Maintenance of Certification (MOC) has recently become a cause célèbre throughout medicine. MOC is just one of several burdens of dubious value with which physicians are saddled in the name of quality. Physicians must also satisfy the demands of interested parties, including Medicare, private insurance companies, and various consumer and patient advocacy groups. Meanwhile, doctors must also satisfy measures for the Physician Quality Reporting System (commonly known as PQRS) and the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (commonly known as ICD-10), which are codified within Medicare law and the Patient Protection and Affordability Act. If not the most onerous of the demands, MOC is at least the most immediate one and offers the best opportunity for alternative means of compliance.

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) is made up of 24 member boards. Its mission is to serve the public interest and promote excellence in the practice of medicine.

Physicians who completed board certification prior to October 1, 1994, were granted lifetime certificates. For diplomates seeking initial board certification after this date, time-limited certificates were issued, and the ABMS mandated recertification for these individuals. As such, after 10 years, physicians were required to take a recertification examination in addition to meeting the usual continuing medical education (CME) requirements to maintain an active medical license. In 2007, the ABMS mandated that the recertification programs of its subsidiary boards transition to what today is referred to as Maintenance of Certification programs.1 In addition to the 50 to 100 hours of CME required every 2 years (by most states) and a recertification written examination every 10 years at a cost of over $1,500 to physicians, the ABMS added other requirements for MOC, including the so-called self-assessment modules (and Improvement in Medical Practice modules.

According to the ABMS website, “the change from recertification to MOC strengthened the program and guaranteed that physicians were current in ways not immediately available for testing.” At the same time, the ABMS determined that these standards should not apply to diplomates who had completed board certification prior to October 1, 1994, thereby holding “grandfathered physicians” to a lower standard than the rest of their peers. Many of the older physicians, who are many years out of their residency training, may be among the ones who are the least up to date on current practice.

MOC is at best a dubious concept with unclear goals. What the public and physicians alike want to ensure is that all professionals charged with maintaining and protecting the health of patients are competent at what they do. The initial board certification process has traditionally been an attempt to do just that—to show that a board candidate can demonstrate a basic competency as a physician in his or her chosen field. On the other hand, the current ABMS MOC requirements do not and cannot ensure that a practicing physician has maintained his or her competency to practice medicine. The ABMS acknowledges this concept. In fact, one ABMS member website has included the following statement: “Many qualities are necessary to be a competent physician, and many of these qualities cannot be quantified or measured. Thus, certification is not a guarantee of the competence of the physician specialist.” In other words, board certification is meant to demonstrate competence, but the board does not want to guarantee competence.2 This concept also nullifies the notion that the American College of Physicians raised, that if you become involved in litigation, board certification will somehow protect you.3 The fact is that, if you are negligent, no piece of paper hanging on your wall will protect you.

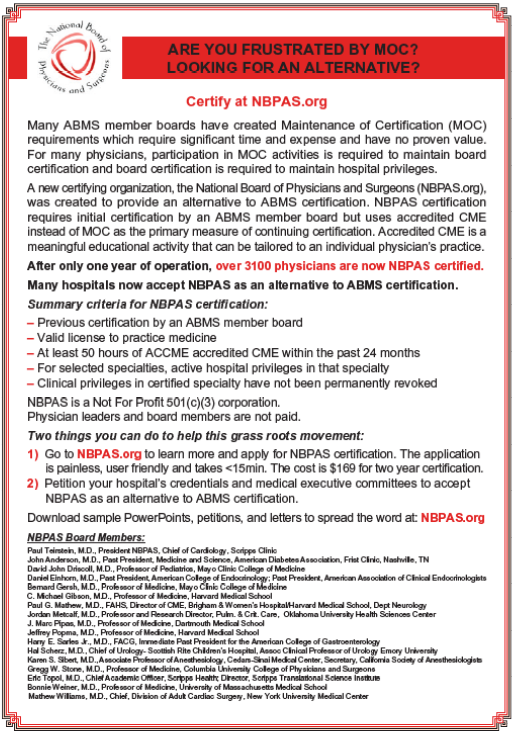

Figure. An ad by the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS) appearing inThe New England Journal of Medicine.

The ABMS requirements for MOC are arbitrary and untested. The costs to practicing physicians are considerable, in terms of both time and money to complete this process. In a recent study, a physician’s compliance with MOC was found to cost anywhere from $23,607 to $40,495 over a 10-year period depending on specialty,4 yet there is no published evidence to show that any of these requirements except for CME serves to improve quality of practice on an individual basis. No one would argue that CME is irrelevant, and most states require CME (25-50 hours of accredited CME per year) for maintenance of licensure.

