In this installment of “Residents and Fellows,” Yousuf Khalifa, MD, identifies approaches that we mentors should take when teaching trainees. His insight gives young physicians a peek into some of the processes that we implement when we teach. Appreciation of the concepts in this article will certainly accelerate your learning curve and aid in keeping your mentor’s pulse “within normal limits” during surgery!

—Section Editor Sumit “Sam” Garg, MD

There is a certain exhilaration that comes from teaching a young surgeon to chop a nucleus, to place a capsular tension ring, or to manage intraoperative floppy iris syndrome. The surgical mentor feels a sense of pride when his or her young surgeon’s patient comes back happy and with excellent vision postoperatively.

Some may wonder why one would choose a career dedicated to teaching eye surgery to residents; I believe that the motivation lies in knowing that the surgeons we produce in residency will have careers that will long outlast our own and that the good we do today will be multiplied through them and those they teach and care for in the years to come.

On the other hand, when things do not go well in surgery, many thoughts race through the mentor’s mind, including “I hope the patient recovers well” or “I hope the resident doesn’t lose all confidence” or “I should go into private practice or retire.”

The literature shows that students of more experienced teachers achieve better surgical outcomes.1 Regardless of experience, however, there are ways for all cataract surgery mentors to minimize the frequency of complications—for example, the iatrogenic zonular dialysis, the broken posterior capsule, the dropped nucleus—for their mentees. This article outlines five fundamentals for the cataract surgery educator that I hope will lead to longer and more enjoyable teaching careers.

FOLLOW A STRUCTURED SIMULATION TRAINING CURRICULUM

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in the United States requires ophthalmology residency programs to provide wet lab space for residents to practice surgery.2 It is tempting just to tell the resident to go to the lab and practice, but there are seven main requirements for effective skill acquisition in the wet lab, as follows:

1. Easy access to the wet lab space (card-swipe access 24 hours a day). Restricting the hours a wet lab is available or making it accessible only by key discourages residents from actually going to the wet lab. Try to remove all obstacles and make visiting the wet lab effortless.

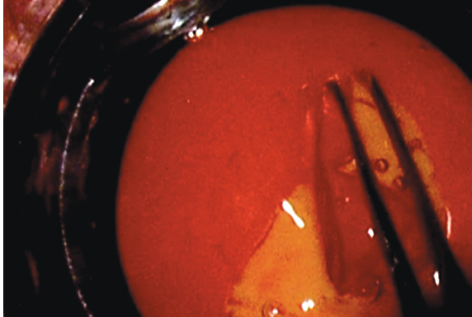

2. A simulation model that mimics the surgical step (tactile and visual). Picking a simulation model can be tricky and expensive. Porcine eyes have a finite life in the wet lab, and the anatomy of the eye can make the resident develop poor technique. The Eyesi Surgical simulator (VRmagic Holding) continues to improve, but the price is prohibitive for many programs.3 Additionally, most programs have only one Eyesi system, which makes it difficult for residents to schedule time to practice without conflict. I prefer the Kitaro DryLab and WetLab system (Frontier Vision); this model is fairly inexpensive, and I find great fidelity for capsulorhexis and phaco training (Figure).4

Figure. Simulation of capsulorhexis creation with the Kitaro DryLab and WetLab system.

3. Instruments that are in working order. Nothing is more frustrating for a resident or attending who is there helping the resident than to waste 30 minutes rummaging around for forceps that are not bent or for a blade that is sharp.

4. Good ergonomics. Tables and chairs with adjustable height and footpedals that rest underneath the table make an environment that is conducive to long hours of practice. Without these features, residents will experience neck and back pain, they will worry about how difficult it is to get comfortable, and they will develop poor technique.

5. Residents’ understanding of what proper technique looks like. Residents often underestimate the complexity of learning cataract surgery and fail to understand basic concepts such as how to center the eye in the field, where to rest their hands; and how to hold the instruments, judge depth, or set the phaco machine. The list goes on. I developed a 5-week course that divides cataract surgery into five steps, with one step covered per week. Each week begins with a didactic lecture that outlines the basics of the step. Next, there is a live demonstration by an experienced surgeon in the wet lab, and then the residents are asked to record themselves performing the task and submit the recording for grading.

6. Attending supervision. The goal of attending supervision is to ensure that residents understand the mechanics of a surgical step and that they are executing it properly in the wet lab. There are three mechanisms for supervision: (1) a microscope side scope, which can cause neck pain for the attending depending on the setup; (2) a camera with a liquid-crystal display screen, which allows the attending to step back and view the simulation practice comfortably in the wet lab; and (3) a camera with video recording, which allows the resident to practice in the wet lab at any time without the attending and allows the attending to provide feedback while watching the recording from the comfort of his or her office.

7. Feedback that is objective, quantifiable, and timely. Most studies have looked at operative feedback, but I have also found wet lab feedback to be essential. Use a standardized form with a rating scale, and set a minimum grade for passing each step.

