My Approach to Treating Dry Eye Disease

Our practice is a Center of Excellence for dry eye disease (DED) with an emphasis on external ocular diseases, corneal problems, and cataract and refractive surgery. My patients have often seen several other providers and tried multiple treatment options with little success before entering our office. For this reason, my standard approach to almost every patient with DED is to start from scratch and attack the disease from multiple angles—both to increase tear production and reduce inflammation. The most important step in the effective treatment of DED is accurately identifying the underlying problem(s). This entails asking the right questions and effectively explaining the nature of the condition to my patients.

I keep DED in mind as a possible explanation for any patient’s symptoms, even when their initial complaint does not point clearly to DED. An unhealthy ocular surface can cause vision fluctuations or poor distance vision in patients who have had cataract surgery. Knowing that the ocular surface can be repaired is key, but treatment may take up to 6 months or more before patients recognize results. The key is getting patients to adhere to the prescribed treatment.

My General Approach

My general approach to treating patients with DED is to start with a topical steroid dosed two times per day. I prescribe KPI-121 0.25% (Eysuvis, Kala Pharmaceuticals), loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel 0.5% (Lotemax Gel, Bausch + Lomb), or fluorometholone acetate ophthalmic suspension 0.1% (Flarex, Eyevance Pharmaceuticals). I also initiate therapy with an immunomodulator—cyclosporine (CsA) 0.05% (Restasis, Allergan), CsA 0.09% (Cequa, Sun Pharma), or lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 5% (Xiidra, Novartis)—and a preservative-free artificial tear, such as Oasis Preservative-Free Lubricant Eye Drops (Oasis Medical) or Refresh Optive Mega-3 Preservative-Free (Allergan).

I want to improve the health and function of the meibomian glands by prescribing topical azithromycin (Azasite, Akorn) to decrease inflammation and improve the quality of the meibum. I recommend the use of a hypochlorous acid spray, such as Avenova (NovaBay Pharmaceuticals) or Acuicyn (EMC Pharma) to decrease the bacterial load and/or presence of Demodex. Additionally, I prescribe oral omega-3 fish oil supplements, either Lovaza (Woodward Pharma) or Vascepa (Amarin). Finally, if I think it is indicated, I prescribe an oral antibiotic, such as tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, or oral azithromycin, to reduce inflammation.

Case Examples

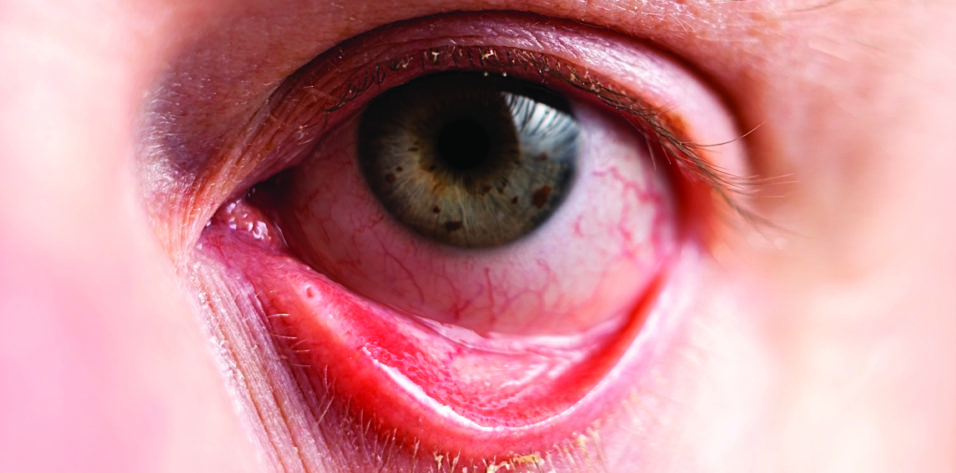

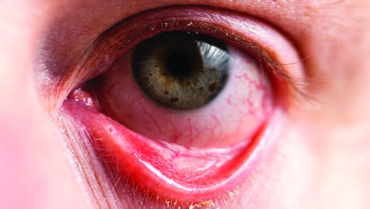

Patient No. 1. A 68-year-old woman presented for a DED evaluation after undergoing cataract surgery elsewhere. She reported having trouble reading, even while wearing multifocal glasses, and extreme discomfort. Her uncorrected distance visual acuity was 20/100, and her BCVA was 20/60. Conjuctival staining with lissamine green vital dye and corneal staining with fluorescein dye revealed severe ocular surface damage. The patient had a low Schirmer score and poor meibomian gland function.

I employed the standard approach I have described, and I instructed the patient to apply a lubricating ointment at night. At her 2-month follow-up examination, her uncorrected distance visual acuity was 20/40, and her BCVA was 20/25. She reported that her eyes were no longer red and that she no longer experienced ocular discomfort or difficulty reading.

Patient No. 2. A 40-year-old woman presented with contact lens intolerance after successful wear for many years. The patient had seen several other providers, none of whom could identify the cause of her discomfort. Keratoconus, however, was suspected.

The patient reported experiencing fluctuating vision, difficulty reading, intermittent redness, and ocular irritation with contact lens use. On examination, the corneal surface of each eye showed staining with fluorescein dye and the conjunctiva demonstrated lissamine green dye staining, which is consistent with severe dryness. The tear osmolarity was high, and her Schirmer score was low. She also had rosacea and meibomian gland dysfunction. Her BCVA was 20/25 with glasses and 20/40 with contact lenses.

I advised the patient to stop wearing contact lenses and initiated my standard treatment protocol to address the two components of her DED (ie, an unhealthy tear film and inflammation). I prescribed a topical steroid, an immunomodulator, and preservative-free drops for the inflammation. I also prescribed azithromycin, an oral omega-3 supplement, an oral antibiotic for her rosacea, and a hypochlorous acid skin spray.

