As the number of IOLs available to us grows, so does the opportunity for patients to achieve excellent visual outcomes. Technological advances bring exciting new possibilities for correcting presbyopia, improving quality of vision, and providing spectacle independence, but these advances also bring challenges. How should dysphotopsias be resolved? How does cost factor into the adoption of premium IOLs? Which strategies are effective for educating patients about their IOL choices? This article examines some of the pros and cons of the latest IOLs.

PROS

No. 1: Greater refractive accuracy. The refractive accuracy of cataract surgery depends on accurate biometry measurements, particularly when a presbyopia-correcting IOL is chosen. Fortunately, preoperative diagnostic technology has advanced at the same rate as IOL technology. Incorporating OCT-based biometry and tomographic measurements such as total corneal power has led to faster and more reliable acquisition of preoperative measurements for cataract surgery.

In the past, surgeons used a combination of regression-based or theoretical formulas when an eye had atypical biometry values. For example, the Hoffer Q formula tended to be more accurate when the axial length was short, whereas the SRK/T formula was generally more accurate for eyes with longer axial lengths.1 Recently, the Barrett Universal II and Kane formulas have been shown to be comparable or superior to other IOL formulas regardless of biometry value; the predicted postoperative spherical equivalent was reported to be within ±1.00 D in more than 98% of patients in whom these formulas were used.2,3

Postoperative decentration of the IOL nonconcentric with the subject-fixated coaxially sighted corneal light reflex may increase the risk of dysphotopsia, coma, and patient dissatifaction.4 Preoperative measurements of chord mu, pupil tracking, and ray-tracing aberrometry and intraoperative measurements of IOL centration with computer-assisted devices may help to ensure proper lens alignment and centration (check below to watch a related video).5,6

No. 2: Customized vision. Determining which corrective strategy will best satisfy a given patient warrants careful consideration. Ophthalmologists must consider the individual’s hobbies, desire for spectacle independence, and visual needs.

Nearly 2 billion people in the world have presbyopia, and more than half of them have impaired near vision.7 The success of a mini-monovision or monovision strategy in cataract surgery is limited by the degree of anisometropia that the patient can tolerate. Presbyopia-correcting IOLs may be a better option for individuals who desire a wide range of acuity for near, intermediate, and distance targets.

Presbyopia-correcting lenses are categorized as extended depth of focus, multifocal, and accommodating, and there can be overlap among these categories (hybrid designs). Long-term data are needed to determine who are the best candidates for each category of IOL.

Laser and light-adjustable lens technology has also been developed to allow fine-tuning of the refractive outcome of cataract surgery. A femtosecond laser (Perfect Lens) is being developed to modify the power, shape, and toricity of an IOL in vivo.8,9 This technology is still in the developmental pipeline but holds great promise. Early studies suggest that it can address refractive surprises after cataract surgery with a high degree of repeatability.9 The Light Adjustable Lens (RxSight) is FDA approved and available in spherical powers of -2.00 to +2.00 D and cylindrical powers of -0.75 to -2.00 D. The powers can be adjusted with the application of UV light after cataract surgery.10,11

CONS

No. 1: Chair time. Henry Kissinger, a former US Secretary of State, once said, “The absence of alternatives clears the mind marvelously.” The expanded roster of IOL categories and implants can confuse doctors and patients. Cataract surgeons must have a strong understanding of IOL designs and patient selection to maximize postoperative refractive accuracy and patient satisfaction. They must also be able to set realistic expectations for patients, clearly describe out-of-pocket expenses, and explain why a certain IOL is being recommended to optimize the patient experience.12 Studies have shown that having patients watch educational videos that describe cataract surgery and the differences between IOLs as part of the preoperative consultation process can increase postoperative patient satisfaction, premium IOL conversion rates, and patient understanding of the risks and benefits of cataract surgery.13,14 Most practices have counselors to handle the preoperative consultation, and more practices are moving toward precounseling to further streamline the process.15

The importance of informed consent in ophthalmology cannot be overemphasized. As technology becomes more sophisticated and IOL options expand, more time must be spent educating patients.

