Most cataract surgeons will encounter a dropped nucleus at some point in their careers. This is especially true for those who take on nonroutine cases. Proper training and clear thinking can help to provide the highest level of care to patients who experience this dreaded complication.

KNOW WHO IS AT HIGH RISK

The preoperative cataract evaluation is a critical step in planning for potential complications during surgery. What should you look for?

Any risk factor for generalized complications during cataract surgery is a risk factor for a dropped nucleus. This can include poor visualization because of a small pupil or intraoperative floppy iris syndrome and a mature or dense cataract. Other factors such as zonulopathy, prior trauma, and a history of ocular surgery (eg, vitrectomy) also raise concern about a possible complication.

Which risk factors are most dangerous specifically for a dropped nucleus? An article published in 2020 reviewed 1.7 million European cataract surgeries and created a list of the leading causes of a dropped nucleus.1 The multivariate analysis found the following statistically significant risk factors, listed in order of significance:

- White cataract;

- Prior vitrectomy;

- Poor preoperative visual acuity;

- Small pupil;

- Pseudoexfoliation; and

- Diabetic retinopathy.

I was surprised to see white cataract at the top of the list, but it makes sense. White cataracts can be pressurized, soft or very dense; fibrotic; iatrogenic (scan the QR code now to watch a related video); or posttraumatic with zonulopathy. In short, white cataracts are unpredictable in nature and harbingers of bad things to come.

YOUR SHIP IS SINKING

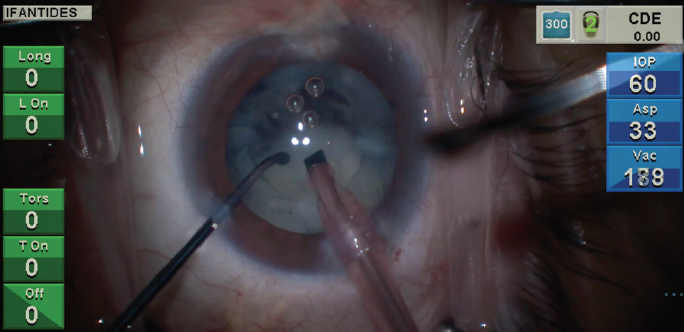

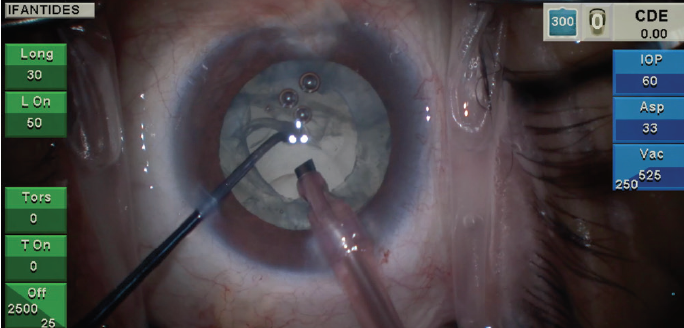

Imagine the lens begins to sink during surgery (Figures 1 and 2). This is not an ideal time to make a game plan. Prepare in advance for the worst by determining the equipment and products you will need to get the job done (see Things You Should Have on Hand,).

Things You Should Have on Hand

- Sub-Tenon block (lidocaine and/or bupivacaine)

- 10-0 nylon sutures

- Anterior vitrectomy handpieces

- Triamcinolone acetonide

Figure 1. A lens sinks rapidly after attempted horizontal chop in an eye with a cataract that formed recently after pars plana vitrectomy.

Figure 2. Loss of the red reflex and a subincisional violation of the posterior capsule are visible in the same patient seen in Figure 1 with recent cataract formation following pars plana vitrectomy.

Much of my strategy depends on the resources available to me. I have worked on five different continents in low-resource settings. My approach to a dropped lens depends on access to retinal care and the burden placed on the patient. If there is no realistic option for retinal care, I may be more aggressive about trying to retrieve a fallen lens. This situation has happened to me only once abroad, but realizing that you have no retina backup is stressful. I advise giving this matter serious consideration before deciding to do surgical work abroad without adequate training. This article, however, focuses on high-resource environments such as the United States, Canada, and Europe. In this setting, I have five main goals when a dropped nucleus occurs.

Goal No. 1: Ensure adequate pain control. The administration of a sub-Tenon block is helpful because surgery will take longer than expected and you want your patient to be comfortable. Prioritize anything you can do to reduce the patient’s pain and fidgeting. I favor a 50/50 mixture of lidocaine 2% without epinephrine and bupivacaine 0.75% injected using a Greenbaum cannula placed through a conjunctiva-Tenon cutdown. This provides quick, short-acting anesthesia, and it can keep pain at bay for hours.

