INTRODUCTION

In February, more than 200 physicians and industry leaders gathered in Aspen, Colorado, for the American-European Congress of Ophthalmic Surgery (AECOS) Winter Symposium and discussed trends and innovations in ophthalmology. The premium IOL channel always makes the list of hot topics. A variety of premium presbyopia- and astigmatism-correcting IOLs is available in the United States, and many ophthalmologists recognize that these IOLs can offer advantages that standard IOLs cannot, including greater chance for spectacle independence, better visual acuity, and astigmatism correction when using toric IOLs.

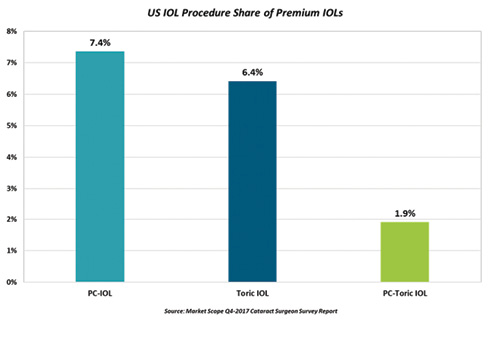

It remains puzzling why the market has been stagnant (Figures 1 and 2), rising from 6.8% market share in 2009 to 7.4% market share in 2017, as reported by Market Scope.1,2 This panel discussion examines why the premium IOL channel has remained relatively flat during the past 10 years and what it will take to increase the market penetration.

—Stephen G. Slade, MD, FACS; and Steven J. Dell, MD

Figure 1. US market share in the premium IOL channel in 2017. (Abbreviation: PC-IOL, presbyopia-correcting IOL)

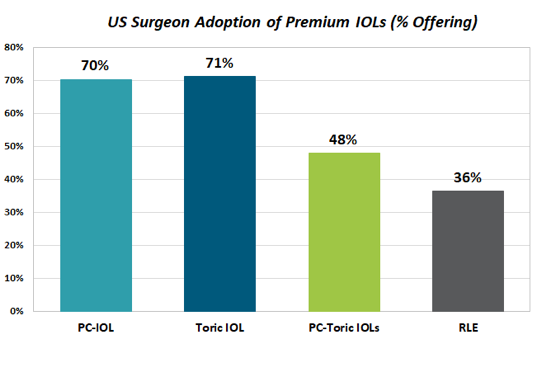

Figure 2. US surgeon adoption of premium IOLs in 2017. (Abbreviation: PC-IOL, presbyopia-correcting IOL)

SNAPSHOT OF THE REFRACTIVE IOL MARKETPLACE: 2009 TO 2017

J. Andy Corley: In 2009, after 5 years of existence of refractive presbyopia-correcting IOL technologies, cataract surgeons only achieved about 6.8% market penetration, when we all believed by that point that it would be closer to 20% to 25%. We postulated that either the lenses or the surgeons were not good enough, but neither was true. What was more true was that asking a patient for money, promising an outcome, and then having to deliver on that promise was very discomforting to a large segment of the surgeon population.

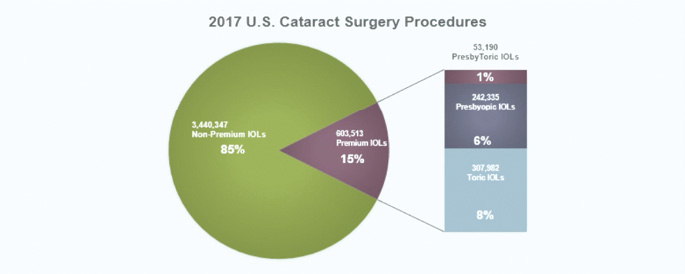

Fast forward to 2017, and more than 600,000 premium cataract procedures were performed in the United States (Figure 3). The overall market has grown, but the presbyopia-correcting IOL market has remained flat at only 7.4% market share.

Figure 3. US premium IOL channel market share in 2017.

Ten years ago, only 25% of surgeons offered premium IOLs to their patients;1 now 80% do.2 However, 75% of that group implant fewer than 40 premium IOLs per year.2 In other words, the majority of practitioners are premium-channel surgeons, but only a minority fully embrace the commitment required of premium lens offerings. In reality, the number of dedicated premium-channel surgeons has not increased in 10 years.

