The corneal epithelium is a dynamic, self-renewing layer with rapid cellular turnover and a remarkable remodeling capacity. The epithelium can thicken, thin, or redistribute itself to smooth out anterior surface irregularities in response to changes in the underlying stroma—whether from trauma, surgery, or progressive disease. Although helpful for maintaining optical clarity, this compensatory behavior can mask early pathology or mimic stromal abnormalities on standard imaging.1-3

Reinstein et al introduced epithelial thickness mapping (ETM) in 1994.1,4 They used very high frequency digital ultrasound scanning to describe epithelial remodeling of the entire cornea in eyes with keratoconus (KCN). Though revolutionary at the time, very high frequency ultrasound–based ETM presents several challenges:

- It is contact-based and time-consuming;

- It requires staff training and specialized equipment not commonly available in clinical settings;

- It is limited to anterior segment imaging; and

- It lacks integration with other ocular imaging modalities that OCT systems offer.

ETM based on spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) emerged in 2011. It is the most commonly used form of ETM in clinical practice today. Image acquisition is fast, noncontact, and widely available because most eye care clinics have anterior segment OCT systems. The first SD-OCT ETM device was the Optovue RT-100 (Optovue), which was followed by the Optovue Avanti (also known as RTVue XR Avanti or Avanti Widefield OCT), the first OCT system to gain FDA clearance for 9-mm ETM.5 The latest advance in ETM is swept-source OCT technology, which offers faster scanning speeds and deeper imaging of the anterior and posterior segments.6,7 Compared to SD-OCT, however, swept-source OCT is generally more expensive and more complex, reducing its accessibility.

Unlike topography and tomography, which reflect combined epithelial and stromal curvature, OCT-based ETM isolates the epithelial profile and reveals hidden patterns that can influence diagnosis, treatment planning, and surgical outcomes. This article explores the clinical applications of ETM and uses five real-world clinical scenarios to illustrate the approach’s value for the management of corneal irregularities.

KEY ETM FINDINGS IN HEALTHY EYES

In eyes without corneal irregularities, ETM reveals a characteristic pattern of the thinnest epithelium centrally (approximately 51–57 µm on average), with progressively thicker epithelium toward the midperiphery. This typical distribution creates a subtle reverse doughnut pattern, reflecting how the corneal epithelium adapts to the underlying stromal curvature.1,8,9 Most studies have found thicker corneal epithelium inferiorly than superiorly, with similar findings consistently seen in studies of children from different ethnic groups.8-15 Additionally, subtle regional asymmetry in corneal epithelial thickness is common in healthy eyes, creating a slightly oblique axis of asymmetry. This may reflect eyelid dynamics and tear film distribution.16 Minimal interindividual variability in central epithelial thickness has also been found depending on the imaging modality, diurnal fluctuations, and population characteristics.3,8,9,17 When the epithelium is thinnest inferotemporally, it may indicate KCN.

The epithelial profiles of an individual’s two eyes are typically symmetric in both thickness distribution and overall shape, making asymmetry between them a sensitive indicator of early or subclinical corneal abnormalities.1,2 ETM of healthy eyes generally shows smooth, gradual transitions in thickness without focal irregularities or abrupt changes.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF ETM IN EYES WITH IRREGULAR CORNEAL SURFACES

Understanding baseline epithelial patterns can help clinicians differentiate healthy corneas from those with surface irregularities. The following five case examples illustrate how ETM can enhance the detection and interpretation of early or irregular corneal changes and assist with management.

Case No. 1

ETM can help with the early diagnosis of KCN by revealing corneal epithelial thinning that may mask underlying stromal changes.1-3,8,18-20 In this case, both eyes showed signs that were consistent with KCN, including localized thinning of the epithelium.

