Neurotrophic keratitis (NK) is a degenerative corneal disease resulting from the partial or total impairment of trigeminal innervation.1 A wide array of systemic and ocular causes have been implicated in the pathogenesis of NK. On physical examination, later-stage NK appears as epithelial defects that may be confused with other eye diseases, including dry eye, exposure keratitis, topical drug toxicity, contact lens abuse, and corneal limbal deficiency; however, symptoms are often absent, as a loss of corneal sensation is a hallmark characteristic.2 Thus, identifying NK early can be challenging yet important, as the progression to later stages of NK is associated with stromal involvement, with an increased risk for developing corneal ulcer, melting, and perforation.3

Background

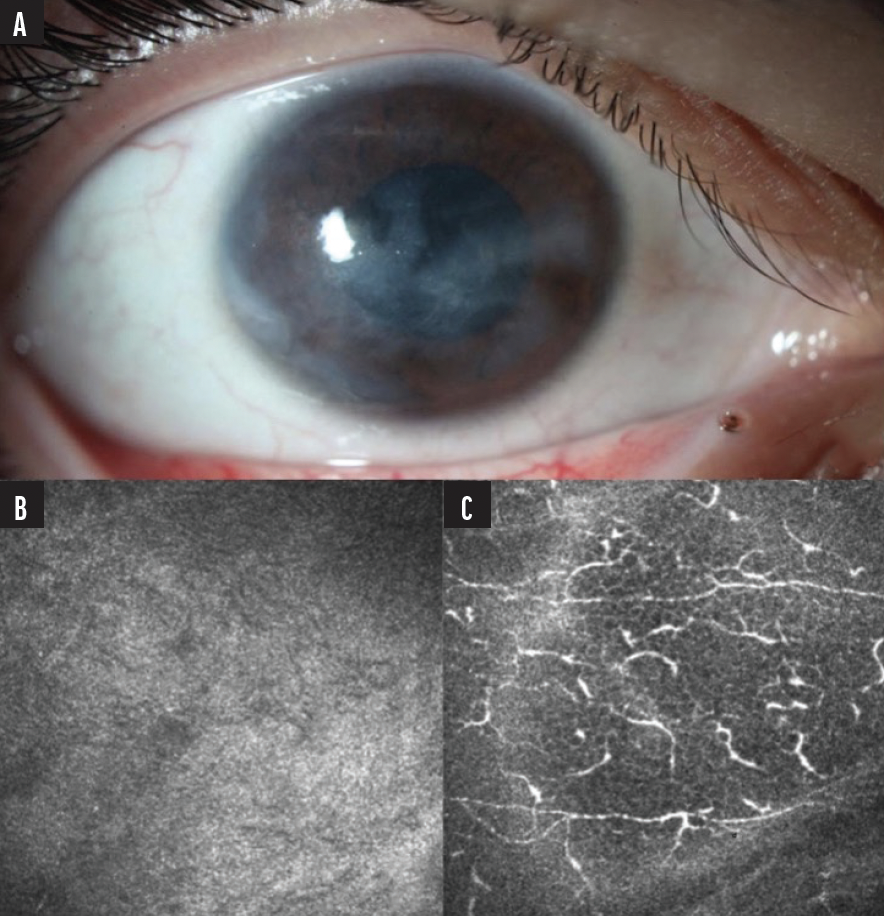

An 18-year-old woman presented to Duke’s Foster Center for Ocular Immunology for evaluation of decreased vision (fluctuating from 20/200 to hand motion), eye pain, and recurrent corneal erosions. Her past medical history included a diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome initially affecting the right lower extremity with progressive spread to bilateral upper extremities and the right side of the face. At the time of the visit, she was using three medications: gabapentin, amitriptyline, and oxcarbazepine. Ophthalmic examination revealed whirl-like epitheliopathy and corneal haze (Figure 1A). Because we suspected NK, Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometry was performed, which showed severely compromised corneal sensitivity. Based on the findings, the patient was diagnosed with very late Stage 1 NK, presumably secondary to her complex regional pain syndrome. She had not yet developed a non-healing epithelial defect or thinning. A confocal microscopy image displaying rarefaction of the corneal nerves at the epithelial subbasal plexus level helped confirm the diagnosis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. A slit-lamp photo showed diffuse epithelial irregularity and subepithelial haze (A) and rarefaction of corneal nerves at the epithelial subbasal plexus level on confocal microscopy (B). For comparison, a normal density of nerves at the subbasal plexus level in the contralateral eye is also shown (C).

