I learn from surgeons around the world every day!

Uday Devgan, MD, FACS

Ophthalmologists begin with a foundation of knowledge laid during residency and fellowship, and then we spend a lifetime building on that. The only constant in ophthalmic surgery is change, and our techniques and technologies evolve every year. If we perform surgery using only the methods we learned during residency training, we will soon find ourselves behind the times.

One of the best sources of cutting-edge surgical information is our fellow surgeons, and the best way to learn from them is to observe them in the OR. Two decades ago, I was fortunate to travel to more than 50 countries and 36 US states to learn from other surgeons, give lectures, and perform demonstrations. Over the course of many years, I learned from the best surgeons in the world, but the experience came at a cost: I was away from my own practice for 2 to 3 months per year, and I had to travel more than 1 million miles. Nevertheless, it was the best fellowship that I can imagine, and I brought newly learned surgical techniques back to my practice in Los Angeles for the benefit of my patients.

AN EVOLUTION IN LEARNING

I learned surgery from my excellent mentors at the University of California at Los Angeles Jules Stein Eye Institute and from other surgeons around the world via the Video Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery from Robert H. Osher, MD, (for more on this and other online surgical video resources, see Online Video Education Resources). As a resident, I searched far and wide to find VHS tapes of these videos so that I could study them carefully. Now, they are available on Eyetube.

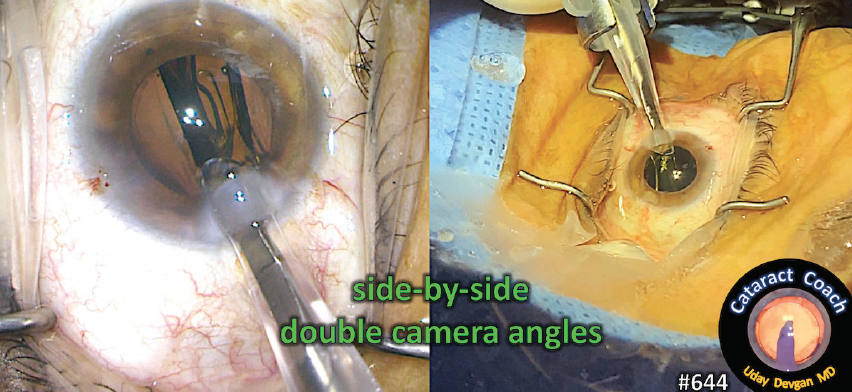

It’s a new world. Instead of low-resolution Super VHS, videos are recorded in high-definition or even 4K, and they can be watched on a mobile phone virtually anywhere in the country. Currently, my preferred way of learning surgery is to watch surgical videos. Although they are filmed mostly from the surgeon’s view through the operating microscope, many use two camera angles and show the external view (Figure 1). This is as good as being there in person. Even if I visit a center, I watch the surgery on a video monitor in the OR because I do not have privileges to scrub into the cases.

Figure 1. This is an example of the double–camera-angle videos that show the surgeon’s view through the microscope and the external view simultaneously. This creates a better learning experience and is as good as being there in person.

Three years ago, I started CataractCoach.com, which is a free surgical teaching website. It features a new video every day and is approaching video number 1,000. These are all categorized and indexed, and there is a powerful search engine that makes navigating the videos and finding a particular topic easy. In the past month alone, I have learned from dozens of ophthalmologists worldwide and in the United States on this website. Each of them has taught me an important surgical pearl that ultimately benefits my patients. The best part is that each video is just 5 minutes long.