Goal No. 2: Remove vitreous from the anterior segment. A thorough anterior vitrectomy is crucial if the presence of vitreous in the anterior segment is suspected. Otherwise, cystoid macular edema, infection, and retinal tears or detachment may occur. Vitreous strands can also compromise the placement of an IOL. I suture the main wound and create a separate paracentesis to improve fluidics and chamber stability. Even if the suture must be cut to allow the placement of an IOL and the main wound sutured again, these steps are worth the time.

Triesence (triamcinolone acetonide, Alcon)—either dilute or small undiluted quantities—is used to stain vitreous if present in the anterior segment. Kenalog (triamcinolone acetonide, Bristol-Myers Squibb) may be administered for the same indication, but it is considered an off-label use.

If you use the Centurion Vision System (Alcon), I recommend making a separate procedure setting that is dedicated to anterior vitrectomy (procedure 8, for instance). By creating an entirely separate procedure setting, you can use the footpedal to switch back and forth between Cut I/A and I/A Cut without the help of your scrub tech (special thanks to Greg Glassman from Alcon for teaching me this).

Goal No. 3: Place a lens. Implanting an IOL optimizes the patient’s ability to see even if a cataractous lens is in the vitreous. Of course, a posterior chamber IOL requires adequate anterior capsular support. The options are to place a three-piece IOL in the sulcus or with optic capture or to implant a three-piece or one-piece acrylic IOL in the bag using reverse optic capture. For any optic capture procedure, an intact capsulotomy that is smaller than the optic is necessary. If capsular support is inadequate, I do one of two things: Either I place an anterior chamber IOL, or I leave the patient aphakic and consider placing a secondary IOL at a later time. This decision depends on the age of the patient; the risks of glaucoma, uveitis, and corneal endothelial disease; and the patient's overall visual prognosis.

Goal No. 4: Allow a retina colleague to address the dropped lens. Fishing for a dropped or dropping lens can lead to pain, cystoid macular edema, and retinal tears or detachment. Personal ego must be put aside, and the retrieval of the lens must be left to a retina colleague. Even if you get most of the cataract out, residual nuclear chips, epinucleus, or cortex may cause persistent inflammation, pain, and hardship for the patient.

Goal No. 5: Know when to watch and when to refer. Some cataract surgeons prefer to observe patients to see if retained nuclear fragments resolve on their own. Many articles have been published on the optimal timeline for vitrectomy in an eye with a dropped nucleus or retained nuclear fragments, and the argument for early referral and surgery has been well documented. A particularly useful systematic review and meta-analysis focused on the timing of vitrectomy for retained lens fragments. Vanner et al concluded that significantly better outcomes (visual acuity, retinal detachment, increased IOP, intraocular infection/inflammation) are achieved with earlier vitrectomy.2 For these reasons, I prefer early referral and management by the retina team.

POSTOPERATIVE DISCUSSION WITH THE PATIENT

This is a difficult conversation to have, but it is much easier if this complication was addressed with patients during informed consent. Because I perform fewer routine surgeries these days, my preoperative conversations are robust. I cover general risks but also highlight the specific issues for which a patient may be at increased risk.

My conversation always includes the following statement: “If I don’t feel like I can get all of the cataract out safely, or if I can’t implant the lens safely, there could be a need for more surgery later. I will do whatever I think is safest for your eye.”

Even with routine surgery, you are much better off not breezing through the informed consent. If you discuss potential complications in depth with patients before surgery, you can lean on that discussion after surgery when you talk to them about an intraoperative complication.

BE YOUR PATIENT’S ADVOCATE

Studies show that deserting patients, devaluing or failing to understand their and/or their family’s views, and communicating information poorly are major components of malpractice claims.3 When complications arise, showing the patient that you care about the outcome takes time, energy, and focus. It can derail an efficient clinic or OR schedule. It is, however, the easiest way to avoid erosion of the doctor-patient relationship. More importantly, it is the right thing to do, and it is something we would expect from our own doctors if a complication happened during cataract surgery on our eyes.

1. Lundström M, Dickman M, Henry Y, et al. Risk factors for dropped nucleus in cataract surgery as reflected by the European Registry of Quality Outcomes for Cataract and Refractive Surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46(2):287-292.

2. Vanner EA, Stewart MW. Vitrectomy timing for retained lens fragments after surgery for age-related cataracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(3):345-357.e3.

3. Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice. Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(12):1365-1370.