CRITICISM, CONTROVERSY, AND PUBLIC PERCEPTION

Over the past year, much criticism has been directed against MOC, and there is some evidence that the issue has begun to take hold publicly. For example, in a recent overview of the MOC issue published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Paul Teirstein, MD, chief of cardiology at the Scripps Clinic in San Diego, criticized the financial aspects of MOC as they apply to the ABMS and its subsidiary boards, including the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).5 Shortly after this article appeared, the ABIM issued a “mea culpa” and suspended some of the practice assessment, patient voice, and patient safety requirements for at least 2 years.6

The topic of MOC has reached the lay media as well. Newsweek’s Kurt Eichenwald has written multiple pieces on MOC that cover problems with board certification as well the salaries, bonuses, and luxurious perks that the ABMS has been awarding itself at the expense of its diplomates.7,8 In response, the ABIM accused Mr. Eichenwald of being biased because he is married to a physician.9

The public perceives correctly that there are major problems with medicine and our health care delivery system, but the causes and the solutions are often misidentified. Ironically, the proposed solution to add more unnecessary administrative and regulatory requirements to an already labyrinthine system compounds rather than mitigates the problems.

When physicians are encouraged—even forced—by the system to spend no more than 15 to 20 minutes with a patient, much of which time already consists of checking off senseless bullet points on an electronic health record screen, all the up-to-date knowledge in the world is not going to help them provide better care. Patient advocacy groups and politicians, however, do not appear to understand this concept.

The other unfortunate irony is that relicensure and recertification burdens will not likely weed out the bad actors but rather may serve to annoy and frustrate the good ones. The challenge is to educate the public and the patient advocacy groups on what should be done to reduce the inadequacies they perceive in the system (some of which are very real) rather than to accede to their poorly conceived remedies for problems they do not really understand. To charge them with making medical policy is like asking a physician to instruct a mechanic on how to repair car brakes. Such instruction may be well intentioned, but it will likely result in the car’s being unsafe to drive.

A NEW PATHWAY

Fortunately, there is a viable alternative to the ABMS pathway to MOC. The NBPAS, which was started by Dr. Teirstein, is offering recertification in select medical specialties. The board of directors of the NBPAS comprises members representing many of the country’s top clinics, academic institutions, and specialty organizations (Figure). All physician members and directors of the NBPAS are volunteers (there is a small paid administrative staff), whereas members of the ABMS and its member boards are paid in six-figure dollar amounts annually.

The NBPAS has established the following criteria (NBPAS.org) for its recertification:

•Previous certification by an ABMS member board

•A valid license to practice medicine

•At least 50 hours of Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education-accredited CME within the past 24 months (physicians-in-training are exempt)

•Active hospital privileges (for select specialties)

•Clinical privileges in certified specialty have not been permanently revoked

The fee is $169 for 2-year certification, not including the cost of obtaining CME credits.

The MOC requirement itself is incorporated in Medicare law and under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, although there is ambiguity regarding whether MOC must be obtained via the ABMS specialty boards. When these laws were written, the ABMS was essentially the only game in town for physicians. The ABMS has been challenged as a monopoly organization for specialty certification and recertification. Presumably because of this, or perhaps as a pre-emptive defense, the ABMS recently publicly acknowledged that it does have competition in the form of the NBPAS. To punctuate this point, one ABMS member website included the following statement: “Possession of a board certificate does not indicate total qualification for practice privileges, nor does it imply exclusion of other physicians not so certified.”2

Due to pressure from NBPAS and others, the ABMS boards have had to reconsider their position on MOC. Beginning in 2016, the American Board of Anesthesiology decided to discontinue its 10-year recertification examination. Instead, this board’s diplomates will be taking an online 30-question quiz per calendar quarter (120 questions per year). Many of the previous requirements remain in place. Although this is a step in the right direction, one must assume that a 120-question, online, open-book examination for all recertifying diplomates is significantly cheaper to produce and administer than a secure 10-year examination. That said, the cost of this new MOC program is $210 per year instead of a lump sum of $2,100 to take the closed-book examination every 10 years.10,11 Clearly, the boards feel a reduction in cost of production should not translate to a decrease in cost to the diplomates, so the boards should actually generate even greater revenues.

THE FUTURE OF BOARD CERTIFICATION

Despite the minor progress I have seen, I have voiced my concerns to ABMS leadership.