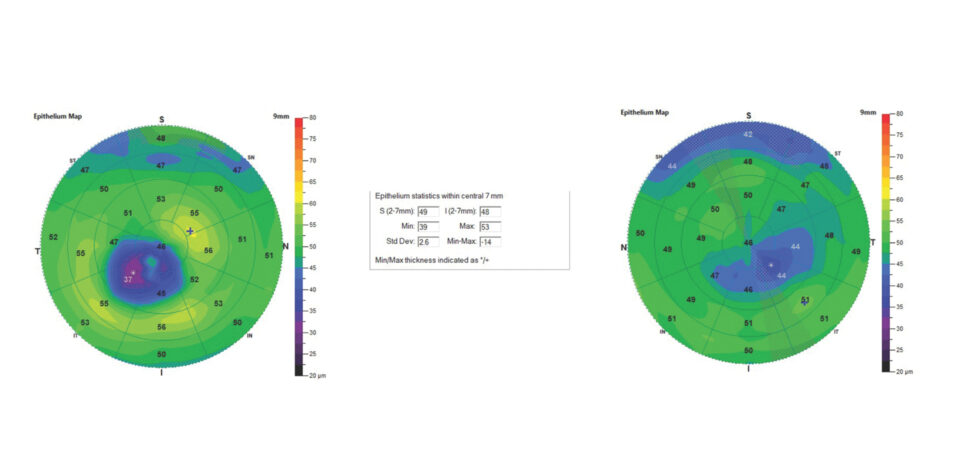

The thinnest epithelial point in the right eye was 31 µm, which is well below the average for a healthy cornea. The thinnest epithelial point in the left eye was 39 µm, which is slightly below normal. The maps for both eyes showed a blue zone corresponding to epithelial thinning overlying an inferotemporal cone (Figure 1).

Figure 1. ETM of the right (A) and left (B) eyes of a patient with KCN. All images included in this article were obtained using the SD-OCT Optovue Avanti.

Case No. 2

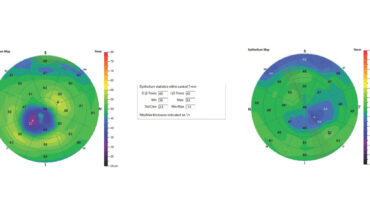

A patient presented for a LASIK consultation. ETM showed mild to moderate KCN in the right eye and mild epithelial changes in the left eye. The minimum epithelial thickness within the central 7 mm of the cornea in the right and left eyes was 27 and 38 µm, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2. ETM of the right (A) and left (B) eyes of a patient with KCN.

The patient was subsequently advised against LASIK, and CXL therapy was recommended.

Case No. 3

Patients with epithelial basement membrane dystrophy (EBMD) often present with central and inferior hypertrophy in the basement membrane.

This patient presented for an evaluation of recurrent erosion syndrome in the right eye, which had been treated with a bandage contact lens. ETM revealed a superior, isolated area of hypertrophy at 63 µm in the right eye and an area of hypertrophy at 64 µm in the left eye (Figure 3). He was diagnosed with EBMD, and therapy with hyaluronate ointment at bedtime was initiated to improve ocular comfort bilaterally and reduce the frequency of erosions in the right eye.

Figure 3. ETM of the right (A) and left (B) eyes of a patient with EBMD.