THE POWER OF PEER EDUCATION

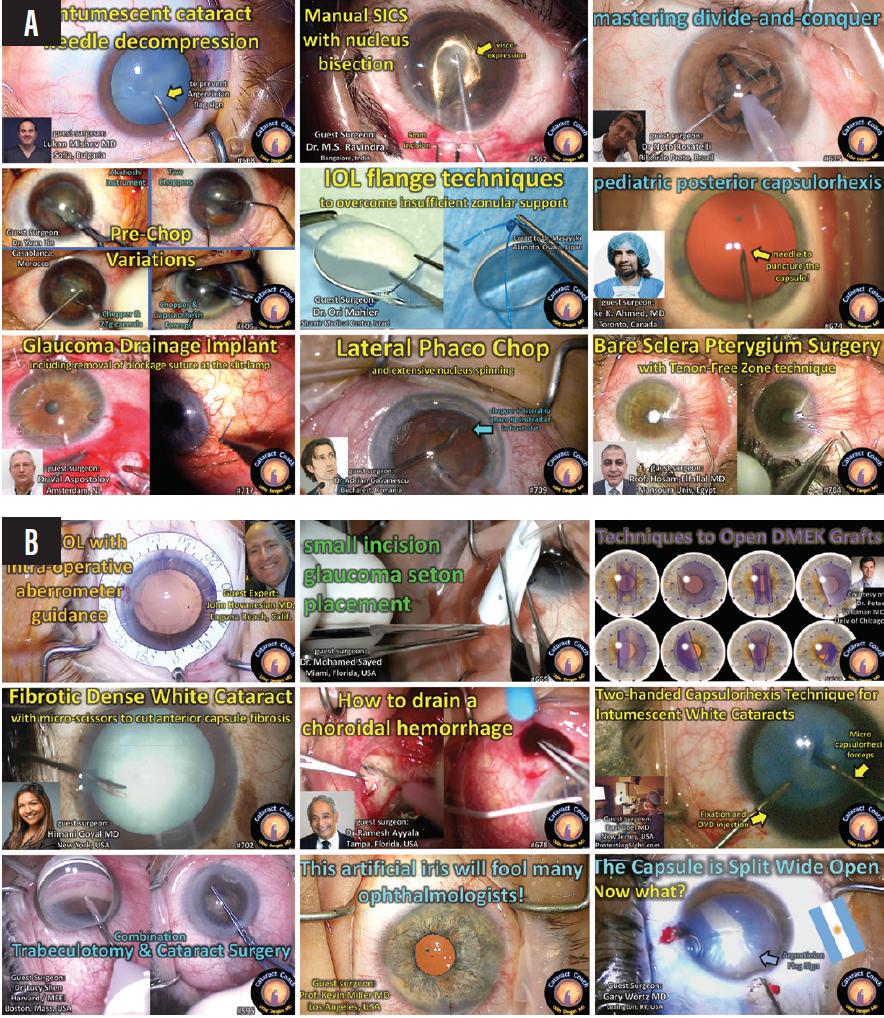

My surgical skill set has benefitted from watching my peers, both live and on video. Below is just a handful of surgeons who I have learned from by watching their videos (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Colleagues from outside (A) and within the United States (B) have taught Dr. Devgan and others so much about ocular surgery from their videos on CataractCoach.com.

Figures 1 and 2 courtesy of Uday Devgan, MD, FACS

International Colleagues

- Lukan Mishev, MD, from Bulgaria, is a master surgeon who often livestreams his cases to a worldwide audience. He taught me the art of decompressing intumescent white cataracts with a needle.

- M.S. Ravindra, MD, MBBS, from India, showed me the technique of manually bisecting the nucleus while performing manual small-incision cataract surgery.

- Neto Rosaelli, MD, from Brazil, has mastered just about every cataract surgical technique, and it is a pleasure to learn from him.

- Yan Lin, MD, from Morocco, has taught me multiple prechop variations and showed me that even a blunt cannula can split a nucleus.

- Ori Maher, MD, from Israel, is the king of IOL flange techniques, and I have learned a lot from watching his cases.

- Iqbal Ike K. Ahmed, MD, FRCSC, from Canada, showed me how to succeed in pediatric cataract cases that require a posterior capsulotomy.

- Val Apostolov, MD, from the Netherlands, is a truly gifted surgeon, and I have improved my surgical technique in glaucoma cases by observing him.

- Adrian Gavanescu, MD, from Romania, showed me that the chop technique could be lateral instead of just linear.

- Hosam El-Fallal, MD, from Egypt, showed me how to improve pterygium surgery by creating a Tenon-free zone.

Colleagues in the United States

- John Hovanesian, MD, from Laguna Beach, California, is an outstanding surgeon who taught me when he was a cornea fellow and I was an ophthalmology resident at the University of California at Los Angeles more than 20 years ago. He still teaches me with every video he makes.

- Mohamed Sayed, MD, from Miami, showed me that it is possible to place a glaucoma seton device through a small incision, something I had never seen before.

- Peter Veldman, MD, from Chicago, has made me better at Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty by showing all of the graft configurations and how to solve the unfolding dilemma—pure genius.

- Himani Goyal, MD, from New York City, showed that anterior segment surgeons can use retinal instrumentation for tough cataract cases.