No. 2: Cost. In the United States, most insurance plans cover the cost of cataract surgery and the implantation of a monofocal IOL.16 Out-of-pocket expenses, however, can vary widely if an individual chooses to receive astigmatism correction, a premium IOL, and/or laser cataract surgery. On average, the additional out-of-pocket cost of toric and multifocal IOLs is $1,500 and $2,500 per eye, respectively. The approximate cost of laser cataract surgery is $1,500 per eye.17 Recent studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of premium IOL implantation and reported that multifocal IOLs can improve patient quality of life by increasing their spectacle independence.18,19 The added value by comparison is a special opportunity for vision correction for a lifetime.

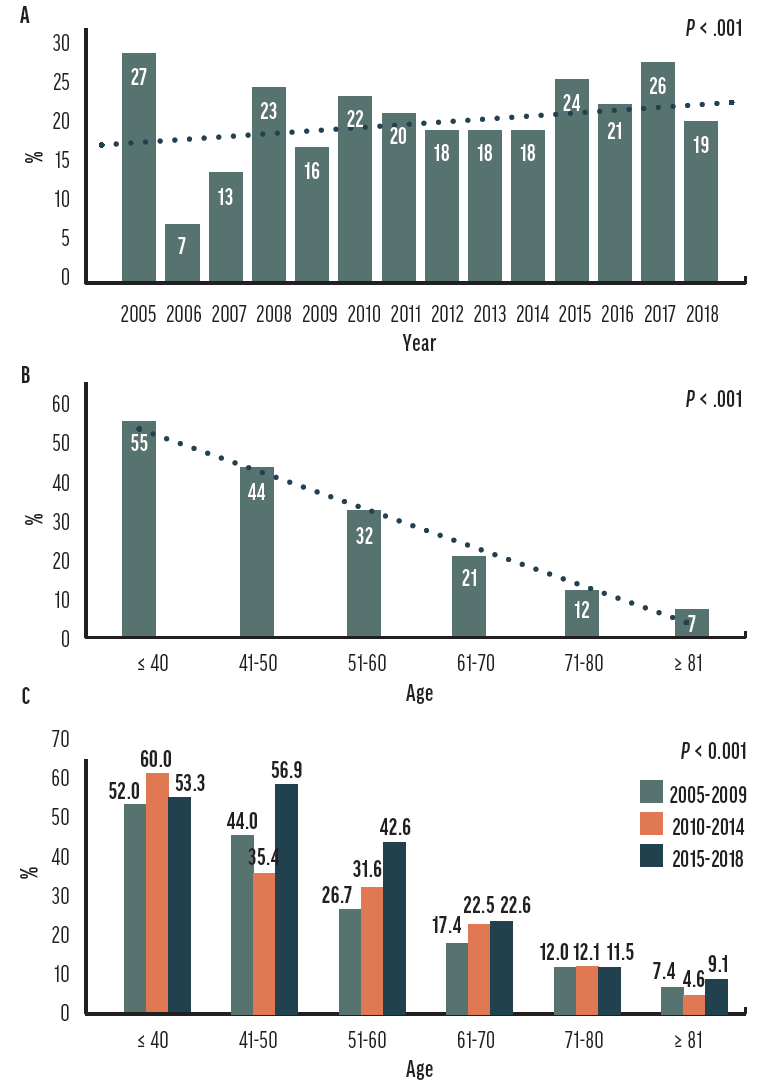

No. 3: Contraindications and side effects. Multifocal IOLs are not suitable for everyone. Preexisting ocular pathology such as epiretinal membrane, irregular astigmatism, ocular surface disease, glaucoma, macular degeneration, amblyopia, and strabismus can increase the risk of unfavorable outcomes postoperatively. With the advent of extended depth of focus IOLs, patients with milder forms of concomitant pathology may still pursue presbyopia correction. This issue and concerns about postoperative dysphotopsias and sometimes unpredictable postoperative neural adaptation have led some surgeons to abandon certain premium IOLs. Moreover, older patients may be more willing than younger patients to wear spectacles and thus less likely to pay the out-of-pocket fee for multifocal IOLs (Figure).20

Figure. The overall trend in multifocal IOL adoption from 2005 to 2018 (A). The trend in multifocal IOL adoption across different patient age groups (B). The change in adoption rates was most significant in the younger adult group (C). Adapted from Chang SW, Wu WL.20

CONCLUSION

Patient expectations continue to rise. Improvements in IOL design, the availability of expanded IOL options, and advances in perioperative tools can help surgeons to meet these demands. Today, surgeons have a multitude of IOL options to consider to better customize vision to patient needs and candidacy and to determine the right mix of IOLs for their practice.