So where are we now? We have better diagnostics, formulas, and IOLs, and we also have femtosecond lasers and aberrometry technology. We also have the toric IOL category, which has helped to double the penetration of the premium IOL channel in the overall cataract market.

The questions for today’s panel are these: Will the premium channel double again in the next 10 years? If so, what are some of the opportunities? Is monovision an opportunity? Have we fully examined the toric opportunity? (Only 8% of patients receive toric IOLs, yet 70% of patients have enough astigmatism to qualify for a toric procedure.2) In 2025, we will hopefully have new presbyopia-correcting toric IOLs, new generations of femtosecond lasers, exchangeable and adjustable IOLs, and maybe even office-based surgery. How will this affect the premium IOL market?

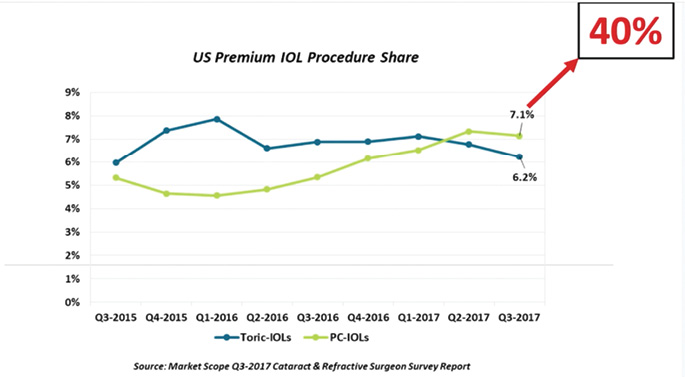

THE FUTURE OF THE PREMIUM IOL

Vance Thompson, MD, FACS: From my viewpoint, the future of the premium IOL is bright. The idea of premium cataract surgery and what is happening right now in this space has had a major impact on my practice. Today, presbyopia-correcting implants account for 40% of the lenses I implant, and that doesn’t include toric IOLs (Figure 4). The impact of these lens technologies has been astounding.

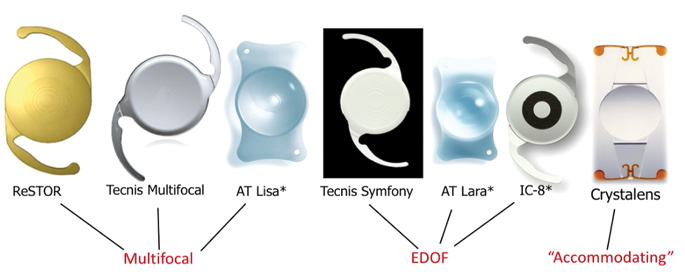

The list of available IOL options now includes multifocal, extended depth of focus, accommodating, and light adjustable (Figure 5). But we also know that our refractive precision needs to improve. Posterior corneal astigmatism, postoperative corneal healing, and effective lens position all can reduce the level of refractive accuracy.

Figure 4. Current premium IOL procedure market share in the United States (blue and green lines on the plot chart) compared with premium IOL market share at Vance Thompson Vision (red arrow).

Figure 5. A partial list of premium IOL implant options. (Abbreviation: EDOF, extended depth of focus)

*The AT LISA (Carl Zeiss Meditec), AT LARA (Carl Zeiss Meditec), and IC-8 (AcuFocus) IOLs are not approved for use in the United States.

The most basic and important elements needed to be a premium cataract surgeon are an implant and an enhancement plan. It amazes me how many doctors don’t have a plan for the refractive enhancement. I think the hope to optimize patient satisfaction is one of the main reasons why many surgeons have tried premium IOLs, and the main reason why many surgeons have abandoned them is patient dissatisfaction. This is because the surgeon didn’t know how to enhance the postoperative UCVA. Right now, enhancing premium cataract surgery involves corneal refractive surgery, and there are many surgeons who don’t want to learn the necessary skills in corneal refractive surgery, and there are many patients who don’t want to have PRK or LASIK after premium cataract surgery.