- Ramesh S. Ayyala, MD, from Tampa, Florida, taught me how to drain the blood from a choroidal hemorrhage. Although I have not yet encountered this complication, I am now prepared to deal with it.

- Ravi D. Goel, MD, from Cherry Hill, New Jersey, showed that using both hands during a challenging case will allow me to fixate the eye and inject an OVD while performing the capsulorhexis.

- Lucy Q. Shen, MD, from Boston, taught me the nuances of concurrent glaucoma and cataract surgery. I consider her surgical technique to be among the best on the planet.

- Kevin M. Miller, MD, works down the street from me in Los Angeles, but I have not visited his OR since the culmination of my residency. His video showed me a brilliant technique for artificial iris implantation.

- Gary Wörtz, MD, from Lexington, Kentucky, showed me a technique for successfully completing cataract surgery and achieving an excellent visual outcome despite being surprised by the Argentinian flag sign.

Conclusion

Traveling thousands of miles to watch another surgeon in the OR or to hear another surgeon speak at a large ophthalmology meeting seems increasingly inefficient. The future of ophthalmic surgical education is streaming videos online. We can watch these videos whenever we want and review them before our own similar surgical procedures. The most important beneficiaries of this education are our patients.

I learned a lifetime of lessons by visiting Joseph Colin, MD.

Aylin Kiliç, MD

I’ve always been interested in helping patients with keratoconus. Early in my career, there were many young, usually hopeless patients with this disease visiting my clinic. (Corneal transplantation cannot be scheduled within a short time in my country.) These patients were often contact lens intolerant and navigating life with difficulty because they were unable to see clearly. Around that time, the idea of changing the corneal shape using an intrastromal corneal ring segment (ICRS) was an exciting one. It was a creative approach: The nomogram was not clear, and there were so many aspects of the procedure to discuss and consider.

Figure 3. Drs. Kiliç and Colin at an American-European Congress of Ophthalmic Surgery meeting in Cannes, France, in their last photograph together before Dr. Colin’s death in 2013.

Courtesy of Aylin Kiliç, MD

In 2007, I was introduced to Joseph Colin, MD (Figure 3), by Jose Luís Güell, PhD. I was full of questions about how ICRSs work. Dr. Colin invited me to visit his clinic in Bordeaux, France. I gave my first international talk about femtosecond lasers at his university. It was an important topic for me because I was planning to perform ICRS surgery using a femtosecond laser. My visit to Dr. Colin’s practice was so helpful. He explained many details of the procedure and answered all of my questions. I watched him perform an ICRS operation and peppered him with questions about tunnel size, ring size, astigmatism management, tunnel depth, indications, and the importance of the ICRS. He graciously answered them all.

At that time, PMMA was being used for ICRSs. Dr. Colin told me, “The cornea never accepts a foreign body. There will be rejection.” Afterward, I focused on finding a way to change corneal shape naturally—without implanting a foreign body.

The lessons I learned from Dr. Colin were not limited to keratoconus treatment. I also learned from him how to write articles for a peer-reviewed publication. We coauthored a clinical article and a review article together.

Dr. Colin was not only a good surgeon. He was also an outstanding scientist, organizer, and teacher. I learned how to be a better leader by observing his relationship with his team, and my visit led me to realize how valuable teamwork and the support of young ophthalmologists are for our specialty.

Thank you so much, Dr. Colin. I continue to follow your advice, and I will follow your example always.

Observations in colleagues’ ORs have been the impetus for paradigm shifts throughout my career.

Tal Raviv, MD

Pursuing a path in private practice medicine has its challenges, especially in this era of corporate medicine, ever-present regulatory and compliance hurdles, and market consolidation. To me, however, this path offers unrivaled independence and full authority—the ability to build a practice best suited for myself and my fellow doctors, our staff, and, most important, our patients.

Look to Others

It is important for anyone aspiring toward private practice to seek the advice, guidance, and inspiration of colleagues, industry experts, consultants, nonmedical professionals, and entrepreneurs. Advice can come in many forms. Nothing, however, has as great an impact as a direct conversation, which often takes place informally—sometimes serendipitously—in and around ophthalmology meetings. It’s one of the things I miss most in this year of virtual gatherings.

