Iris prolapse is not uncommon in cataract surgery. This complication sometimes significantly affects visual outcomes, and, when it does, it leaves both the patient and the surgeon unhappy. The best way to deal with iris prolapse, of course, is to prevent it. When the iris prolapses despite your best efforts, however, several key management decisions make the difference between a satisfactory and an unsatisfactory outcome.

RISK FACTORS

A heightened awareness of when iris prolapse is more likely to occur will serve you well. Risk factors include the following:

- A shallow anterior chamber;

- Medical therapy that predisposes a patient to intraoperative floppy iris syndrome;

- A short tunnel incision, usually associated with a more peripheral internal entry site to the tunnel; and

- Posterior pressure from native anatomy, an intumescent lens, straining during surgery, a suprachoroidal hemorrhage, or a suprachoroidal effusion.

Each of these factors increases the likelihood that the iris will approach the incision(s) and the pressure gradient will rise from the anterior chamber to the incision. A key point: Without both proximity and a pressure gradient, iris prolapse will not occur.

PREVENTION

There are several steps you can take to reduce the likelihood of iris prolapse. These measures can be applied to your routine technique, but they are certainly worth entertaining for higher-risk cases.

Anatomy. When an eye has an extremely shallow anterior chamber (as in nanophthalmos) or another anatomic issue that creates posterior pressure, ameliorate the issue a priori if possible. In the absence of contraindications, an intravenous injection of mannitol is useful to reduce vitreous volume. Reverse Trendelenberg positioning and general endotracheal anesthesia with paralytics can also mitigate posterior pressure caused by patient anatomy.

Incision. The cornea is ovoid and longer horizontally, and therefore operating temporally permits the creation of a longer tunnel. It also allows you to enter the eye far enough from the apex of the cornea to prevent distortion. A long (ideally square) tunnel is important, but even more important for preventing iris prolapse is for the internal entry point to be far enough forward in the anterior chamber that there is some space between the peripheral iris and internal wound and that the entry is located at least 1.5 mm from the iris insertion. This is true both for primary incisions and paracenteses. You may choose to elongate your usual paracentesis in a high-risk eye.

OVD. Be judicious in your use of OVD. Placing too great an amount in the eye can overpressurize the anterior chamber. When you go to place the phaco handpiece in the eye, the wound will be at atmospheric pressure, and some of the OVD will flow out of the wound. According to the Bernouili principle, the iris will follow and will be drawn into the wound. This is more common with dispersive than cohesive OVDs, but when OVD starts to exit the wound, expect the iris to follow. Fill the anterior chamber with just enough of an OVD to maintain space.

Fluidics. A common time for the iris to prolapse is when the phaco or I/A handpiece is removed from the eye. The anterior chamber pressure is high at this point. As the handpiece is removed, the wound opens, and fluid egresses from the wound, with the iris following just behind. This is an entirely preventable event. Some surgeons’ instinct is that the iris will remain farther from the wound if the chamber stays deep, but this is not the case. If the irrigation is discontinued and the handpiece is left in place in the eye until the chamber shallows, the IOP will decrease, the pressure gradient will vanish, and prolapse will not occur.

MANAGEMENT

Once the iris prolapses, avoid the temptation to stuff it back in the eye. Unless or until the factor(s) that caused the prolapse have been remediated, the iris will prolapse repeatedly out of the wound.

Reduce the anterior chamber pressure. Before the iris can be reposited, the anterior chamber pressure must be brought down nearly to zero. This can be accomplished by using a 27-gauge cannula attached to a 3-mL syringe half-filled with balanced salt solution to aspirate aqueous fluid, OVD, or soft cortex from the chamber via a paracentesis site until the pressure is low. Attempts to force the iris back into the eye against a pressure gradient in the opposite direction are futile. If the iris begins to prolapse where the cannula is placed into a paracentesis, it is advisable to create a fresh paracentesis with a more anterior internal entry point.

Tapping the external wound. Use pressure gradients to your advantage. After anterior chamber pressure is brought to zero, gently tapping on the external surface of the corneal tunnel creates a higher pressure within the wound, and the iris drops back into the anterior chamber without your even touching it (scan the QR code now to watch this technique). This can prevent damage to the iris stromal tissue, sphincter muscle, and iris pigment epithelial loss, the most common reasons for an unsatisfactory outcome after iris prolapse.

Pull instead of push. If the iris seems to be stuck in the wound and does not respond to external tapping (no contact with the iris), the iris can be pulled back into the anterior chamber. It is important to pull rather than push the tissue. Pushing in the iris from the same incision from which it prolapsed has the highest likelihood of damaging the stroma, sphincter, and iris pigment epithelium. Pulling the iris back in from a separate incision minimizes those risks.

Cannula sweep technique. Once anterior chamber pressure has been brought to near zero, create a fresh paracentesis 30º to 80º away from the prolapse in a location that is convenient for your dominant hand. The tip of the cannula is placed peripheral to the internal entry of the wound and under the wound so that the tip is peripheral to the entire area of prolapse. The cannula is gently and slowly swept centripetally, and the prolapsed iris is gently pulled out of the wound.

Forceps technique. A transcameral microforceps can be used to gently grasp the iris internally and gradually pull the iris tissue centripetally until the prolapse resolves. This technique is decidedly not ergonomic. Be careful not to pull too hard or too far that an iridodialysis is created.