If I was a company trying to determine how to move the needle and break through this barrier of how to improve premium cataract surgery, I would be looking closely at this issue and educating everyone on what we have learned with LASIK patient satisfaction: UCVA drives patient satisfaction. If you look at a 2016 study by Steven C. Schallhorn, MD, 19% of patients with 20/25 UCVA after LASIK reported that they were unsatisfied. We need to be targeting 20/20 or better in premium cataract surgery. Surgeons who are trying to enter the premium market rely on preoperative testing technologies to determine if someone is not a good candidate for a corneal enhancement postoperatively, or maybe they are a really good candidate with low corneal multifocality. They are intimidated by determining who is a candidate for a laser fine-tune of their cornea, and they are intimidated by the prospect of performing corneal refractive surgery after premium IOL surgery. And, besides that, they are busy. When you are educating the patient on which IOL to choose, refractive surgeons approach this differently than cataract surgeons. We need to teach cataract surgeons who are going into refractive cataract surgery how to educate patients on advanced implant technologies.

If we are going to break this barrier and see premium implants grow in our world, we need to educate surgeons who desire to add or grow this area of their practice on what it takes to build a modern day refractive cataract surgery practice. (To find out Dr. Thompson’s top five tips for building a modern practice, see First Steps to Beginning With Premium IOL Surgery.) Ways to adjust an implant’s power postoperatively, inside the eye, will be available in the future. We will soon have the ability to take an optic (that is inside the patient’s eye!) and actually change the polymer in a way that is going to allow a patient to choose exactly what sort of vision he or she wants. This is exciting because for the first time we will be able to simulate it for them postoperatively. Currently, patients with cataract evaluations have blurry vision, and we can’t show them different types of vision, such as monovision, because they are blurry. When we can put in a light adjustable lens, we can tell patients not to worry about where exactly they want their vision focused after surgery; rather, we can show them the various options when they have clear vision at about 3 weeks postoperatively. I think this is going to stimulate this premium lens market tremendously. I think patients would rather have their implant adjusted than their cornea adjusted. The ease of adjusting the refractive state of the eye by adjusting implant power inside the eye is going to be huge.

DEFINING ADOPTION

Stephen G. Slade, MD, FACS: If we define premium IOLs as presbyopia-correcting and astigmatism-correcting toric IOLs, 60% of the IOLs we implant at our practice are presbyopia-correcting and 20% are toric. In total, therefore, we are implanting a premium IOL in 80% of our patients. How does this measure up to others?

Steven J. Dell, MD: Ten years ago, our practice was implanting a premium IOL in 60% to 70% of patients, and it is still 60% to 70% today.

Slade: Why do physicians accept toric IOLs, as there has been growth in that market, but the presbyopia-correcting lens market is about the same? Let’s solve that problem.

John F. Doane, MD: I think there are two reasons that market hasn’t grown. The first, for our practice, is that a certain percentage of physicians simply don’t want to ask patients for money. Either it is a moral or ethical reason, but they don’t feel comfortable talking about the cost of the premium IOL. The second is that we have had surgeons who have gone down the multifocal pathway but have had issues with patient complaints. What I have found over the years is that if the surgeon has a bad experience with one lens, he or she tends to discontinue using all premium lenses. I think the biggest barriers to better adoption of premium IOLs include a lack of availability of technology to enhance vision postoperatively, not wanting to talk about the cost with patients, and previous negative experiences with a lens.

Slade: I agree, and I would define negative experience as explant rate.

Kendall E. Donaldson, MD, MS: I think there are two types of cataract surgeons: traditional cataract surgeons and refractive cataract surgeons. In order to be a refractive cataract surgeon, you must have the infrastructure in your practice to create a successful premium practice.

Practices need to be designed toward the propagation of the premium channel, and you need to have the right staff in place. Premium cataract surgeons have technology to help us provide the best refractive outcomes possible, but the average cataract surgeon may not be in that situation.

Slade: Are you successful with premium IOLs in your university setting at Bascom Palmer?

Donaldson: It is a challenge, and it is time-consuming. We are always fighting to put the right staff in place. But if I had a concierge practice, which is hard to do in an academic center, it could be easier. I would have the right staff to properly educate patients and guide them through the pre- and postoperative experiences.

This time-consuming process could then be removed from the physician and allocated to someone else. You need to have the infrastructure, the time, and the ability to do all of these things successfully in order to cater to premium IOL patients.

Corley: Can we be more granular on the presbyopia component of the channel? The lenses are better today, and doctors are better trained than they were at the outset of premium IOL surgery. We started the premium channel with immersion A-scans, and now we have so many new devices. It is curious to me why the presbyopia-correcting IOL category has remained flat in light of this. John, what are your thoughts?

