CASE PRESENTATION

In late 2018, after her optometrist suggested that she might have keratoconus, a 12-year-old girl presented with her mother for an evaluation. The patient was starting to experience some difficulty with her vision at school. Although she did not habitually rub her eyes, she had hay fever, and tarsal conjunctival papillae were evident. Her family history was negative for keratoconus.

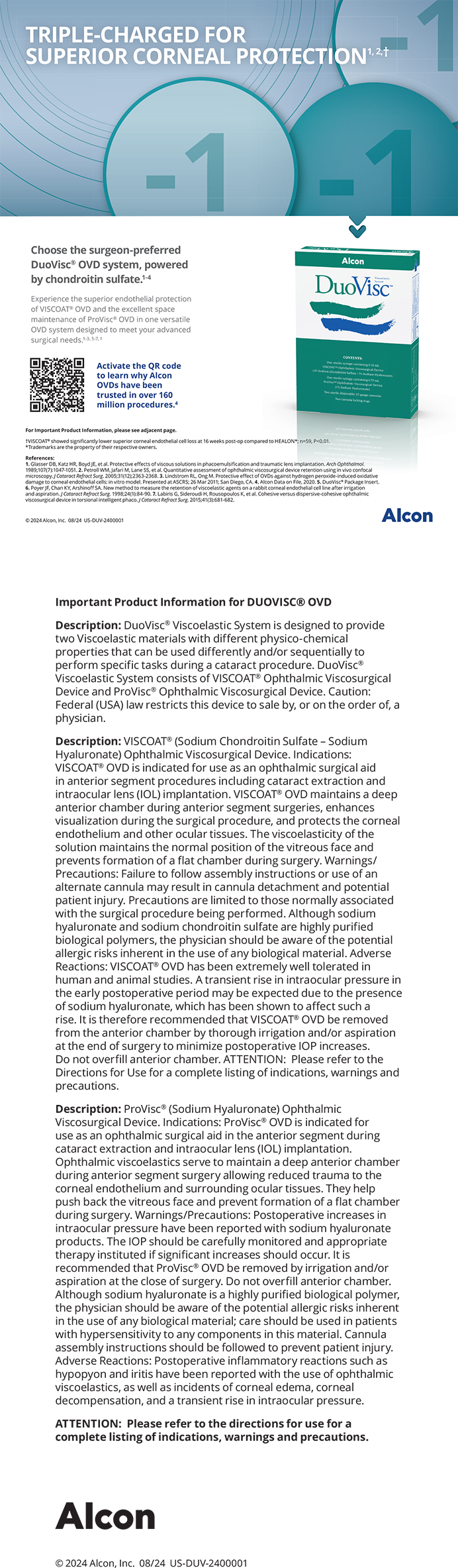

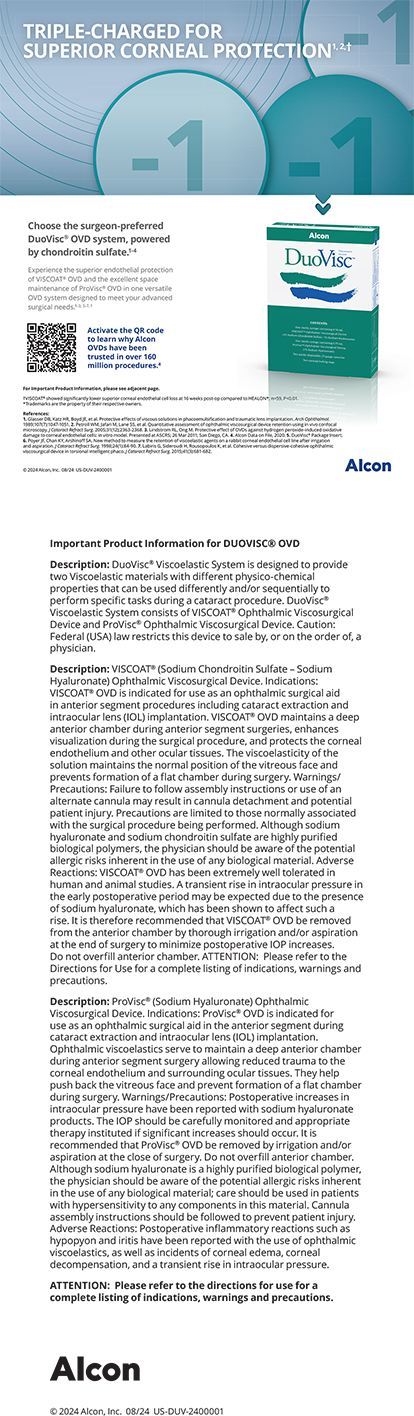

Upon examination, the patient’s BCVA was 6/6-1 with a manifest refraction of +0.50 -0.75 x 5º OD and 6/12 with a manifest refraction of +0.75 -0.25 x 145º OS. She did not accept higher cylinder for the left eye. Topography showed early keratoconic changes that were more significant in the left eye and associated thin pachymetry readings (Figure 1). Mild abnormality was noted on the Belin/Ambrósio Enhanced Ectasia Display (BAD) with the Pentacam (Oculus Optikgeräte; Figure 2). The rest of the examination was unremarkable. She had been wearing spectacles for approximately 1 year, and her refraction had recently changed.

Figure 1. Topography of the right (A) and left (B) eyes in 2018.

Figure 2. BADs for the right (A) and left (B) eyes in 2018.

How would you have proceeded in 2018? If the same patient presented today, would your approach to management differ?

— Case prepared by Abi Tenen, MBBS(Hons), FRANZCO

FARHAD HAFEZI, MD, PHD, FARVO

The right cornea shows mild asymmetry between the upper and lower anterior steepness, slightly reduced overall thickness, and a decentered thinnest point inferiorly with minimal posterior bulging—findings consistent with subclinical keratoconus. The left cornea displays more pronounced anterior ectasia, borderline thickness, and mild posterior elevation—findings consistent with manifest keratoconus.