Iridotomy technique. In extremely rare instances, OVD or fluid becomes trapped under the subincisional iris. In this situation, prolapse may not be readily treated with the cannula sweep or forceps techniques. Creating a small radial snip in the billowed parachute of the prolapsed iris tissue allows the OVD or fluid to escape. The prolapsed iris can then be reposited with the cannula sweep or forceps technique. Repairing the radial iridotomy later with a single suture is much easier than reconstituting macerated tissue.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Completing the case without recurrent prolapse. Once iris prolapse has occurred, it is extremely likely to recur if the precipitating factors have not changed. If the wound was an underlying factor, it is wise to close it and create a fresh incision in another meridian. (Editor’s note: For more on incisions, see the article, “An Irregular Main Incision.”) If fluidics or OVD use was to blame, then it is advisable to eliminate the pressure gradient by optimizing the amount of OVD used and shallowing the chamber before removing the handpieces. Sometimes, placing a small dollop of cohesive OVD just over the iris leaflet in this area creates a nice cushion. Keep in mind that the amount of OVD should not increase IOP.

If the iris has frayed in the subincisional area, the placement of one or more flexible iris retractors, one of which is located under or near the incision, helps to prevent repeated prolapse or aspiration of frayed iris tissue during surgery. Rings that stent the pupillary aperture are rarely helpful in this setting.

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Rarely, the origin of iris prolapse is an acute suprachoroidal hemorrhage. If this pathology is suspected, the anterior chamber pressure should not be reduced, the OVD should not be removed, and the iris should not reposited. Secure the wounds, postpone addressing the iris issues, and complete the anterior segment procedure at a later time when the acute, eye-threatening danger of a suprachoroidal hemorrhage has been mitigated. When, if, and how to drain a suprachoroidal hemorrhage are covered in the article, “Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage.”

REPAIRING THE DAMAGE

A wide variety of sequelae can follow iris prolapse:

- (Small or large) transillumination defects;

- Focal sphincter atrophy;

- (Mild or significant) stromal atrophy;

- Iridodialysis;

- A misshapen or discolored pupil; and

- Cystoid macular edema.

Some of these problems can create significant photic phenomena, a reduction in Snellen acuity, and contrast-related symptoms. Other components negatively affect the patient’s perception of their physical appearance. Several techniques can be employed to remediate damaged iris tissue, both functionally and cosmetically.

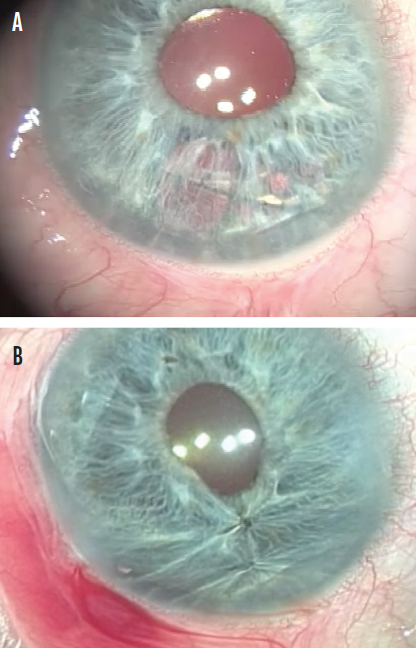

Iris oversewing. Oversewing the healthy tissue to either side of the defect may be all that is required for small defects and transillumination defects (Figure 1). For larger defects, the advisability of oversewing depends on the stretchiness of the iris tissue. The technique can result in cheese wiring, bleeding, and iridodialysis, and the pupil may become distorted or off-center.

Figure 1. Transillumination defect following iris prolapse (A) and after repair by oversewn sutures (B).

Repair can be attempted at the completion of a case, but it is often deferred depending on unique patient factors, the surgeon’s comfort level and skill set, catecholamine levels, and whether symptoms develop.

Contact lenses. Specialty contact lenses with an opaque periphery can limit how much light enters through damaged iris tissue, and some of these lenses improve cosmesis. Of course, contact lens management becomes a daily responsibility.

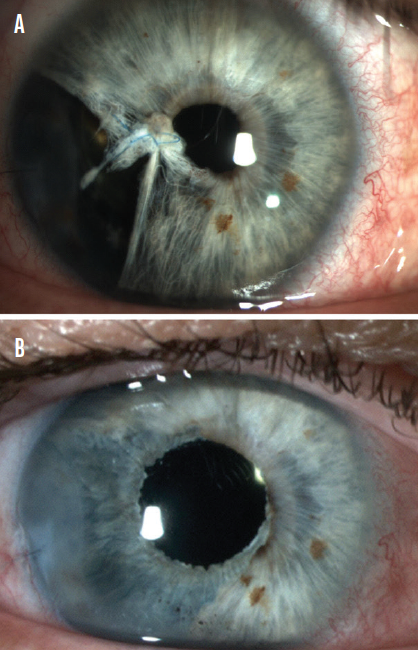

Iris prosthesis. If the damage cannot be oversewn easily and contact lens use is either impractical, ineffective, or undesirable, placement of an iris prosthesis behind the residual native iris tissue can markedly improve symptoms and, depending on the type of device used, may improve cosmesis (Figure 2). Various iris prostheses are available worldwide; some devices are black, some are available in a limited color palette, and some are color-matched to an index photograph of the eye. Selection depends on patient anatomy and device availability.

Figure 2. In this case, iris damage following iris prolapse during cataract surgery and attempted repair resulted in iridodialysis. Upon referral (A) and after placement of a custom, flexible-iris prosthesis (B).

Patient anatomy also dictates whether the device is placed within the capsular bag—ideal if the capsulorhexis and bag are intact—or in the ciliary sulcus. In the United States, the only FDA-approved option is the CustomFlex ArtificialIris (VEO Ophthalmics), which can be placed in the capsular bag or the ciliary sulcus.

CONCLUSION

Visual outcomes can be affected by iris prolapse. Knowing the key risk factors and prevention techniques and employing the appropriate management decisions can help to ensure a satisfactory outcome.