REVIEW SURGICAL VIDEOS

Traditionally, residents show their surgical videos to an audience only at morbidity and mortality conferences. At Grady Memorial Hospital, we do a biweekly surgical video review in which residents get to show their challenging cases, their successes, and the occasional complication. They present to two or three surgical faculty members, many coresidents, and several medical students. The residents verbalize the challenges they found in making an incision, performing hydrodissection, grooving, cracking, and chopping, to name a few.

I have found this tool to be effective for engaging residents early in their training and getting them to read and think about surgical techniques. I have also found that the surgeon-in-training benefits tremendously from this experience. I recently started bringing a phaco machine from the wet lab and having one of the first-year residents try to work the footpedal to match what is happening on the video.

PERFORM THOROUGH CHART REVIEWS

It can be difficult to find time to sit down with a resident and review charts prior to surgery, but it is vital. Essentials to review include the following:

1. IOL calculations and IOL model and power selection. Going over biometry measurements, pointing out any inconsistent or worrisome results, discussing target refraction, and making sure that the patient has been educated on the potential postoperative refractive outcome are all essential. Discuss special considerations for postrefractive surgery calculations, and review online calculators such as the one available at www.ascrs.org.

2. The patient’s medical history. It is important to prepare residents for challenges such as intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, positioning for patients with breathing problems or skeletal issues, claustrophobic patients, and those with a psychiatric history, especially for posttraumatic stress disorder.

3. The patient’s ophthalmic history and examination. Important questions abound: Is there asymmetry in the cataracts between the two eyes? Is there a history of trauma? What is the preoperative manifest refraction? Were any corneal issues detected at the slit-lamp examination such as anterior basement membrane dystrophy, keratoconus, or Fuchs dystrophy? Is there a history of previous ocular surgery? Any retinal issues? The list goes on, but engaging the resident in a discussion is essential and a great opportunity to teach.

BUILD RESIDENTs’ CONFIDENCE

Nothing stunts the short-term growth of young surgeons like encountering a complication. They become timid and indecisive, which can lead to more complications in subsequent cases. The untoward effects of complications on the patient and resident can be minimized and/or mitigated with several pre-, intra-, and postoperative interventions.

Preoperatively. Attention to the fundamentals discussed earlier can dramatically improve resident performance and decreases complication rates.

Intraoperatively. I believe the attending surgeon must anticipate trouble, see two or three steps ahead, and be ready to offer words of guidance and, if necessary, to take over. The attending should describe and sensitize the resident to what he or she is seeing and the thought process involved. It is of utmost importance to recommend techniques to overcome suboptimal situations before they become complications and to take over when the trainee is unable to execute the desired technique.

Postoperatively. Video review is extremely important. I like to review the complicated and uncomplicated cases from the day and first point out the positive things the resident did throughout. I then go back to the complication event and dissect the video, making sure to discuss instrument and hand position, fluidics, and other reasons for the mishap.

I always feel responsible when a complication happens, and during the video review, I try to see how I can provide better guidance the next time. I ensure that during the very next case I talk calmly and reassuringly to the resident and try not to let him or her sense any loss of confidence in his or her abilities. At the end of the day, I share a story of one of my own humbling complications, and if I have not had a similar experience, I may share a previous trainee’s complication (anonymously). Nothing soothes the soul of a resident who just had a complication like hearing about someone else’s challenging cases.

CHALLENGE BUT DO NOT OVERWHELM

Residents will sense their surgical skills and comfort level improving, and they will often succumb to a feeling of complacency or contentment. Once I feel that the resident has mastered a step or a technique and that his or her confidence is high, I introduce a variation in a step of the procedure. For instance, I take the resident from divide-and-conquer to stop-and-chop and then to horizontal, vertical, and prechop maneuvers. I have the resident change his or her chopper and experiment with smaller keratome incisions. I change the IOL make and model and introduce toric lenses. I have the resident try a different phaco machine and tinker with the settings. My goal is to fashion a surgeon who is not afraid to try new technologies and techniques and to make him or her adaptable and ready for what the future of cataract surgery holds.

CONCLUSION

Although challenging at times, the role of surgical mentor is an incredibly rewarding position to hold. The ability to guide ophthalmologists in training through phases of their professional and personal development is of immeasurable value. With the mentioned fundamentals in place, all surgical mentors—novice and seasoned—can ensure that they are truly setting the next generation of surgeons up for a future of success.

1. Puri S, Kiely AE, Wang J, et al. Comparing resident cataract surgery outcomes under novice versus experienced attending supervision. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1675-1681.

2. Taylor JB, Binenbaum G, Tapino P, Volpe NJ. Microsurgical lab testing is a reliable method for assessing ophthalmology residents’ surgical skills. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(12):1691-1694.

3. Khalifa YM, Bogorad D, Gibson V, et al. Virtual reality in ophthalmology training. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51(3):259-273.

4. Khalifa YM, Hines MA, Gearinger M. The future of surgical assessment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(8):1145.

Yousuf M. Khalifa, MD

• associate professor of ophthalmology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta

• chief of ophthalmology, Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta

• yousuf.khalifa@emoryhealthcare.org

• financial interest: none acknowledged