In 2012, my group published the first large pediatric CXL study, which showed an 88% natural progression rate.1 Based on these findings, we proposed immediate CXL upon the detection of ectasia, without waiting for documented progression. In 2018, I would have confirmed biomechanical instability with the Corvis system (Oculus Optikgeräte) and treated both eyes with epithelium-off (epi-off) CXL using the Dresden protocol because I had found that children required the strongest form of CXL to prevent rapid disease progression.

Since 2019, I have used the MS-39 OCT/Placido topographer (CSO), which includes epithelial thickness mapping—an excellent indicator for early disease progression. The forthcoming second global keratoconus consensus confirms that 90% of corneal specialists now recommend immediate CXL for pediatric keratoconus upon diagnosis.

If the patient presented to my practice today, her right eye would undergo treatment using our ELZA epithelium-on (epi-on) accelerated CXL protocol, which offers efficacy comparable to that of standard epi-off CXL but is less invasive.2 The left eye would undergo treatment using our new high-fluence CXL protocol (10 J/cm2), which we have found to achieve Dresden-equivalent biomechanical strength in one-third the time.3

My current approach reflects an evolution from conventional to optimized, individualized CXL strategies for pediatric keratoconus management.

DAVID R. HARDTEN, MD, FACS

Keratoconus is a progressive, noninflammatory ectatic disorder of the cornea that can lead to significant visual impairment and functional disability if left untreated. Although patients are not born with keratoconus, early signs such as inferior steepening, asymmetry, and the topographic changes seen in this patient are predictive of disease progression, particularly in someone so young.

Early intervention is critical. CXL arrests keratoconus progression by strengthening corneal biomechanical stability. The earlier the procedure is performed, the better it preserves vision and delays or avoids the need for corneal transplantation. For this patient, I would recommend bilateral CXL.