Case No. 4

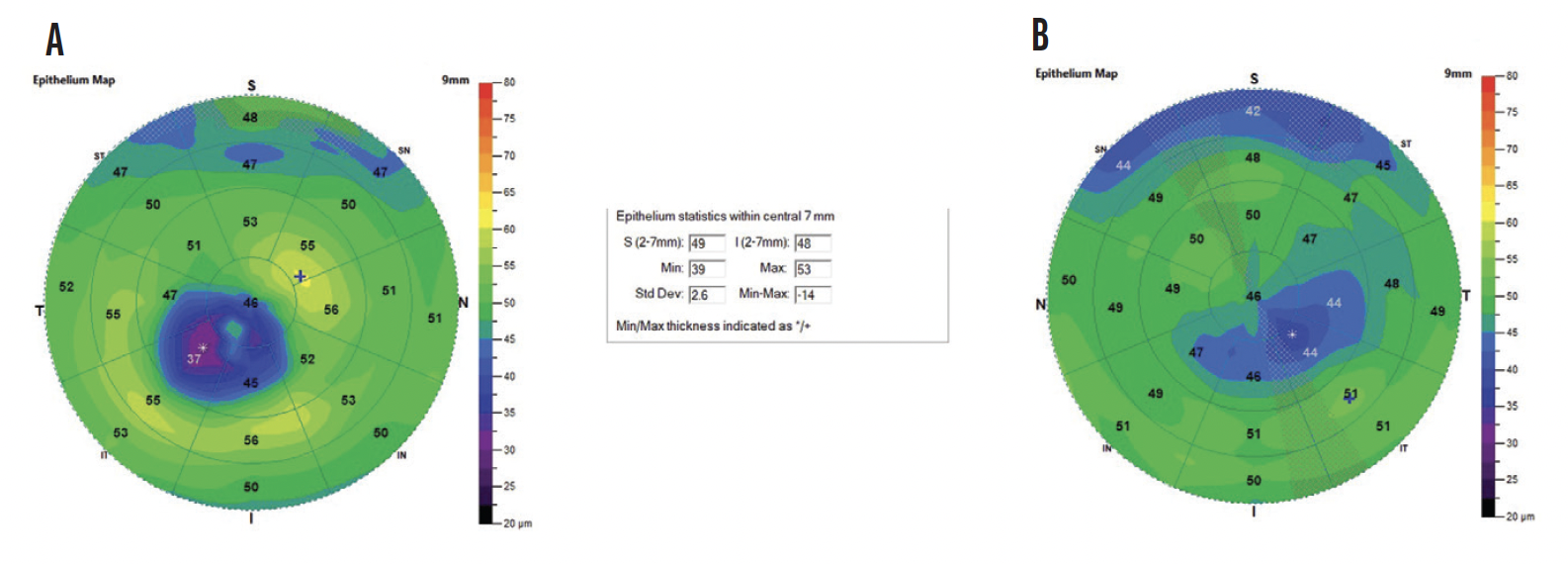

A patient developed myopic regression approximately 3 years after PRK. ETM showed an area of superior hypertrophy ranging from 62 to 70 µm in the right eye and a maximum epithelial thickness of 77 µm within the central 7 mm of the cornea. The left eye had an area of superior and central hypertrophy ranging from 61 to 63 µm and a maximum epithelial thickness of 66 µm within the central 7 mm of the cornea (Figure 4).

Figure 4. ETM of the right (A) and left (B) eyes of a patient who presented with epithelial hypertrophy 3 years after undergoing PRK.

The patient’s myopic refractive error improved after superficial keratectomy alone (with no additional ablation), but the epithelial hypertrophy recurred along with haze. Treatment with a topical steroid and losartan was initiated. A repeat superficial keratectomy with adjunctive mitomycin C may be performed in the future.