Meaningful MOC reform should include all of the following:

•Removing the 10-year recertification examination

•Lowering the cost of MOC if a quarterly online question format is put in place. Keeping the same fee structure would be ridiculous, because the expense to the ABMS is much smaller than for generating and administering a 10-year examination.

•Participants should receive CME credit for completing these online modules

•Removing unnecessary, cumbersome, and unproven modules

•Basing recertification primarily on CME and a clean practice record

The ABMS boards acknowledge that the NBPAS exists as a legitimate alternative board, but they do not feel threatened.12 They are confident that physicians will blindly continue to pay to do unnecessary work in the name of board certification.

Unfortunately for the ABMS boards, more physicians are starting to understand that there is now another pathway to recertification. More than 3,000 physicians have become diplomates of NBPAS, which has become accepted as a viable alternative to ABMS by an increasing number of hospital credentialing departments. It is only through an expanding number of diplomates that NBAPS can increase its acceptance and rival the inflexible, self-centered monopoly that ABMS has become. In order to attract more diplomates, a full-page advertisement (Figure) will be featured in the New England Journal of Medicine in four editions.

Over time, the NBPAS should grow in terms of certificates granted. Moreover, the number of hospital credentialing committees that accept NBPAS as a viable alternative for maintenance of board certification will likely increase as well. With more institutions accepting NBPAS certification, the influence and leverage of the NBPAS will grow, and physicians will be relieved of the burden of complying with costly and time-consuming requirements that do not improve practice. It might even force the ABMS to revise its own requirements for MOC. Ultimately, it is up to the individual physician to decide whether it is to his or her advantage to take a stand on MOC based upon principle. There is no harm in being dual boarded, and becoming a diplomate of the NBPAS prior to the expiration of an ABMS board certification is a low-risk decision that supports a pro-physician grassroots movement. During this time of unprecedented physician unity, organizations like NBPAS appear well positioned to help return the practice of medicine to physicians rather than detached administrators.13

1. The mission and history of the ABPN. https://www.abpmr.org/consumers/consumers.html. Accessed February 16, 2016.

2. What is the ABPMR? https://www.abpmr.org/consumers/consumers.html. Accessed February 16, 2016.

3. ACP letter to members. http://www.acponline.org/education_recertification/recertification/moc_email_to_members_2.20.15.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2016.

4. Sandhu AT, Dudley RA, Kazi DS. A cost analysis of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Maintenance-of-Certification Program. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):401-408.

5. Teirstein PS. Board to the death—why maintenance of certification is bad for doctors and patients. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:106-108.

6. ABIM announces immediate changes to MOC program. February 3, 2016. http://www.abim.org/news/abim-announces-immediate-changes-to-moc-program.aspx. Accessed February 16, 2016.

7. Eichenwald K. The ugly civil war in American medicine. Newsweek. March 10, 2015. http://www.newsweek.com/2015/03/27/ugly-civil-war-american-medicine-312662.html. Accessed February 16, 2016.

8. Eichenwald K. Medical mystery: making sense of ABIM’s financial report. Newsweek. May 21, 2015. http://www.newsweek.com/medical-mystery-making-sense-abims-financial-report-334772?rel=most_read3. Accessed February 16, 2016.

9. Eichenwald K. A certified medical controversy. Newsweek. April 7, 2015. http://www.newsweek.com/certified-medical-controversy-320495. Accessed February 17, 2016.

10. ABA. About MOCA 2.0. http://www.theaba.org/MOCA/About-MOCA. Accessed February 16, 2016.

11. ABA. MOCA 2.0 FAQs. http://www.theaba.org/PDFs/MOCA/MOCA-2-0-FAQs. Accessed February 16, 2016.

12. ABPN News and Announcements. http://www.abpn.com/about/news/). Accessed February 16, 2016.

13. The BMJ. Elizabeth Loder: Has the American Board of Internal Medicine lost its way? March 19, 2015. http://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2015/03/19/elizabeth-loder-has-the-american-board-of-internal-medicine-lost-its-way. Accessed February 16, 2016.

Paul G. Mathew, MD, FAHS

• member of the Harvard Medical School Faculty and director of continuing medical education at the Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Department of Neurology, John R. Graham Headache Center, Bostonbr

• staff neurologist at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates and the Cambridge Health Alliance in Eastern Massachusetts

• neurology representative on the volunteer Advisory Board of the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons

• chief medical editor of Practical Neurology

• pmathew@partners.org