It is also essential to address modifiable risk factors contributing to keratoconus progression. Atopic disease and allergic eye rubbing are key mechanical stressors on the cornea. Aggressive management of the patient’s ocular allergy and behavioral counseling would therefore be initiated to prevent eye rubbing. Her typical sleep posture would also be explored. Prone or side sleeping with pressure on the eyes, sometimes related to undiagnosed sleep apnea (particularly in older patients), can exacerbate keratoconus progression.

In the United States, where I practice, the iLink system (Glaukos) is a US FDA-approved option for CXL. Epioxa (Glaukos) has also recently gained approval. For the past 10 to 15 years, I have typically treated the eye with more severe keratoconus first. I have found that most patients can either resume wearing glasses or be fitted for scleral contact lenses within about a month of treatment. The second eye is scheduled for CXL approximately 2 months after the first.

For patients with advanced keratoconus and significant visual impairment that is not adequately corrected with glasses or contact lenses, I may consider adjunctive procedures such as the placement of allogenic corneal tissue segments (CorneaGen) in the anterior cornea to improve corneal shape.4 This technology was not available in 2018. Intacs (CorneaGen) were, but I would not have recommended them. Given the patient’s age, early disease stage, and probable tolerance of scleral contact lenses, I would proceed with CXL alone at this time.

A. JOHN KANELLOPOULOS, MD

In my opinion, a careful review of the Scheimpflug images provided for the left eye reveals clear signs of keratoconus—inferior steepening as well as irregular anterior and posterior elevation. Pachymetry shows a decentered area of corneal thinning and a noncircular area of “steps” that move from central thinning to peripheral thickening and are decentered from the cornea’s vertex, as defined by angle kappa on the x-axis, which is 360 µm.

I consider the right eye to be slightly abnormal as well. The thinnest part of the cornea is 486 µm, and it shows the same qualitative and quantitative signs of an irregular corneal thickening gradient and shape on Scheimpflug imaging as evident in the left eye—truncation of the astigmatism, scissoring, irregular astigmatism that is greatest inferiorly, and an irregular anterior and posterior elevation map. More importantly, the thickness maps for the right eye show significant inferotemporal skewing of the thinnest point of the cornea that does not match the vertex, as defined by angle kappa. The x-axis of angle kappa is only 210 µm; the thinnest point of the cornea is far more temporal than that.

On the BAD for each eye, the increase in percentage thickness from the center to the periphery of the cornea is outside the normal range for a patient her age. In 2018, I would have ordered epithelial mapping to help determine how progressive the keratoconus in each eye was.

Next, a do-it-yourself face mask, with two soft sleep masks sutured around eye shields, would have been made (scan the QR code to see how to fashion one). I would have asked the patient to wear the face mask at night to prevent her from rubbing her eyes during sleep, which in my experience is the main driver of keratoconus progression, along with possible daytime rubbing. I also would have evaluated her mother and, if possible, her father to determine which of them was predisposed to keratoconus.5 This approach would have allowed a screening process to be created for the appropriate side of the family, with an emphasis on teenagers.

I would have offered CXL, probably an epi-on approach. Although less robust than epi-off CXL, the epi-on approach is easier for children her age to handle and is associated with less morbidity. If the family had opted against intervention, I would have recommended regular observation at least every 6 months and advised her to avoid rubbing her eyes, especially while sleeping.

