Patients with keratoconus can experience disease progression at any age, but it tends to be more rapidly aggressive in younger patients than in those who are middle-aged or older. One of the greatest challenges occurs when children or adolescents present with keratoconus in one or both eyes. The patients and their families will want to know how urgent corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) is. Can the procedure wait a few months for a school holiday or summer vacation, or should it be performed in the next few weeks?

AT A GLANCE

• Keratoconus can progress rapidly during childhood and adolescence.

• It is important to monitor these patients closely.

• Once keratoconus has been diagnosed, a discussion of the risks and benefits can help the patient and his or her family understand how corneal collagen crosslinking can have a significant impact on preventing the condition from worsening.

CASE EXAMPLE

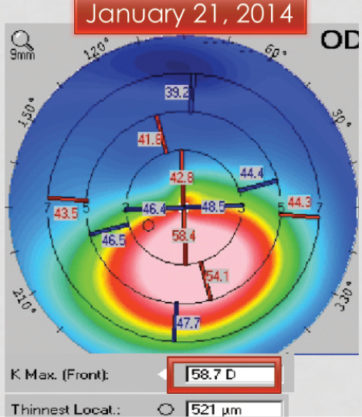

A 10-year-old boy with keratoconus presented for a consultation in January 2014 (Figure 1). The maximum corneal curvature (Kmax) in the right eye was 58.70 D, and the corneal thickness was 521 µm. The family asked if it would be OK to schedule CXL for spring break and, after a lengthy discussion, decided to wait until April for the procedure.

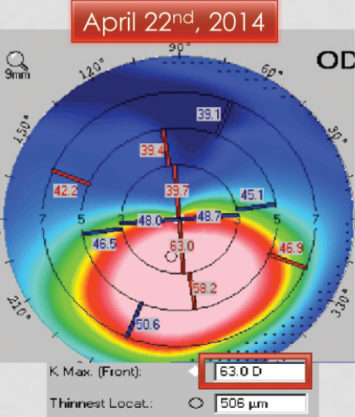

Unfortunately, when the patient returned in 3 months, the keratoconus had progressed significantly. The Kmax had steepened to 63.00 D, and the cornea had thinned to 506 µm (Figure 2). The patient had also lost 1 line of BCVA. Thankfully, he underwent CXL in April 2014, and the procedure stabilized both eyes.

Figure 1. Initial presentation. Significant inferior corneal steepening is consistent with keratoconus.

Figure 2. Three months later, the patient returned for CXL. The keratoconus has progressed significantly, with an increase in Kmax to 63.00 D and thinning of the cornea.

LESSONS LEARNED

As this case demonstrates, it is important for clinicians to be aware that keratoconus can progress rapidly during childhood and adolescence. Although the frequency of follow-up visits with repeat corneal mapping to identify disease progression for adults can range from every 6 to 12 months, children and adolescents can require shorter intervals. On examination, the two tests that are most helpful to determining the stability or progression of keratoconus are refraction with BSCVA and corneal imaging (topography/tomography).

Once keratoconus has been diagnosed, a discussion of the risks and benefits can help the patient and his or her family understand how CXL can have a significant impact on preventing the condition from worsening. FDA-approved in the spring of 2016, CXL halts the progression of keratoconus and improves corneal shape. Many patients who have undergone the procedure can experience some improvement in quality of vision and BCVA.

CONCLUSION

Although CXL is not considered an emergency procedure, it is important to monitor young patients and adolescents with keratoconus closely. Disease progression can occur rapidly in this population. CXL has a long history of helping patients with keratoconus, and the recent FDA approval solidifies clinicians’ understanding of the procedure’s importance in patients with progressive disease.