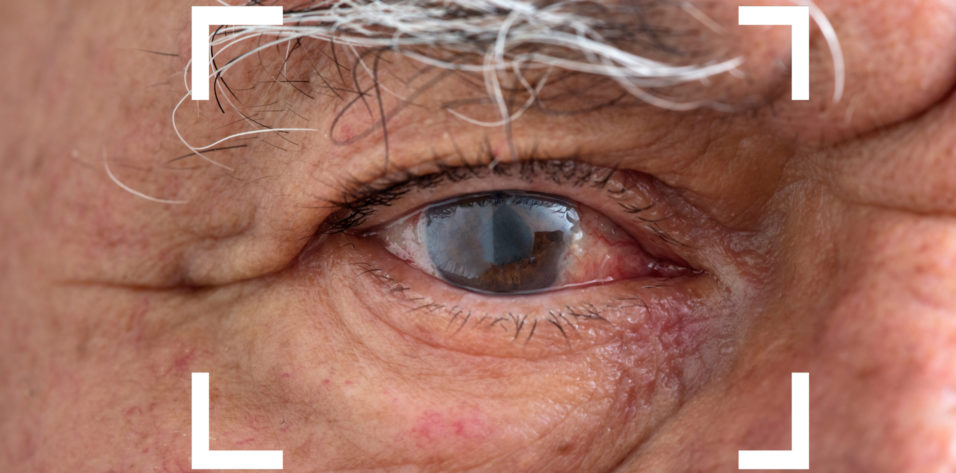

Chronic or recurrent inflammation, including cystoid macular edema (CME), occurs in about 0.1% to 2% of patients following routine cataract surgery.1 Prolonged postsurgical inflammation, though relatively rare, can be frustrating for both patients and practitioners. Risk factors include a history of uveitis or diabetes and long and/or complicated surgery.2 In some cases, an indolent infectious organism introduced at the time of surgery leads to chronic or recurrent postoperative inflammation.3

AT A GLANCE

- Chronic inflammation following cataract surgery is rare and often idiopathic. A collaborative care arrangement can be beneficial to the patient. An early referral by the anterior segment surgeon to the retina specialist is recommended.

- For patients with risk factors for severe and/or prolonged postoperative inflammation, a long, slow taper of a topical steroid is warranted.

- For patients who experience recurrent or recalcitrant inflammation after cataract surgery on the first eye, a longer initial taper of a steroid is recommended after surgery on the second eye.

- Patients with chronic postsurgical inflammation should be seen at frequent intervals to monitor their response to the tapering process and determine whether another intervention, such as an intravitreal injection, is warranted.

Practicing at an academic referral center, I regularly comanage patients who develop chronic inflammation after cataract surgery. Most of these individuals present to my practice 6 to 12 weeks postoperatively—sometimes because the referring surgeon detected CME with OCT and sometimes because the patient reported blurred vision, photophobia, and/or pain. This article shares my tips on successful management and comanagement.

DIAGNOSIS

I choose diagnostic tests depending on the patient’s status upon referral. If the individual has relatively mild inflammation and a straightforward history, then topical steroids are restarted and tapered over a 3-month period. If the inflammation is severe, then a workup is performed to rule out other infectious and inflammatory etiologies, particularly before an intraocular steroid injection is considered. The examination includes a uveitis workup and, on a case-by-case basis, an anterior chamber tap for polymerase chain reaction or culture. A workup is also in order if something such as plaque is observed on the lens that may be suspicious for infection. Much of the time, the inflammation presents primarily in the anterior chamber; I have a lower threshold for a complete uveitis workup if vitreous haze is evident.

Some patients who experience chronic or recurrent postoperative inflammation after cataract surgery on their first eye develop it after cataract surgery on their second eye. Generally, if any of the aforementioned features are present, then I perform an additional evaluation. Otherwise, I bear in mind that these patients may have a predisposition to inflammation due to unidentifiable factors.

TREATMENT ALGORITHM

If a patient is diagnosed with chronic or recurrent postoperative inflammation 6 to 8 weeks after cataract surgery, then the postoperative steroid is typically restarted (usually at a higher dose). If the inflammation is severe, then dosing may be as frequent as every 2 hours for a few days before being tapered. If the inflammation is mild to moderate, then the steroid is administered four times per day. The presence of CME may warrant an extended taper.

Patients are usually asked to return at about 6 weeks. If the eye is quiet and the CME has resolved, then the steroid is tapered over the following 2 to 3 months; the patient returns after the taper ends. If this is the first time a patient has performed a steroid taper, then I wait 4 weeks to bring them back. If they had a previous, more rapid taper, however, I may ask them to return sooner.

