Dry eye is a busy, noisy, and messy disease state. Since the time I was in training, several philosophical shifts have occurred to change how we think about and approach dry eye disease (DED). Advancing clinical expertise and diagnostics have also armed ophthalmologists with tools to better combat this complex disease. Here are some of my favorite pearls for this pursuit.

No. 1: Be on the lookout early. DED starts at a much younger age than previously thought, and it is important to catch it early in the disease process. In order to provide patients with a lifetime of comfortable eyes and high visual performance, inflammation must be stopped in its tracks.

No. 2: Consider the ocular surface of every refractive surgery patient. In refractive surgery patients, as with all surgical patients, it is essential to consider the inflammation burden. In the course of a normal preoperative workup, I evaluate the patient’s osmolarity, tear breakup time, and meibomian glands in addition to performing topography and aberrometry.

Additionally, a patient with DED is in chronic wound healing overdrive. This has an impact on the corneal nerve morphology, the epithelial cell density, and the eye’s ability to heal from the insult of surgery. By treating the ocular surface preoperatively, we can quiet the eye and enable the system to respond normally to wound healing. If we perform surgery in a patient with untreated ocular surface disease (OSD), we run the risk of elevating matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), which is implicated in the development of neuropathic pain. Inflammation must be addressed preoperatively to limit this risk factor.

I highly recommend using the ASCRS preoperative algorithm to address OSD in patients undergoing refractive (and cataract) surgery.

No. 3: Talk to your patients. You can learn a substantial amount about a patient’s ocular surface through effective communication and investigation. Embrace the need for SPEED, and utilize the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) questionnaire. There are just four simple steps to treating OSD: (1) use questionnaires to evaluate patients’ symptomatology; (2) assess the risk factors, including any medications that could be contributing to DED; (3) perform the appropriate diagnostics; and then (4) classify and treat OSD.

No. 4: See DED and MGD as a double vicious circle. Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is seen in more than 86% of DED cases. This number is misquoted often—MGD does not cause 86% of DED, but it is seen in the context of DED in 86% of cases. Back when I was in training, the thinking was: If the eye is dry, apply some artificial tears. But, as we know now, it is much more complicated than that. Inflammation is present, and that is our target. This has been another philosophical mind shift in DED.

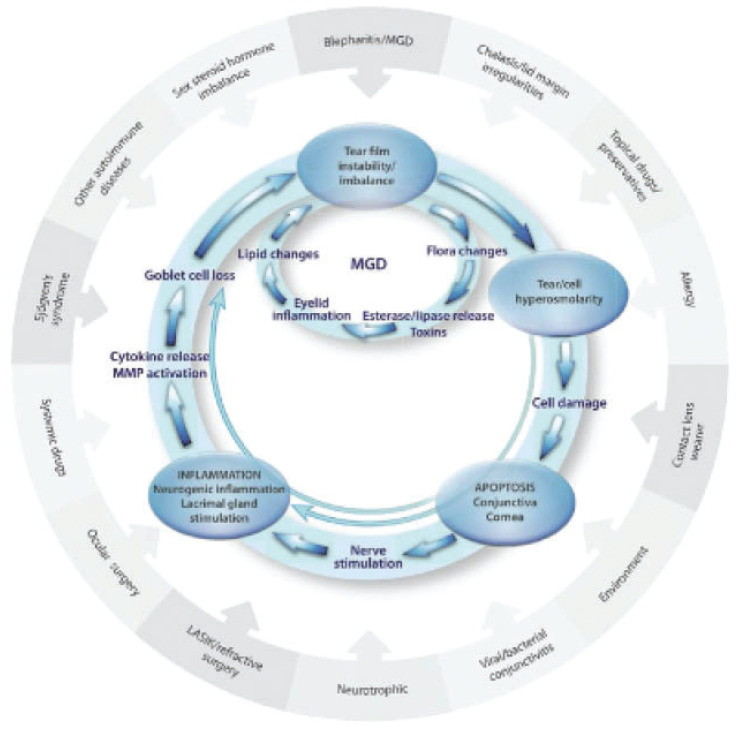

The Figure displays the vicious double circle of DED and MGD, and I use this image to counsel patients. On the outside are the risk factors that drive inflammation. In the middle, inflammation is driving MGD and aqueous deficiency. I no longer split these entities, nor do I separate aqueous and evaporative DED. This is unnecessary because it all comes down to inflammation. We must center our efforts on controlling inflammation. From there, we can spread out our philosophical construct and focus on the ultimate goal of restoring homeostasis and a healthy lacrimal functional unit.

Figure. The double vicious circle of MGD and DED.

No. 5: Prepare for a multidisciplinary approach. DED is a multifactorial disease that mandates a multidisciplinary treatment approach. When a thorough examination confirms that a patient has inadequate meibomian gland function, I look carefully for contributing factors (eg, Demodex, rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis) and organize my treatment approach around the six underlying and interrelated mechanisms of MGD. These mechanisms constitute what I like to call the MGD BEISTO—a six-headed BEISTO that laughs at warm washcloths! The six interrelated mechanisms include: Bacteria/bugs (microflora alterations and Demodex), Enzymes (the gene transcription and resulting proteins involved in the biochemistry of normal meibum production are abnormal), Inflammation (confocal microscopy demonstrates that activated T-cells surround the glands), Stasis of the meibum (poor quality and plugging), Temperature (abnormally elevates meibum melting temperature), and Obstruction (hyperkeratotic lid margins, terminal ductules, periductal scarring, etc). To slay all six heads of the BEISTO, all of these mechanisms must be considered. The interventions are combined until all six heads are addressed.

No. 6: Don’t lose the big picture. Look closely at each patient. Think beyond the slit-lamp findings and examine the skin and any local regional events that may be happening. Ocular rosacea, for example, is a known, common contributor to OSD. I perform a comprehensive examination. Age changes can alter eyelid position, eyelid mechanics, and midface support of the lower lids. I lift the lids and evaluate laxity. I pull the lids and push on the meibomian glands. I check the lateral canthal tendon integrity and look for symptom relief when the lid is positioned properly (as if evaluating the lid for a tightening procedure).

Additionally, consider the bigger picture—the whole patient. Think about the patient’s nutrition. Assess their beauty regimen, as bad beauty or hygiene practices can exacerbate DED. Be aware of the top offenders and know which cleaner alternatives to recommend. (For more on this topic, see my article, “Hair-Raising Issues in Eye Cosmetics,” in the August issue of CRST.) Screen the patient’s medication list and look for clues such as oral antihistamines, hydrochlorothiazide, and H2 blockers, which are DED-offending medications. Think systemically—use your MD background to see the bigger picture of DED. Your patients and their more comfortable, better-seeing eyes will thank you.