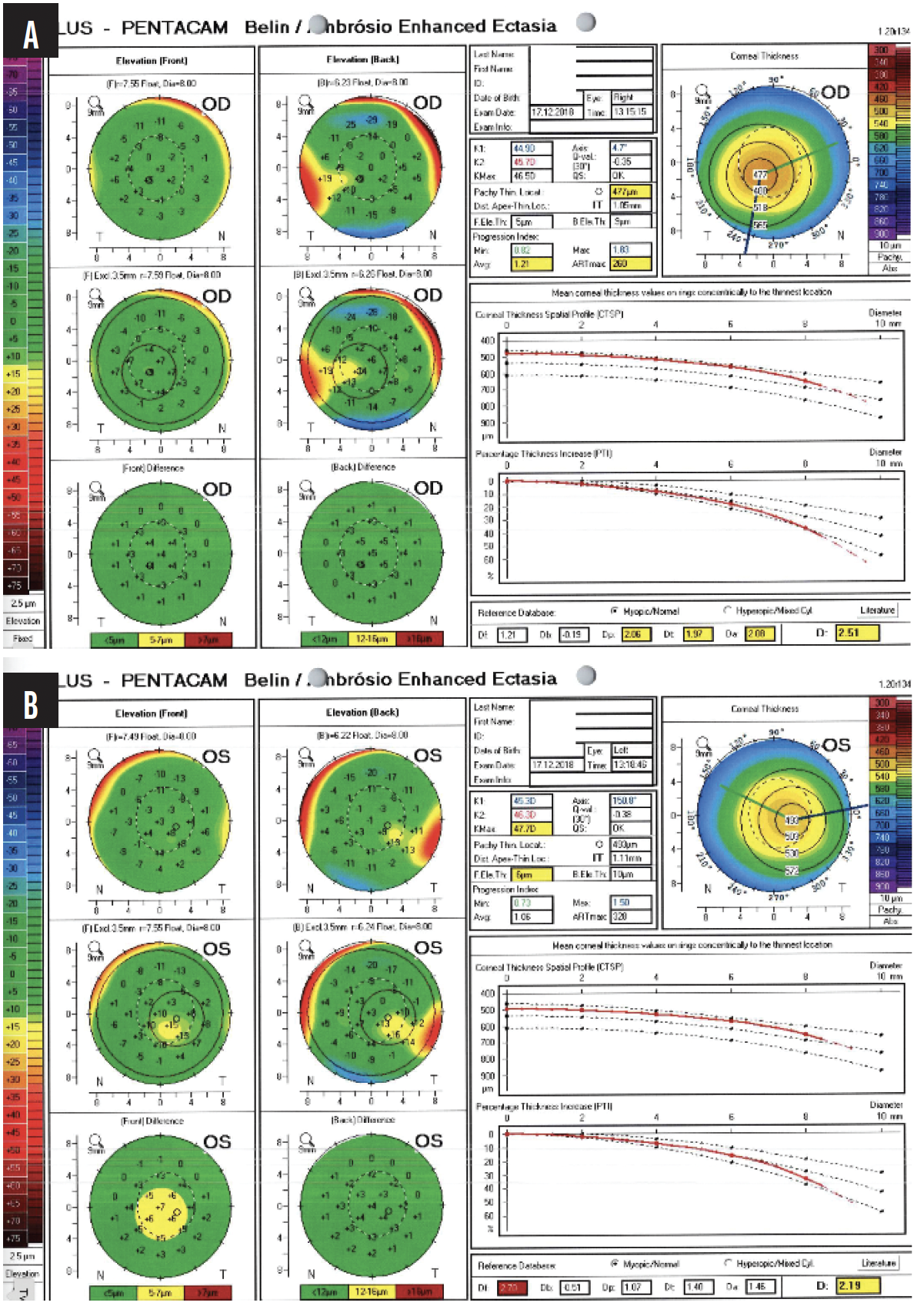

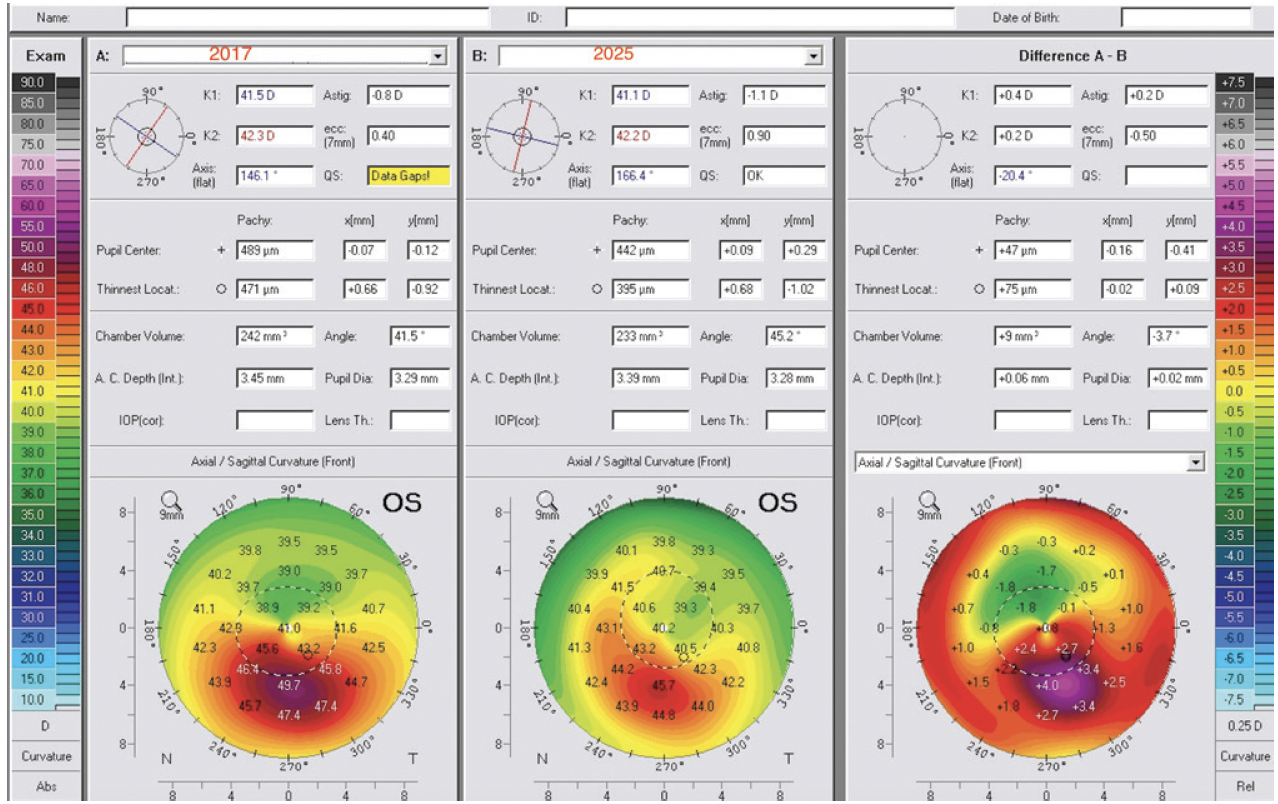

These clinical strategies, which I have taught at courses held at major meetings for more than 20 years, continue to help me navigate the management of patients with keratoconus and their families. A case of mine from 2017 illustrates the approach. A 16-year-old boy presented with symptomatic keratoconus in his left eye. Progressive irregular corneal changes were detected with the Pentacam in the left eye along with milder changes in the right eye. The left eye underwent topography-guided therapeutic reshaping and epi-on CXL using the Athens protocol (Figure 3).6 The right eye was treated with transepithelial CXL (Figure 4) with the Mosaic CXL device (Glaukos).

Figure 3. Dr. Kanellopoulos shares a similar case from 2017 involving a 17-year-old boy. The left eye underwent CXL using the Athens protocol. Measurements for the left eye are shown: preoperative (left), 8 years postoperatively (middle), and the change represented by the difference between them (right).

Figures 3–7 courtesy of A. John Kanellopoulos, MD

Figure 4. The right eye of the patient shown in Figure 3 underwent transepithelial CXL using the Parcel and Vibex Xtra riboflavin solutions (Glaukos) and CXL (30 mW/cm2 for 4 minutes for a total of 7.2 J of UV energy delivered). The changes that occurred from 2017 to 2025 in topography (A) and keratometric indices (B) are shown.

