Since pledging to uphold the Hippocratic Oath that I recited upon entering medical school, I have tried to adopt traits that I believe are meaningful and add value to my life. They include kindness, compassion, a strong work ethic, sharing knowledge, striving for excellence, challenging the accepted, and integrity. I am so fortunate to have learned many of life’s most important lessons from a handful of mentors in this respected profession.

KINDNESS

There is no greater gift than kindness, and for me, there was no greater mentor than my father. Morris Osher, MD, was a gentle and dedicated ophthalmologist, devoted both to his patients and to his family. When I was a child, my dad would take me to the hospital to make rounds on the weekend, and I observed his genuine kindness and concern for each patient. Moreover, he was always thoughtful and respectful. Like Spencer Thornton, MD, my father had grace.

COMPASSION

After my second year of medical school, I won an award that would allow me to spend a year with virtually any physician who agreed to serve as my preceptor. How lucky I was that J. Lawton Smith, MD, at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute was willing to gamble on me. What I remember most about Dr. Smith is that he was a remarkable clinician. His sincere concern for each patient was legendary. He taught me that, although every patient cannot be cured, every patient can be comforted. The year with Dr. Smith forever changed my life.

STRONG WORK ETHIC

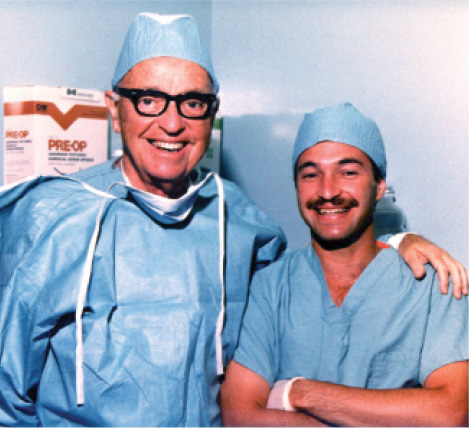

My father’s work ethic influenced all of the Osher children. He never complained about working long days, nights, and weekends. I have never been reluctant to work hard and follow in my father’s footsteps (Figure). I remember he used to kid me by saying that, on Saturday, I only worked a half-day … 12 straight hours!

SHARING KNOWLEDGE

In lieu of an internship, I was granted a special exemption to spend a year with Norman Schatz, MD, at Wills Eye Hospital. He, too, had trained under Dr. Smith and was a gifted clinician and a brilliant teacher. It was a treat to observe how this charismatic physician willingly shared his incredible knowledge with residents, fellows, and practitioners. Dr. Schatz was such a giving individual, and his commitment to teaching had a strong influence on my career.

STRIVING FOR EXCELLENCE

It was a privilege to spend 6 months with J. Donald M. Gass, MD, a renowned retinologist at Bascom Palmer. He was an exceptional observer and an extraordinary ophthalmologist. He advised me to keep a special drawer for cases that I did not understand so that, one day, I might acquire the knowledge and experience to make a scientific contribution. When I think about excellence, Dr. Gass stands out.

CHALLENGING THE ACCEPTED

Figure. A young Dr. Osher learning surgery and the art of medicine from his father, Morris Osher, MD.

I learned from Dr. Smith that “the truth is not defined by the majority opinion.” I believe that I have always been a truth seeker and a bit of a rebel, yet it was Charles Kelman, MD, whose influence guided me through some rough times.

In 1983, I introduced the concept of combining astigmatic keratotomy with phacoemulsification, which was the first attempt to reduce preexisting astigmatism. I was severely criticized for “mutilating” the cornea, even though the concept of refractive cataract surgery seemed a valid scientific approach. I had also riled up a few colleagues by performing the first hyperopic lensectomy back when removing a clear lens was taboo. Then, in the early 1980s, in my first official presentation at the American Academy of Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, I demonstrated how to implant a posterior chamber lens into a torn capsular bag when the standard of care was a backup anterior chamber lens. For challenging the accepted, I was not invited back for 10 years!

A major battle erupted when Cavitron rejected my recommendation to develop a machine with the first surgeon-controlled parameters of ultrasound, aspiration, vacuum, and even automated bottle height. I found a small company in Italy, Optikon, that helped me to introduce slow-motion phacoemulsification, which resulted in my challenging Dr. Kelman’s phaco contraindications that included the loose lens, the mature lens, the shallow chamber, and the small pupil. I was ridiculed by just about everyone for performing phacoemulsification in these complex situations except for a small group of friends, including Douglas Koch, MD; Samuel Masket, MD; Richard Lindstrom, MD; Alan Crandall, MD; and Dr. Thornton.

Imagine my surprise when Dr. Kelman himself sent me a note of congratulations for expanding the indications for phacoemulsification. He befriended me and tried to prepare me for the criticism and isolation that had marked his own career. I was so fortunate to share a special relationship with Dr. Kelman, and I will never forget visiting him at his home and spending time with his family. When he passed away, I felt an enormous personal loss, and ophthalmology lost a great innovator who did not shy away from challenging the accepted.

INTEGRITY

Perhaps integrity is the single value that my mentors had in common. Intellectual honesty and the way each conducted his life were perhaps the most important lesson that they could pass along. I will always be grateful for the wonderful opportunity I was given to learn from these ophthalmologists, whose words and actions continue to guide me in absentia.

Robert H. Osher, MD

• professor of ophthalmology, University of Cincinnati

• medical director emeritus, Cincinnati Eye Institute, Cincinnati

• editor, Video Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery

• (513) 984-5133, ext. 3679; rhosher@cincinnatieye.com