Doctors can face inquiries from patients after their insurance company rejects the bill for services the insurer deems not medically necessary. The patient, moreover, may decline to pay the deductible for these services or, if payment was already rendered, demand the money back. Worse, a complaint may be lodged with the State Board of Medicine, leading to a tribunal.

We have all experienced situations in which patients expressed nuanced and heartfelt disagreements about their treatment. Most times, the care the patient received was medically necessary and in their best interest because the doctor prioritized their welfare. Rarely, however, doctors put their interests before those of their patients and provide care that is outside of medical necessity but for which they are paid.

No surgeon wants to defend themselves against allegations of financial fraud in a court of law. The issue of medically unnecessary care was top of mind for me several years ago when my technician, Lenora, took my arm in between patients, pulled me aside, and asked me to keep an open mind. She had the same look on her face that my wife and kids had when they brought home our first puppy. Where I practice, technicians make notes on a cover sheet to give doctors background information on the next patient before we enter the room and look at the computer. The note on this patient read, “One-eyed patient in hospice on comfort care only with a cataract in her only eye.” The patient had end-stage cancer. She was racked with pain and was expected to live for less than a month.*

THE ANSWER WAS NO

To make sure that I kept an open mind, Lenora shooed away my scribe, closed the door, and settled in behind me to observe the patient’s examination. The patient was frail and seated in the exam chair. Her daughter and granddaughter were present in the room as well. My mind said there was no way in the world that I was going to operate.

The patient was in her mid-70s. She had lost the vision in her right eye to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy some years earlier. Moderate nuclear changes in the left eye were rapidly developing into a posterior subcapsular cataract owing to the systemic steroids in her chemotherapy. According to the patient’s medical record, her BCVA had been roughly 20/50 OS 6 months earlier, and it was now 20/400 at all distances and uncorrectable. The patient could not read or see the television.

As I read her chart, all I could think about were the risks posed by cataract surgery. At the earliest, surgery could take place in 10 days. How long would the patient survive after the procedure? How could I possibly justify cataract surgery as medically necessary?

AN OPEN MIND CAN BE A CHANGED MIND

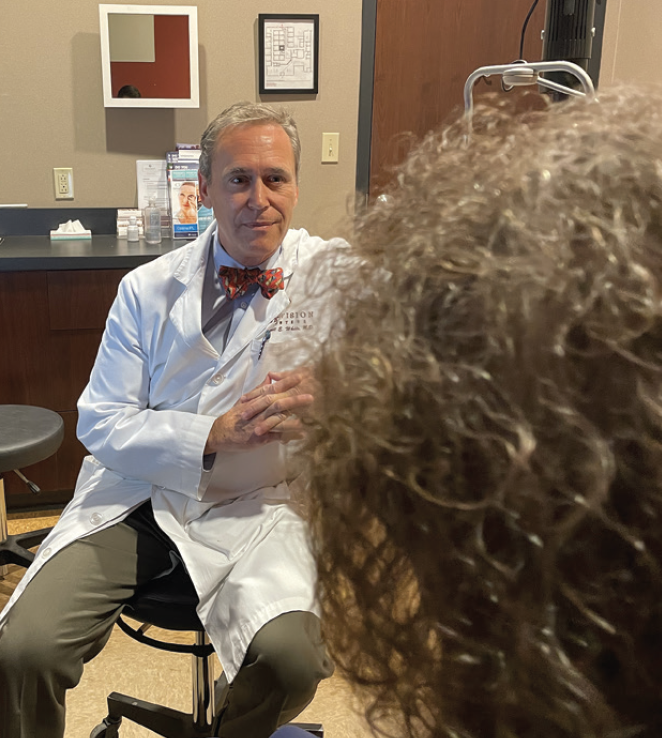

I had promised Lenora that I would listen and keep an open mind. I described to the patient and her family the challenges we faced (Figure). As gently as I could, I outlined the standards that could be violated if we proceeded with surgery, and I explained the complications that could occur. I then asked the patient why, with so little of her life remaining, she would choose to spend any of it undergoing and recovering from eye surgery.

Figure. Dr. White counseling a patient.

The patient answered, “All I have left now is my family. They are all here. They have all come to be with me. I hear their voices. I feel their arms around me, but I can’t see them. I don’t know who is with me unless they speak and tell me. I don’t want to get you in trouble. We will all understand if you say it can’t be done, but it would be the best gift to be able to see my family for as long as I am still here.”

Lenora had been right. I agreed to do the surgery. I selected an IOL power to give the patient good uncorrected intermediate visual acuity so that she could see, without glasses, her family gathered around her.

I would argue that most of the efforts to combat unnecessary care are about saving money. I therefore told the patient and her family that we would not charge her for surgery, although there might be a bill from the ambulatory surgery center and anesthesia group. When we explained the patient’s story to the administrators for those two entities, they decided not to charge her, either.

OUTCOME

One day after surgery, the patient had a manifest refraction of -1.25 D of sphere without cylinder in the left eye. Her best corrected distance visual acuity was 20/20 OS, and she could see clearly at roughly 4 feet—perfect for spotting incoming hugs. We decided that she could skip her 1-week visit to spare her more time in a doctor’s office. I thanked the patient and her family for reminding all of us at the practice what the meaning of necessary care really is, and all of us hugged the patient and her family before they left. I then found Lenora and thanked her, too.

The patient died peacefully exactly 1 week later, surrounded by a loving family she could see until the end.

*Author’s note: The patient and her family granted permission at the time of her care for the author to share the details of her case.