Eight years following treatment, the patient is a neurosurgery resident in the United States. His uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) is 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. Both CXL techniques resulted in stabilization; the Athens protocol drastically reversed ectasia-related corneal irregularity in the left eye, as reported in dozens of peer-reviewed publications on similar cases, some with more than 10 years of follow-up.5 Interestingly, the transepithelial higher-fluency CXL procedure on the less affected right eye offered not only long-term stability but also some signs of mild normalization on tomography and a slight keratometric improvement (Figure 4B).

Just a month before this writing, the 11-year-old daughter of a patient on whom I had performed CXL using the Athens protocol 10 years earlier presented with advanced stage 2 keratoconus in both eyes and severely reduced visual function (Figure 5). After a detailed discussion with the patient’s parents, she underwent CXL using the Athens protocol in one eye, and her second eye is scheduled for the same treatment early this year (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 5. The 11-year-old daughter of a patient on whom Dr. Kanellopoulos performed CXL using the Athens protocol 10 years ago recently presented to his clinic with 20/50 UDVA OU and 20/20 CDVA OU. Measurements with the Pentacam revealed advanced keratoconus in both eyes (A). Anterior segment OCT showed progressive, advanced keratoconus and epithelial remodeling in each eye (B).

Figure 6. Sequential laser ablation of the epithelium using the Wavelight EX500 Laser System (Alcon) was performed on both eyes of the patient shown in Figure 5. The central cornea underwent 8-second topography-guided treatment to reduce irregularity, leaving -2.50 D of myopia. Next, a 12-second +2.50 D hyperopic treatment was performed to complete epithelial removal. The goal was to reduce the duration of transepithelial treatment given the patient’s age and to preserve as much tissue as possible. CXL was then performed with a power of 6 mW/cm2 and a duration of 15 minutes.

Figure 7. Preoperative measurements (left), postoperative measurements (middle), and the difference between them (right) are displayed for the patient shown in Figures 5 and 6. Treatment normalized and stabilized the cone. Postoperatively, her UDVA was 20/30 OU, and her CDVA was 20/20 OU.

WILLIAM B. TRATTLER, MD

Children with keratoconus are at high risk of disease progression. Based on my experience, CXL should be strongly recommended once keratoconus has been diagnosed. This 12-year-old patient has already experienced vision loss. Both eyes exhibit inferior steepening and abnormal BAD scores. Both in 2018 and today, I would perform CXL on both eyes because the procedure would likely prevent further vision loss. Additionally, many patients experience an improvement in corneal shape and vision months and years following CXL.7

In a similar case, a 15-year-old boy presented to my practice in July 2021. His right eye had significant keratoconus, and his BCVA in that eye had decreased. The left eye had no obvious asymmetry, although the shape could have been classified as an early truncated bow tie (Figure 8). The BAD score was normal in the left eye. The patient’s family elected treatment for the right eye and observation for the left eye. He was lost to follow-up until April 2025. Upon examination, the right eye had remained stable following CXL. The left eye, however, had developed significant keratoconus, and his BCVA in that eye had decreased (Figure 9). The patient underwent CXL in the left eye in June 2025.

Figure 8. Dr. Trattler shares a case from 2021 involving a 15-year-old boy. The patient’s BCVA had decreased in the right eye, and significant keratoconus is evident. The left eye has 20/20 BCVA and no obvious asymmetry, although in retrospect, an early truncated bow tie is visible.

Figures 8 and 9 courtesy of William B. Trattler, MD

Figure 9. The right eye of the patient shown in Figure 8 underwent CXL in 2021, and he was lost to follow-up. When he returned in 2025, the right eye had remained stable. The untreated left eye, however, had developed significant keratoconus, and the patient’s BCVA in that eye had decreased.

Based on cases like this one, CXL has a high likelihood of stabilizing the cornea and preventing vision loss in children and young adults with keratoconus for whom the risk of progression is high. The risk-benefit profile appears to be stronger for epi-on than epi-off CXL in all patient age groups because the risk of corneal haze and infection is lower with epi-on versus epi-off CXL.7 The center where I practice first performed epi-on CXL with pulsed light in 2010 as part of the CXLUSA clinical trial, and this technology was a precursor to EpiSmart (Epion Therapeutics). Our experience has been very positive, with less than a 1% need for repeat treatment at our center. Additionally, Glaukos recently received US FDA approval for its version of epi-on CXL, Epioxa, which should soon become commercially available in the United States, where I practice.