NEW AND IN THE PIPELINE

CRST: What treatments, both in the dry eye disease (DED) pipeline and recently made available, are you the most excited about?

Gregg Berdy, MD: I find drugs that are in some way novel to be the most exciting. One example is Tyrvaya (varenicline solution nasal spray 0.03 mg, Oyster Point Pharma). It’s the first nasal spray approved by the FDA for the treatment of DED. This nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist stimulates the trigeminal parasympathetic pathway in the nasal cavity. I find the drug to be a great option for patients who are tired of instilling drops in their eyes or are unable to do so. The product is effective, in my experience.

An exciting drug in the pipeline is TP-03 (lotilaner ophthalmic solution 0.25%, Tarsus Pharmaceuticals). It’s being developed for the treatment of Demodex blepharitis. Before getting involved in the clinical trials for this drug, I didn’t think Demodex played much of a role in DED. I recognized, however, the lack of a real treatment for it other than hypochlorous acid spray, which doesn’t eradicate all of the Demodex. After getting involved in the research for TP-03 and seeing the data, I was pleasantly surprised to see that the lid margins became less inflamed when the Demodex were eradicated. It is still to be seen whether treating Demodex helps resolve meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) and blepharitis and thus DED.

Lacripep (Tear Solutions) is another example of an exciting drug in the pipeline. I have been involved in the research, and the results thus far are promising. It’s a peptide of the parent tear protein lacritin. The topical medication appears to promote tear production, restore the health of the ocular surface, and stabilize the tear film.

Beeran Meghpara, MD: There are so many products, both drops and procedures, in the DED pipeline. The key to treating DED is to control the inflammation because DED is an inflammatory disease. Long-term therapy with immunomodulators and autologous serum tears is effective in this regard. Many of the more recently available devices and the products in the pipeline focus on the eyelids—treating MGD and blepharitis. Increased awareness of the role the lids can play in DED is needed because, as more effective treatments become available, I expect DED management to become more multifaceted.

LipiFlow (Johnson & Johnson Vision) has been around for years. The availability of newer thermal devices such as TearCare (Sight Sciences) and iLux (Alcon) has brought attention to the role of the lids in DED. Each of these devices targets MGD. Some treatments may also have antiinflammatory properties. Intense pulsed light has been used as an off-label treatment for ocular surface disease for many years, but the OptiLight (Lumenis) is now approved by the FDA for the treatment of DED and MGD.

In the blepharitis space, Tarsus Pharmaceuticals is developing an investigational therapeutic, TP-03 (lotilaner ophthalmic solution 0.25%), for the treatment of Demodex blepharitis.

At her 2-month follow-up appointment, the health of the ocular surface had improved but remained suboptimal. At 4 months, she reported less discomfort. At 6 months, her most recent follow-up visit, she reported feeling much better and requested to start wearing contact lenses again. The ocular surface was healthier, but damage was still evident with lissamine green staining. I therefore advised her against resuming contact lens wear.

Beeran Meghpara, MD

Similar Presentations, Different Treatment Approaches

I find that asking the right questions is helpful when treating patients who present with DED flares. Patient responses help me better identify the problem and determine the best course of action. My contribution to this article describes two patients who presented with DED flares under different circumstances for whom my treatment approach differed.

Both patients were receiving long-term treatment for their DED with Restasis. Both reported worsening dry eye symptoms over the past year and showed signs of DED on examination. Their responses to my questions, however, elicited different approaches to treatment.

Ask the Right Questions

The first question I ask patients who present with a dry eye flare is whether they were ever satisfied with the control of their dry eye symptoms. If the answer is yes, a second adjuvant treatment modality may be warranted. If the answer is no, however, then it may be more helpful to switch to another option.

Next, I dig deeper into the specifics of their DED flare. I ask whether their eyes feel comfortable most of the time but their dry eye acts up now and then. If so, are there any identifiable triggers related to those flares? Do their dry eye symptoms worsen depending on the time of year, has their screen time increased owing to a work-related change, or do they take cross-country plane trips that exacerbate their DED? Alternatively, is their current exacerbation more chronic in duration and constant in nature?

Patient No. 1. Restasis had mostly worked well for this patient, but they started noticing worsening symptoms during the previous winter. They had also been working from home more, and their screen time had increased.

For this patient, the key for the treatment course was to resist the urge simply to add an artificial tear and instead try to reduce the ocular surface inflammation associated with this episodic DED flare. In these situations, I find a short course of topical steroids effective. Two options that I’ve had success with are Eysuvis and Flarex dosed three to four times per day for 2 weeks.

Patient No. 2. Restasis had worked well for this patient in the remote past, but they had been experiencing dry eye symptoms nearly every day for the past year.

A short course of steroid treatment was not the best approach to this patient given the chronic nature of their symptoms.

A different long-term treatment was more appropriate. One option is to switch to another immunomodulator, such as Cequa, which carries a higher dose of CsA than Restasis, or to Xiidra, which has a different active ingredient. An alternative approach in this situation is to transition the patient to autologous serum tears. Following a routine blood draw, the patient’s serum is separated and then diluted to a specified concentration, typically 20% to 25%. At this concentration, the autologous serum has a similar amount of epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor, nerve growth factor, and antiinflammatory mediators as found on a healthy ocular surface.

I have had good success in stabilizing and repairing the ocular surface in patients with autologous serum tears where other treatments have been ineffective. The drawback to serum tears is that they are inconvenient to obtain and are not typically covered by insurance. Vital Tears is a national compounding pharmacy that has streamlined the process and is trying to make serum tears a more accessible option.

Editors’ note: To read more about the ocular surface disease product landscape, click here.