The most elevated and immersive type of direct conversation one can have with a fellow surgeon occurs when visiting their practice. Seeing them in their environment and having access to them in their zone is an unparalleled learning experience. Several surgeon visits, in particular, have been influential on my career path.

important Early Visits

I can think of several early experiences that helped to shape my medical career.

High school. My first time in an OR was a visit to a vascular surgeon in private practice, Herbert Dardik, MD, during a high school summer observership. I was young and impressionable, and those few weeks with him planted the seeds of my future surgical career. Dr. Dardik practiced in a standalone office building on what was called doctor’s row across the street from our local hospital. I remember following him from the clinic to his vascular lab to the OR. As busy as he was, he loved every minute. It seemed like a great life path to follow.

I recently read of Dr. Dardik’s passing and learned that his infectious spirit and positive attitude had influenced hundreds of residents, fellows, medical students, and even high school students like myself. He was a super spreader of the value of a medical career in the best possible way.

Residency. My next paradigm-shifting surgeon visit occurred during the third year of my ophthalmology residency at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary (NYEEI). At the time, refractive surgery was in its infancy. LASIK was just taking off, and many community ophthalmologists were seeking certification in PRK. A voluntary faculty attending who had eagerly incorporated LASIK into his private practice, Barrie D. Soloway, MD, allowed us third-year residents to shadow him in the office and watch him operate. If we brought our own cases, he even promised to proctor us—and he did.

These were the days of manual microkeratomes when operating on an eye with 20/20 VA was considered heresy by many. But thanks to the forward-thinking of Dr. Soloway and the NYEEI’s residency program directors, the residents collectively performed more than 70 LASIK procedures in a single year. I subsequently decided to seek out a cornea/refractive fellowship.

Fellowship interview. Also in my third year of residency and early in my learning curve with phacoemulsification, I interviewed for a fellowship with Richard L. Lindstrom, MD. I quickly realized that the interview process at Minnesota Eye Consultants was not like at other academic institutions. I toured the facility with one other applicant, and then we followed Dr. Lindstrom; David R. Hardten, MD, FACS; and Thomas W. Samuelson, MD, as they floated from clinic to OR to LASIK suite, each of which was just a hallway away. They were also writing articles, planning meetings, preparing talks, and doing research—all while in private practice. Finally, I was ushered into the OR to observe Dr. Lindstrom perform cataract surgery. I remember standing in the corner and looking up at the clock at the start of surgery; it was just a few minutes before the hour. I watched Dr. Lindstrom casually yet exactingly proceed with a topical clear corneal procedure using a supracapsular tilt and tumble technique. The IOL went in, and he slowly stood up, removed his gown, and left the OR to see the next patient in clinic before beginning another procedure. When I looked back up at the clock, it was still a few minutes before the hour.

I ended up taking a fellowship in Chicago the following year, but the rest of my third year changed for me after that visit to Minnesota. I had seen how cataract surgery should be performed, and I went all-in on topical, clear corneal, supracapsular cataract surgery. My goal was to perform the perfect procedure, Lindstrom-style. By year’s end, thanks to the guidance of my NYEEI attendings, I was well on my way.

Getting Started

Over the course of my first decade in practice, I worked on becoming the best surgeon I could. I took on the most challenging cases so that they became almost second nature. I recorded my surgeries, wrote papers, and started delivering presentations at ophthalmology meetings, all while delving into and studying the abundance of new technologies in our specialty. As an early adopter of new technologies, surgeons would visit me in the OR to watch a new device or technique in action. Regretfully, however, I hadn’t made visiting other surgeons a priority yet.

In my early years in practice, I visited the elite Manhattan practice of Nancy H. Coles, MD, who has built one of the most reputable independent practices in the city. Dr. Coles treats her patients like family—greeting them with hugs and personally conducting the workup and examination. Her office is a cross between an art museum and a graciously decorated parlor or living room. Being independent of commercial insurers, Dr. Coles gives her patients unparalleled access, unhurried encounters, and personalized attention that many of us could only dream of offering. This was a cutting-edge surgical practice that Dr. Coles imbued with an old-world charm and attention hard to find in medicine today. Visiting her practice left me with a beautiful vision of what health care could and, I thought, should be like.

Building My Own Practice

When I started my own practice, I began thinking proactively about visiting surgeons in other parts of the country. Building a boutique refractive practice in Manhattan kept me busy, and over a short couple of years, it had grown too big for the space that we had renovated. I had to decide the type of practice I envisioned—mainly the scope of that practice, its physical size, and the number of locations. Visiting colleagues proved an invaluable source of guidance for me in that process.