THREE SCENARIOS

After another 4 to 6 weeks, the patient is reassessed for recurrent inflammation. At that time, one of three scenarios is encountered.

Scenario No. 1: No inflammation. Usually, the eye is quiet, in which case there is nothing more to do.

Scenario No. 2: Recurrent inflammation. A subset of patients return with recurrent inflammation at or before this follow-up visit. In the presence of recurrent inflammation, either the steroid taper can be extended, which may not be effective, or the dosing frequency of the topical steroid can be increased while authorization from their insurance company is requested to administer an injectable medication such as the dexamethasone intravitreal implant 0.7 mg (Ozurdex, Allergan).

I instruct patients to stop all topical medications on the day they receive a dexamethasone intravitreal implant and ask them to return in 6 to 8 weeks for an IOP check and anterior segment evaluation. I see patients with elevated IOP or glaucoma sooner to monitor their pressure. In some situations, it is appropriate to start IOP-lowering therapy when the dexamethasone intravitreal implant is placed. Often, patients need just one of these implants and respond well.

Scenario No. 3: Rebound inflammation. An even smaller subset of patients develops rebound inflammation and may experience a second or third recurrence. In this situation, I may propose a longer-acting intraocular implant such as the fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant 0.18 mg (Yutiq, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals).

Patients who have been on long-term topical and/or intraocular therapy often prefer the option of a single injection that lasts 3 years. I do not have any patients who are a full 3 years out from treatment yet, but none of them has experienced a recurrence so far.

Recently, I saw a patient with persistent postoperative inflammation and placed a dexamethasone intravitreal implant after three unsuccessful attempts at tapering topical corticosteroids (a standard postoperative taper followed by an extended taper over 2 months and then an even longer taper because the patient initially wanted to avoid intravitreal injection). He responded well to the implant but experienced a recurrence of inflammation at the 4-month mark. A second dexamethasone intravitreal implant was placed, followed by the placement of a fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant 8 weeks thereafter. Nine months later, he is doing well and has not experienced recurrent inflammation.

COMANAGEMENT

Effective comanagement between anterior segment surgeons and retina specialists can be professionally rewarding and beneficial to patients who experience chronic or recurrent inflammation after cataract surgery. The practice setting can make comanagement challenging. At my multispecialty academic center, however, I find it easy to provide a consultation to a colleague in person on relatively short notice. Whether a referral comes from within my institution or an outside practice, I make sharing my findings and treatment plan with the referring physician a priority. I try to document them formally in writing, but I also find it helpful to make a quick phone call or send a text message. Dealing with postoperative inflammation is stressful for patients and their physicians, so I attempt to update the cataract surgeon on the patient’s status regularly.

If a patient presents with persistent postoperative inflammation in one eye and cataract surgery is planned for the second eye, then the referring surgeon and I may collaborate on a course of treatment for the next surgery. Even if the first eye had mild inflammation that ultimately resolved, I am still likely to recommend an extended (3 months vs 1 month) taper at the outset. If the patient has uveitis and particularly severe inflammation in the first eye, then the anterior segment surgeon and I may discuss a preoperative injection of a dexamethasone intravitreal implant to have some inflammation control onboard going into surgery.

If a patient received a long-acting steroid such as a fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant in one eye, then the anterior segment surgeon and I talk about prescribing an extended steroid taper. We inform the patient that we will have a low threshold for proceeding to an injection. If the inflammation in the first eye was attributable to intraoperative complications or increased manipulation, then the anterior segment surgeon and I discuss how we will manage the second eye if this situation arises again. If it does not and cataract surgery proceeds as planned, then a normal postoperative protocol may be followed.

CONCLUSION

Given the potential complexity of chronic inflammation after cataract surgery, patients often require targeted evaluation and therapy. When making a referral, it is helpful for the anterior segment surgeon to convey as much information as possible about the case, including preoperative and surgical details, symptoms, and the results of any tests and imaging. The possibility of endophthalmitis must be considered, but chronic postoperative inflammation is usually idiopathic. In most cases, there is time for the anterior segment surgeon and retina specialist to work collaboratively and ensure that the best decisions are being made for each patient.

1. Eliott D, Kim I, Yonekawa Y. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema (Irvine-Gass syndrome). EyeWiki. Updated May 31, 2022. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Pseudophakic_Cystoid_Macular_Edema_(Irvine-Gass_Syndrome)

2. Grzybowski A, Sikorski BL, Ascaso FJ, Huerva V. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema: update 2016. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1221-1229.

3. Taravati P, Lam DL, Leveque T, Van Gelder RN. Postcataract surgical inflammation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(1):12-18.