Doane: You are preaching to the choir with this group of surgeons. Ophthalmologists send patients down the road to the optical shop; they aren’t doing the transaction, and they aren’t asking for money. I have my discussion with the patient, and staff educators talk money.

Slade: That is a good point. Even though we have a high conversion rate in our practice, I don’t talk money to the patients. Everybody tells me I should.

Dell: Who has a partner who does high-volume cataract surgery but doesn’t want any part in premium IOLs? When you are trying to coexist within your refractive cataract surgery practice, as Kendall mentioned, it is an infrastructure challenge because your waiting room is a zoo. They are running a large volume of people through the office, and when you try to establish a concierge experience where the patient is offered refreshments and waits 5 minutes to see the doctor, that is a difficult thing to do in the environment I described.

Guy M. Kezirian, MD: Andy and I worked on this years ago, and I think we have diagnosed the problem pretty well. If a lens surgeon is not a refractive lens surgeon in 2018, there is only one reason: It is because he or she doesn’t want to be. When this IOL category rolled out, we targeted cataract surgeons, thinking they would be enthusiastic refractive surgeons, and the reality is that they are not.

The culture change it is going to take to grow this market sector is probably not possible with existing surgeons. We need to focus on the younger surgeons who accept this as being normal and who will embrace the concept of being a refractive cataract surgeon.

Kenneth J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS: I think that now, in New York, there are many surgeons who do not offer advanced-technology lenses, and the reason why is simple: They haven’t learned techniques necessary to perform this type of surgery, and they don’t want to refer patients out for it. The surgeon will say to the patient: “You need cataract surgery. Please see my surgical coordinator,” and that is the end of the discussion. The discussion should be: “Advanced techniques and lenses are available, and you may benefit from one. I don’t perform this surgery, but I can refer you to someone who can.”

There is an economic disincentive to refer patients out if you don’t perform a procedure, and I think this is wrong-minded. Informed consent consists of providing the patient with all risks, benefits, and options available. If there is something out there that could benefit a patient, and you don’t tell the patient about it, I think there is a disconnect with good clinical practice.

What is the solution? Maybe part of the solution is for those doctors to know they must disclose the other choices. I think it is a huge problem, and I often see patients postoperatively who are referred to me because they are unhappy with their UCVA and have now heard they could have had a different type of surgery to correct their vision.

William F. Wiley, MD: One thing I see missing is buy-in from optometry. I think we need better education in that community. I think optometrists are often the gatekeepers to these technologies. If the optometrist doesn’t recommend a premium technology, it is harder for a surgeon to recommend it.

Slade: It is a wonderful strategy to have an optometrist who you can partner with in your office. That OD can talk to the patient and introduce the idea of a premium IOL before the patient sees you.

In terms of IOL technology, it is difficult to make a recommendation to someone for a lens that can’t be changed in the future. Many of my patients aged 50 or older will ask me, “If something better comes along, can I have that?” And in truth, I have to tell them no.

One small piece of the puzzle is that refractive cataract surgeons are the people who are doing many of these procedures. By definition, those surgeons have many postrefractive surgery (LASIK, RK, and PRK) patients in their practice. The plea to the industry is to give us lenses that are compatible with postrefractive patients. In my experience, the Crystalens (Bausch + Lomb) is as compatible as a monofocal, and it is one of the reasons why we have had so much success with it.

Dell: I think the financial component of it is a big part of the story. Let’s imagine that cataract surgery was not a covered service in the United States. Someone came to you for a monofocal, and he or she had to pay $5,000. Think about the FDA grid on every monofocal IOL that you have ever seen and the percentage of patients who would not have the same IOL again; there is always 2% to 3% of patients who say, “I received this lens for free because I was in a clinical trial, but I wouldn’t choose this lens again.” If monofocal IOLs were $5,000, I think the number of people who are dissatisfied with them would be significant. There would be 3% to 4% of patients who would say, “I don’t like the way I see with this lens.

Slade: Vance, you have had experience with the Light Adjustable Lens (»RxLAL, RxSight), but that was in a clinical trial setting. Patients don’t experience the benefit right away, so how do you sell that technology to patients?

Thompson: One of the benefits of monovision is that, if someone is unhappy in certain situations, such as nighttime driving, he or she can put on a pair of glasses and clear it up beautifully.