Case No. 5

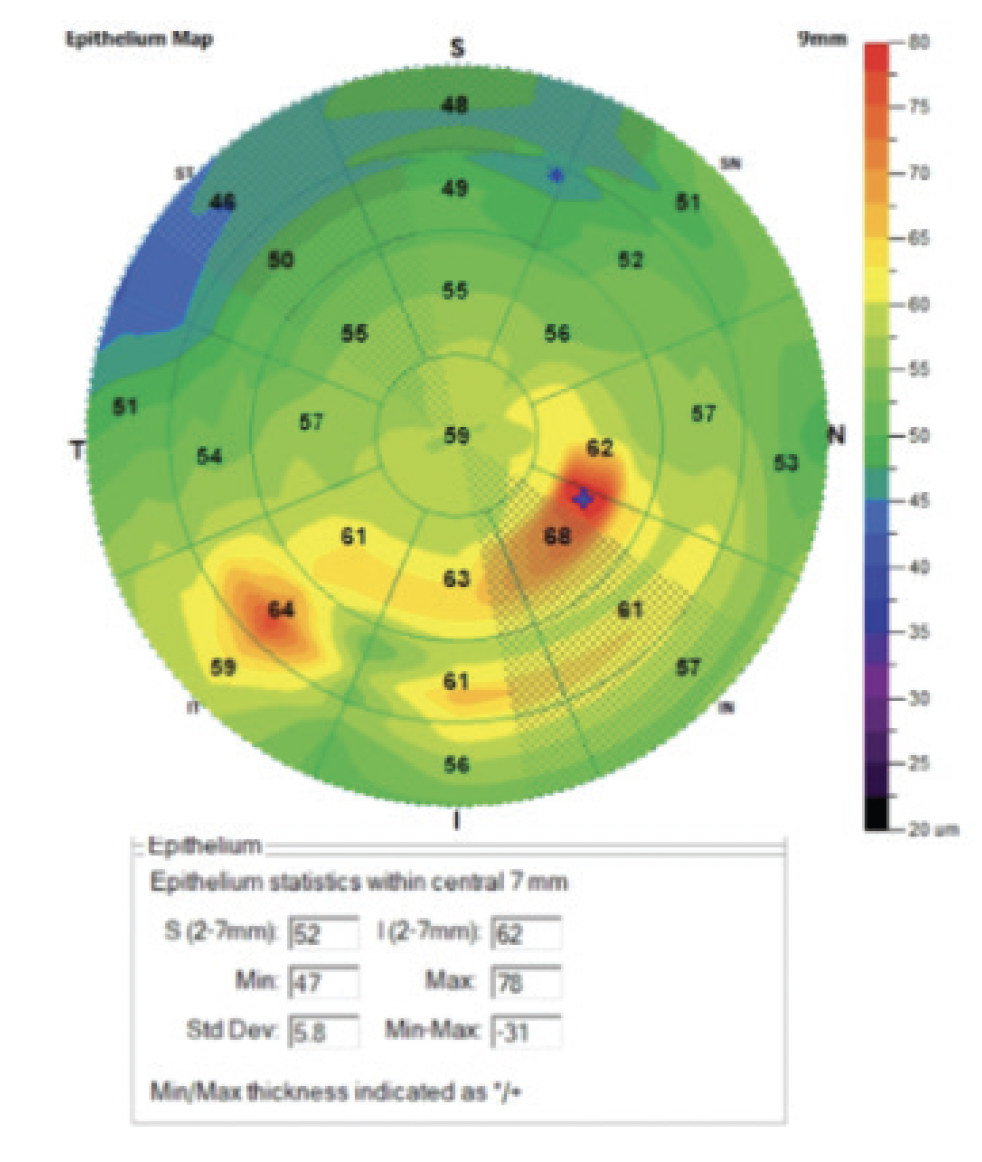

A patient with Salzmann nodular degeneration presented with a complaint of fluctuating, blurry vision in the right eye. ETM revealed multiple areas of thickening ranging from 61 to 68 µm and a maximum epithelial thickness within the central 7 mm of the cornea of 78 µm (Figure 5). Symptoms improved after nodule removal, which created a smoother corneal surface.

Figure 5. ETM of the right eye of a patient with Salzmann nodular degeneration.

CONCLUSION

ETM has become a practical, reliable, and accessible imaging tool that can assist in the early diagnosis and management of corneal surface disorders such as KCN, EBMD, Salzmann nodules, recurrent erosions, and epithelial hypertrophy after PRK. ETM can also help determine patients’ candidacy for refractive surgical procedures such as LASIK and facilitate optimization of the ocular surface before cataract surgery.

1. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M. Corneal epithelial thickness profile in the diagnosis of keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 2009;25(7):604-610.

2. Rocha KM, Perez-Straziota CE, Stulting RD, Randleman JB. SD-OCT analysis of regional epithelial thickness profiles in keratoconus, postoperative corneal ectasia, and normal eyes. J Refract Surg. 2013;29(3):173-179.

3. Kanellopoulos AJ, Asimellis G. Epithelial thickness mapping as a diagnostic tool for keratoconus and post-LASIK ectasia. Eye Vis (Lond). 2014;1:5.

4. Reinstein DZ, Silverman RH, Coleman DJ. High-frequency ultrasound measurement of the thickness of the corneal epithelium. Refract Corneal Surg. 1993;9(5):385-387.

5. El Wardani M, Hashemi K, Aliferis K, Kymionis G. Topographic changes simulating keratoconus in patients with irregular inferior epithelial thickening documented by anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:2103-2110.

6. Shoji T, Kato N, Ishikawa S, et al. In vivo crystalline lens measurements with novel swept-source optical coherent tomography: an investigation on variability of measurement. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2017;1(1):e000058.

7. Asam JS, Polzer M, Tafreshi A, Hirnschall N, Findl O. Anterior segment OCT. In: Bille JF, ed. High Resolution Imaging in Microscopy and Ophthalmology: New Frontiers in Biomedical Optics. Springer; 2019:285-299.

8. Li Y, Tan O, Brass R, Weiss JL, Huang D. Corneal epithelial thickness mapping by Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography in normal and keratoconic eyes. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2425-2433.

9. Haque S, Jones L, Simpson TL. Thickness mapping of the cornea and epithelium using optical coherence tomography. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85(10):E963-E976.

10. Temstet C, Sandali O, Bouheraoua N, et al. Corneal epithelial thickness mapping using Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography for detection of form fruste keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(4):812-820.

11. Reinstein DZ, Gobbe M, Archer TJ, Silverman RH, Coleman DJ. Epithelial, stromal, and total corneal thickness in keratoconus: three-dimensional display with Artemis very-high frequency digital ultrasound. J Refract Surg. 2010;26(4):259-271.

12. Feng Y, Reinstein DZ, Nitter T, et al. Heidelberg Anterion swept-source OCT corneal epithelial thickness mapping: repeatability and agreement with Optovue Avanti. J Refract Surg. 2022;38(6):356-363.

13. Loureiro TO, Rodrigues-Barros S, Lopes D, et al. Corneal epithelial thickness profile in healthy Portuguese children by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:735-743.

14. Beer F, Wartak A, Pircher N, et al. Mapping of corneal layer thicknesses with polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography using a conical scan pattern. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(13):5579-5588.

15. Abusamak M. Corneal epithelial mapping characteristics in normal eyes using anterior segment spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2022;11(3):6.

16. Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Vida RS. Epithelial thickness mapping for corneal refractive surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2022;33(4):258-268.

17. Feng Y, Varikooty J, Simpson TL. Diurnal variation of corneal and corneal epithelial thickness measured using optical coherence tomography. Cornea. 2001;20(5):480-483.

18. Kanellopoulos AJ, Aslanides IM, Asimellis G. Correlation between epithelial thickness in normal corneas, untreated ectatic corneas, and ectatic corneas previously treated with CXL; is overall epithelial thickness a very early ectasia prognostic factor? Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:789-800.

19. Silverman RH, Urs R, Roychoudhury A, Archer TJ, Gobbe M, Reinstein DZ. Epithelial remodeling as basis for machine-based identification of keratoconus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(3):1580-1587.

20. Reinstein DZ, Gobbe M, Archer TJ, Silverman RH, Coleman DJ. Epithelial, stromal, and total corneal thickness in keratoconus: three-dimensional display with Artemis very-high frequency digital ultrasound. J Refract Surg. 2010;26(4):259-271.