1. Aristodemou P, Knox Cartwright NE, Sparrow JM, Johnston RL. Formula choice: Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, or SRK/T and refractive outcomes in 8108 eyes after cataract surgery with biometry by partial coherence interferometry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(1):63-71.

2. Connell BJ, Kane JX. Comparison of the Kane formula with existing formulas for intraocular lens power selection. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2019;4(1):e000251.

3. Melles RB, Holladay JT, Chang WJ. Accuracy of intraocular lens calculation formulas. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(2):169-178.

4. Xu J, Zheng T, Lu Y. Effect of decentration on the optical quality of monofocal, extended depth of focus, and bifocal intraocular lenses. J Refract Surg. 2019;35(8):484-492.

5. Chang DH, Waring GO 4th. The subject-fixated coaxially sighted corneal light reflex: a clinical marker for centration of refractive treatments and devices. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(5):863-874.

6. Singh IP. Use of CALLISTO eye to verify the centration of a multifocal lens exchange. Eyetube. 2018. Accessed January 11, 2022. eyetube.net/videos/use-of-callisto-eye-to-verify-the-centration-of-a-multifocal-lens-exchange

7. Fricke TR, Tahhan N, Resnikoff S, et al. Global prevalence of presbyopia and vision impairment from uncorrected presbyopia: systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(10):1492-1499.

8. Mercer RN, Milliken CM, Waring GO 4th, Rocha KM. Future trends in presbyopia correction. J Refract Surg. 2021;37(S1):S28-S34.

9. Nguyen J, Werner L, Ludlow J, et al. Intraocular lens power adjustment by a femtosecond laser: in vitro evaluation of power change, modulation transfer function, light transmission, and light scattering in a blue light-filtering lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(2):226-230.

10. Schojai M, Schultz T, Schulze K, Hengerer FH, Dick HB. Long-term follow-up and clinical evaluation of the light-adjustable intraocular lens implanted after cataract removal: 7-year results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46(1):8-13.

11. Moshirfar M, Wagner WD, Linn SH, et al. Astigmatic correction with implantation of a light adjustable vs monofocal lens: a single site analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12(7):1101-1107.

12. Nijkamp MD, Nuijts RM, Borne B, Webers CA, van der Horst F, Hendrikse F. Determinants of patient satisfaction after cataract surgery in 3 settings. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26(9):1379-1388.

13. Vo TA, Ngai P, Tao JP. A randomized trial of multimedia-facilitated informed consent for cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1427-1432.

14. Wisely CE, Robbins CB, Stinnett S, Kim T, Vann RR, Gupta PK. Impact of preoperative video education for cataract surgery on patient learning outcomes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:1365-1371.

15. Nash M. Prepare patients for cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Professional. 2019;8:18-20.

16. Maxwell WA, Waycaster CR, D’Souza AO, Meissner BL, Hileman K. A United States cost-benefit comparison of an apodized, diffractive, presbyopia-correcting, multifocal intraocular lens and a conventional monofocal lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(11):1855-1861.

17. Mandel MR, medical reviewer. How much does cataract surgery cost? Better Vision Guide. Updated April 21, 2021. Accessed January 7, 2022. www.bettervisionguide.com/cataract-surgery-cost

18. Hu JQ, Sarkar R, Sella R, Murphy JD, Afshari NA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of multifocal intraocular lenses compared to monofocal intraocular lenses in cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;208:305-312.

19. Maxwell WA, Waycaster CR, D’Souza AO, Meissner BL, Hileman K. A United States cost-benefit comparison of an apodized, diffractive, presbyopia-correcting, multifocal intraocular lens and a conventional monofocal lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(11):1855-1861.

20. Chang SW, Wu WL. Age affects intraocular lens attributes preference in cataract surgery. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2021;11(3):280-286.