WHAT I DID: ABI TENEN, MBBS(HONS), FRANZCO

I immediately prescribed a preservative-free topical lubricant to reduce the allergen load because, although the patient’s eyes did not itch and she was not rubbing them, signs of hay fever were present. In 2018, I had been performing CXL for 10 years and had already recognized within my own practice a role for treating young patients as soon as possible because waiting to prove progression only achieved a worse visual prognosis. My opinion was unpopular at the time. I discussed the pros and cons of CXL versus observation with the patient’s mother, and she opted to proceed with treatment.

Bilateral epi-on CXL was performed a few months after the patient’s initial presentation to my practice. A compounded hypotonic riboflavin 0.1% solution was administered, followed by 30 minutes of UV exposure—an adaptation of the Dresden protocol (3 mW/cm2). This technique was my preference for young adolescents.

Three months following treatment, topography showed flattening, and the patient’s visual acuity had improved. More striking was the continued flattening on topography and improvement in her visual acuity observed during the years thereafter.

In early 2025, at 18 years of age, the patient presented for a follow-up visit with her mother. The patient had been diagnosed with celiac disease in the intervening years, and she was studying software engineering at a university. Her UDVA was 6/6 OU and 6/4.8 with both eyes open. Her corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) was 6/4.8 with a manifest refraction of +0.50 -0.50 x 180º OD and 6/4.8 with a manifest refraction of +0.50 -0.50 x 160º OS. She no longer wore her glasses often. Topography was relatively regular (Figure 10), and pachymetry remained thin but stable. Updated diagnostic images are not provided, because no comparison data from 2018 are available.

Figure 10. Topography of the right (A) and left (B) eyes of the patient shown in Figures 1 and 2 in 2025.

Courtesy of Abi Tenen, MBBS(Hons), FRANZCO

If this patient presented to my clinic today, my advice would be essentially the same. Updates would include an assessment with a modern anterior segment OCT device and epi-on CXL performed using the KXL System (Glaukos), with its proprietary riboflavin formulation and accelerated UV light delivery.

1. Chatzis N, Hafezi F. Progression of keratoconus and efficacy of pediatric [corrected] corneal collagen cross-linking in children and adolescents. J Refract Surg. 2012;28(11):753-758.

2. Lu NJ, Torres-Netto EA, Aydemir ME, et al. A transepithelial corneal cross-linking (CXL) protocol providing the same biomechanical strengthening as accelerated epithelium-off CXL. J Refract Surg. 2025;41(7):e724-e730.

3. Abrishamchi R, Abdshahzadeh H, Hillen M, et al. High-fluence accelerated epithelium-off corneal cross-linking protocol provides Dresden protocol-like corneal strengthening. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2021;10(5):10.

4. Greenstein SA, Yu AS, Gelles JD, Eshraghi H, Hersh PS. Corneal tissue addition keratoplasty: new intrastromal inlay procedure for keratoconus using femtosecond laser-shaped preserved corneal tissue. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2023;49(7):740-746.

5. Kanellopoulos AJ. Clinical prevalence of familiar association in keratoconus (KCN): tomographic evaluation of KCN patient parents. Poster presented at: 9th EUCornea Congress; September 21-22, 2018; Vienna, Austria.

6. Kanellopoulos AJ. Combined photorefractive keratectomy and corneal cross-linking for keratoconus and ectasia: the Athens protocol. Cornea. 2023;42(10):1199-1205.

7. Epstein RJ, Belin MW, Gravemann D, Littner R, Rubinfeld RS. EpiSmart crosslinking for keratoconus: a phase 2 study. Cornea. 2023;42(7):858-866.