners and ultimately patent your own idea. (For more on patent law, see “Patent Law in Ophthalmology.”)

A provisional patent lasts only 12 months. Once you have one, it’s time to get to work. Share the idea with trusted colleagues and consider publishing it and presenting it at conferences. This can attract attention to your idea and open some doors with industry.

Every company in ophthalmology has a development division, and one of those employees will likely meet with you if your product fits their company’s portfolio. Your patent attorney can provide a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) so that any proprietary information you share is protected. Most NDAs are standard, and companies will likely have their own NDAs.

Larger companies may show interest in your idea. They may not, however, want to become involved until they see that it has some market value or because they cannot manufacture the product. In the latter situation, you may need to partner with a smaller company for manufacturing. For example, I was surprised to learn that only a few companies in the world manufacture CTRs, so for me the pool of potential partners was small.

NEXT STEPS

The patent process. If industry is interested in your idea, the next move is to decide whether to patent your idea. By this point, the provisional patent is likely nearing expiration. The choices are to extend it for an additional cost or file a US patent. The latter is the better option if your idea is gaining momentum. Also consider filing a patent in foreign countries. A patent attorney can help identify countries where you should file. In general, if a country can manufacture and distribute your idea, it is wise to protect your intellectual property there.

Brace yourself. Filing for US and foreign patents often costs more than $100,000 initially and thousands of dollars more in annual costs.

Consider the patent process carefully. Some ideas and devices don’t need to be patented. With good marketing and distribution, such products may be successful without the cost and hassles of the patent process.

Choose a partner. Deciding which company to partner with is an important decision. If you have the luxury of choosing between two or more companies, select the one with which you have the strongest and most trusting relationship.

Manufacturing your idea is only half the battle. Some companies can develop your idea but do not have a distribution channel. For example, when my idea stalled with a European company owing to a series of events, including Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, I sought US companies. I found companies that could manufacture my product, but they had no distribution network. This forced me to rely on independent salespeople to get the product into hospitals, offices, and ambulatory surgery centers.

Once arrangements are in place for manufacturing and distribution, there are several routes for compensation. Your patent can be reassigned, sold, or licensed. With the last of these scenarios, a royalty is awarded to the original patent holder as a percentage of sales. Consult a patent attorney to determine the best route for you.

Find mentors. Bringing an idea to market takes time (usually years), patience, and perseverance. There will be many highs and lows. Find mentors to guide you through the process, and trust your instincts.

CONCLUSION

What happened with the patient who inspired my idea? On postoperative day 2—which happened to be New Year’s Eve—he called me complaining of new floaters. By the time he got to my office, it was late at night. I noticed a posterior vitreous detachment with multiple peripheral hemorrhages. I escorted him to our retina service, and luckily no tear or detachment was found.

The next morning—New Year’s Day—the patient complained that he could barely see light. I brought him back to the office and found his vision to be light perception due to a hypopyon. Amazingly, he recovered 20/25 vision. The following week, he sent me a thank you card and a nice bottle of wine.

Sometimes, we get lucky with our patients. Other times, we don’t. The same can be said for big ideas, but you’ll never know if you don’t try.