I visited my good friend David A. Goldman, MD, a top cornea and refractive surgeon who had just moved into his own brand-new clinic, Goldman Eye, which he built to his specifications from scratch. It was beautifully designed for great patient flow and exuded innovation. He invested in the sleekest examination lane equipment, which wasn’t inexpensive, but, boy, did it look and feel good. He was the king of his castle, and I returned to my practice feeling emboldened to chart my own path toward a bigger location.

Most recently, I visited Steven J. Dell, MD, who has been a guru to many of us. He has also built a world-class cataract and refractive practice focused exclusively on surgery and associated conditions such as dry eye disease and keratoconus. I saw that his practice was at the forefront of anterior segment surgery, complete with every existing and emerging technology, in one beautiful, high-end clinic. As I walked in, the waiting room felt more like a combination of a luxurious living room, hotel lounge, and library. He told me that he had hand-selected every book because it had significance to him, which I noticed served as a conversation piece with patients.

As we sat in his office and chatted, I shared where I was in my practice journey. He asked me if I liked doing surgeries and if I would like to do more. When I nodded affirmatively, he broke the news to me, “You can’t grow both a general and a refractive cataract surgery practice simultaneously.” To achieve what I desired, he explained, I would have to focus relentlessly on my surgical patients. As for my current general ophthalmology patients, Dr. Dell’s advice was to gradually schedule them out of my lane and into the lanes of other nonsurgical providers in the practice. Eventually, perhaps these patients would be scheduled out of the practice entirely. It sounded dramatic, but it was true.

We also talked about the importance of the look, feel, and location of a practice. I had been eyeing a potential prime space on the desirable Upper East Side of Manhattan. Of course, this location had a steeper cost and was also a raw space, requiring a full build-out, including HVAC, plumbing, and electricity. Dr. Dell challenged me to think of a good reason not to move to the best space I could find. Why wouldn’t a world-class refractive surgery center be in a prime location?

Putting It Into Practice

Upon my return home from Dr. Dell’s practice, my path became clear. I built out the space in the prime location and designed every room, office, and hallway with form and function front of mind. I maximized the design to allow patient comfort, happiness, and privacy—all with a view. Patient and staff flow would be seamless, and the latest best-in-class equipment would always be invested in. We successfully moved into our new, spacious, uptown office in August (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Dr. Raviv and his team at their clinic in Manhattan.

Courtesy of Tal Raviv, MD

Although COVID-19 and the related shutdowns certainly affect us, as they have all of ophthalmology, I am happy to report that I am exclusively seeing cataract surgery, MIGS, and LASIK patients. With a more focused schedule, I can devote more time and attention to each surgical patient. I can get to know them and guide each of them to their best refractive solution. The practice’s other doctors also manage tertiary dry eye with advanced diagnostics, intense pulsed light, and vectored thermal pulse therapy (LipiFlow, Johnson & Johnson Vision). Stable postoperative patients without primary eye care providers are referred to community optometrists for long-term care. I am now even closer to my goal of providing the ultimate hospitality-focused patient experience.

Conclusion

Looking back, I realize how important visiting other elite surgeons has been in shaping my career path. Thank you to all those I have had the opportunity to visit and learn from, and I look forward to visiting many others in the future. To those who have already or will someday visit me, I hope to inspire you, too.

Online Video Education Resources

By Michele Corry, Associate Editor

Eyetube.net

Launched in 2008, Eyetube.net revolutionized the format of education in the ophthalmic world and has become a go-to resource for on-demand skills transfer powered by original, physician-generated content. The Video Journal of Cataract, Refractive, and Glaucoma Surgery from Robert H. Osher, MD, is also housed on and accessible via Eyetube.net.

YouTube

This expansive online video-sharing platform launched in 2006. It allows users to upload, view, rate, share, report, and comment on videos; add videos to playlists; and subscribe to other users’ channels. Like Eyetube.net, YouTube is a popular and easily accessed hub where ophthalmologists around the world can upload and share videos of surgical techniques and skills with their ophthalmic colleagues.

Resources From Professional Organizations

Many professional organizations offer educational video content on their websites. Popular examples include the AAO’s Clinical Education Video Resource and the ASCRS’ Clinical Education Search, which both house hundreds of educational surgical videos.