But we also know that, in the dominant eye, or at least the distance eye, achieving as close to plano as possible is important for optimal monovision success. I like to call this precision monovision. This idea of not only monovision, but precision monovision, is going to be more interesting to all cataract surgeons, even to those of us who do a high volume of multifocal and extended depth of focus procedures.

Slade: But what is going to be your discussion? Talk to me like a patient.

Thompson: I think it motivates patients when I tell them, “We do these preoperative measurements to figure out the best implant power for you, but this implant is not specifically made for your eye. We won’t know the exact implant you need until we see you postoperatively due to a variety of factors, such as the final resting position of your implant or any astigmatism that may have increased or decreased with healing. What is beautiful about this advanced premium implant is that we still do all of those same measurements that we do with every implant, but then we put it into your eye, and when it settles into position at 3 weeks postoperatively, we can get better measurements. We can then use a laser to truly, for the first time in the history of cataract surgery, adjust its power to your eye and your desires. It will be an implant made specifically for you and customized inside your eye. It is like a dream come true.”

Donaldson: I think we have to remember that the surgeons participating in this discussion are sometimes more willing to adopt new technologies than others. I know Vance has a wonderful practice, and most of us here have great practices that are designed around refractive technology. But I have a colleague who won’t put any premium lenses in patients, and she says, “You have all of these premium lens options, but clearly you haven’t gotten it right yet.”

Bennett Walton, MD, MBA: I think we should consider not calling it a premium lens when discussing options with patients. First of all, what we have isn’t really good enough to label it with such a value-add word. We are still not fully restoring vision to a young, healthy state. I don’t believe what we have is good enough to call it premium, but it is certainly good enough to change a lifestyle with, and it makes a difference to patients who select advanced lenses. I think the verbiage is crucial here; premium can be a surrogate for fancy or bells and whistles, leading to a negative connotation in some markets.

The Premium IOL Channel: Pitfalls and Prospects

Thompson: One thing that is so wonderful about a traditional cataract surgery with a monofocal implant is that after surgery the patient leaves, they receive glasses 1 month postoperatively, and you oftentimes never hear from them again because they are satisfied. One of the things we do with every single advanced implant we perform is to contact the patient at 1 month postoperative to gauge how they are responding to the surgery. I receive a report every week that includes a list of patients who are 1 month out, and we track their satisfaction. If I see anyone who is not satisfied, I call them personally.

At 3 months, we examine each patient in person because we want to make sure he or she is satisfied, and if he or she is not, we will perform a laser fine-tune. It is important to have patients understand what healing blur is and to realize that most cataract surgery procedures need a fine-tune postoperatively; with traditional cataract surgery, the fine-tune is glasses at 1 month and with advanced cataract surgery the fine-tune is a laser touchup of their cornea at 3 months. With light adjustability, the fine-tune will be a laser adjustment of their implant at 3 weeks postoperative. I tell them to count on requiring a fine-tune, and if they don’t need it because they are seeing crystal clear, then we love that too.

Slade: Great idea. Andy, you had the first comment in this discussion, so why don’t you also have the last.

Corley: I do believe future IOL technology will expand the premium channel, and I do believe the premium channel will double again in the next 10 years. The motivations and the incentives for all of us are high, and it provides ancillary benefits like the incentive to fund other technologies.

We spent time today on how we talk to patients, and I think that is something industry can play a bigger role in, trying to be helpful to our physician community (see Is Consumer Advertising the Answer?).

We hear people say: “People love to buy and hate to be sold.” If we can continue to improve the outcomes patients achieve after cataract surgery with a premium lens and find the proper ways to educate patients with the right information, I believe patients will continue to buy into premium offerings.

Slade: Thank you, everyone. That was one of the best discussions we have had in a while.

1. 2009 Global IOL Report. Market Scope. Published 2009. Data on file.

2. 2017 Annual US Cataract Surgeon Survey Report. Market Scope. https://

market-scope.com/products-page/cataract-reports/2017-annual-us-cataractsurgeon-survey-report. Published May 2017. Accessed April 4, 2018.

3. Schallhorn S. Lessons learned in refractive surgery. Paper presented at: the

AECOS 2016 Winter Symposium; Aspen, Colorado; February 28-March 2, 2016.