As health care providers, we optometrists have an obligation to educate patients about their ocular health and the treatment options for their particular conditions. Yet there may be further benefits beyond the intrinsic value of the education itself. Patients tend to have better experiences and feel more confident in their providers when they leave an encounter knowing more than when they came in. In addition, providing good education helps patients connect with your practice and become familiar with your brand. Furthermore, having an informed patient base tends to lead to more efficient clinic operations.

Convincing eye care providers to think about patient education as a brand extension is not difficult once they realize the win-win nature of the endeavor: It is good for the patient and good for the practice. The difficulties most providers encounter lie in deciding what tools to use for patient education and learning how to use them effectively. This article details some of the methods we have found useful to offer patients the best information in the most helpful manner.

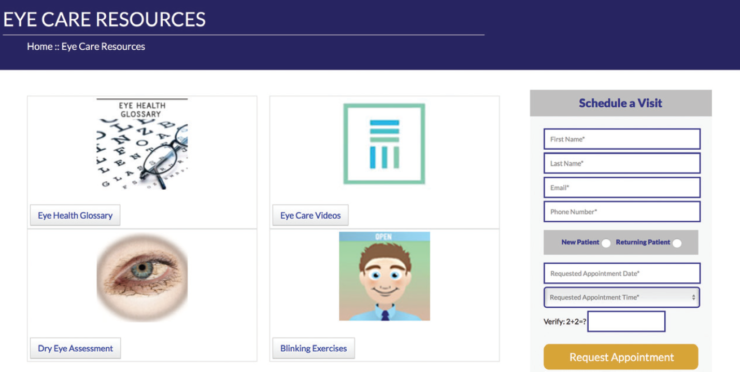

Figure 1. The practice’s website is a form of passive marketing.

AN ACCURATE PORTRAYAL

In our practice, we view our website as our most natural extension to the community, a form of passive marketing (Figure 1). A website should have a look and feel that is conducive to the brand one is trying to portray; in other words, a sloppy and carelessly put together website will tell the public that your practice shares those qualities. Perception is reality, whether we like it or not.

Patients do not want to be surprised when they come through the clinic door. Your website, in addition to being a brand extension, also has to offer an honest representation of the services provided by your practice and reflect your overall practice philosophy.

In the digital era, many people are familiar with the concept of “clickbait.” Some less-than-forthright content providers prompt users to click on a link based on an enticing headline, only to have the user arrive at a site that offers little in return. This practice is a variation on the old bait-and-switch technique, and it is used for the sole purpose of artificially inflating traffic to a website.

Those who fall victim to clickbait enticements feel duped and are reluctant to trust that source ever again. I mention this as an illustration of the dangers of offering patients something flashy on your website, only to have them enter your practice to find something completely different. When we are talking about ocular health, this is a subject infinitely more important than the latest angry cat meme. Therefore, the stakes are high for our websites to accurately portray what we intend to deliver.

DEALING WITH DR. GOOGLE

Also in relation to the Internet, it is worth considering the effect that our colleague Dr. Google can have on patient education and patient relations. The Internet is a wonderful place where patients can find information on just about anything, and that can be both a very good thing and a very bad thing. Too many patients are willing to self-diagnose, and any preconceived notion can be verified using a search engine.

It has been estimated that 85% of people using the Internet use Google to look for information, and more than 150 million health care–related searches are performed every day according to Yelp’s official blog and other sources. Eye care providers frequently encounter patients who enter the practice with their anticipated diagnosis already in hand, courtesy of Dr. Google. The question is, How do we address this when we encounter such a patient?

Every provider will have to figure out his or her own way to deal with this situation. I like to tackle the subject head on and to use levity to break the tension where necessary. I have developed a sense for when patients come into the practice after overusing the Internet. To break the ice, I make some comment about their having consulted Dr. Google before they consulted me. Then I try to disarm any preconceived notions by offering the patient better information.

I am not saying this approach will work for everyone. Each of us will approach the topic differently. Relating to patients is most effective when it is authentic. This simply encapsulates my approach to educating patients: I use humor to disarm and follow up by replacing misconceptions with reliable information.

EQUIPPING PATIENTS WITH GOOD RESOURCES

Anyone reading this article will relate to the scenario of the patient who comes into the office with a red eye and who is sure—absolutely convinced—that he or she has eye cancer. It can be a real drag to have to talk this patient off the ledge.

But flip the script for a second. Realize that this patient is going through a very natural process of trying to find an answer for a confounding problem. My best piece of advice when confronted with misinformation or misconception is to try to humanize the problem. Sure, it can be a time-suck to have to deal with sometimes wildly wrong assumptions. But then again, being misinformed is not a character fault. It just means the patient has not been introduced to the proper resources.

Part of providing patients with education is giving them a language they can use and understand. For example, I relate presbyopia to short-arm syndrome. I tell them that it is what their parents used to call “bifocal age.” That allusion does not tell the whole story, but at least it plants a picture in the patient’s mind. I can follow up on that with more information, tailored to the patient’s level of comprehension.

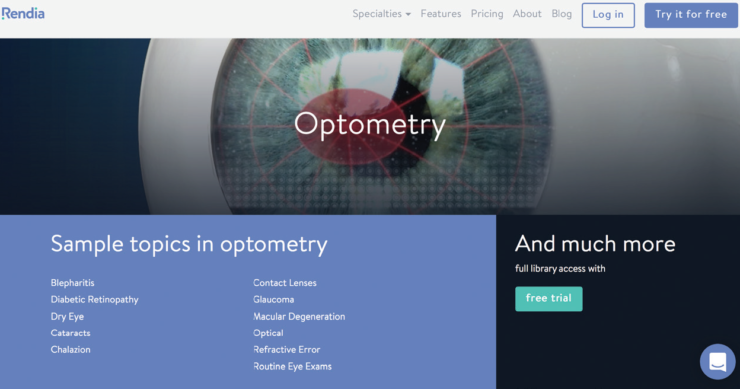

Figure 2. Video content serves as a helpful educational adjunct.

For providers who struggle to present patients with education, there are resources that can serve as adjuncts. For instance, we make ample use of Rendia (formerly Eyemaginations) video content (Figure 2). This company creates exceptionally well-produced and informative education videos and information pieces spanning a plethora of ocular conditions. Such tools can serve as a bridge to connect with patients.

MAKING THE CONNECTION

I believe that optometrists should make every effort to provide patients with the information they need to participate in their own care, which, in turn, offers them the best chance for a successful outcome. However, there may also be situations where the connection fails. I am reluctant to do so, but there have been times (rarely) when I have suggested to patients that they find another provider because they just do not seem to be accepting the information I am providing. It is a difficult decision to turn a patient away, but, ultimately, it may be in the best interest of that patient to do so. Perhaps there is another provider out there who can make that connection that I could not.

I am sure that all of us can do a better job of communicating with and educating patients, and this may be an area that is ripe for new innovations and technologies to help us. Beyond all of that, providing for the ocular health of our patients is ultimately a people business. If we focus on putting the needs of our patients first, finding ways to communicate with them becomes a lot easier.