Treatment and Follow-Up

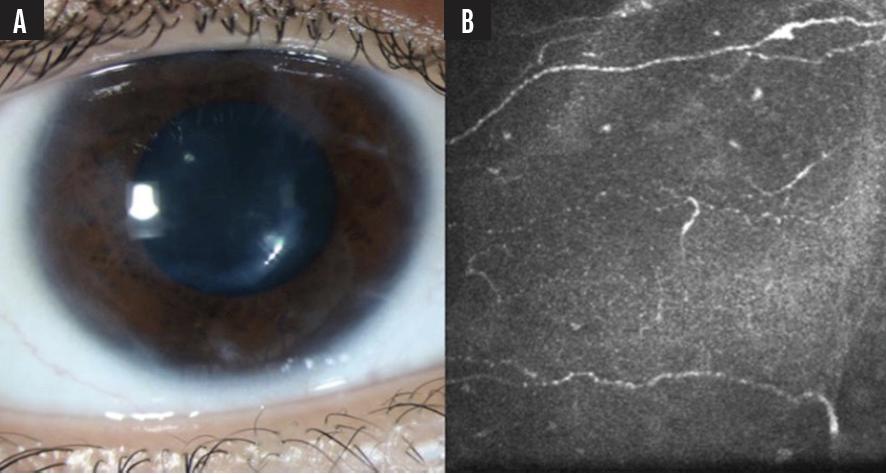

The patient was treated with superficial keratectomy, amniotic membrane graft, bandage contact lens, and plasma rich growth factor tears, and was started on an 8-week course of (cenegermin-bkbj) ophthalmic solution 0.002% (Oxervate; Dompé Farmaceutici SpA, Milan, Italy). Eleven months after treatment, the patient had improved visual acuity (20/25), resolution of ocular symptoms, increased corneal sensation to 30 mm, and showed no recurrence of neurotrophic manifestations or neuropathic facial symptoms (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Eleven months after treatment, photos showed an improved corneal surface with only peripheral scarring (A) and significant regrowth of corneal nerves at the subbasal plexus level on confocal microscopy (B).

Discussion

NK is a disease that receives little attention. With effective treatments now available, and more around the corner, earlier diagnosis and prompt initiation of treatment offers the potential to save these patients from vision-threatening complications. In a busy clinical practice, it is easy to get caught up in examining the eye and skipping over the patient’s history. Especially in instances where epithelial defects are present and impairment of corneal nerves is suspected, it is important to go back and ask questions that might unearth NK, such as:

- “Is there any known history of herpes simplex virus in the eye, or fever blisters, cold sores, or shingles?”

- “Have you been using eye drops for glaucoma or other eye issues for a long time?”

- “How long have you had dry eyes?”

- “Do you have any history of eye surgery, eye trauma, or chemical injury?”

In this case, NK was not a known complication of complex regional pain syndrome; however, a literature search revealed this disease is a poorly understood condition thought to affect the nerves. Our corneal findings, in addition to the known diagnosis, raised our index of suspicion for NK.

Testing for corneal sensation prior to administering anesthetic drops is key in diagnosing NK, which can be done with a Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometer or even the loosened tip of a cotton swab. Other features may include fluorescein staining (especially significant stain without pain), whirled epithelium (which can be accompanied by subepithelial haze), non-healing defects, and corneal thinning in more severe disease. Confocal microscopy is not a widely available tool in ophthalmology, and its use is not essential in diagnosing NK. Nevertheless, my colleagues and I have found that imaging from confocal microscopy is supportive in confirming a diagnosis.

Treatment options for NK have expanded with the availability of growth factor agents. The fundamental goal of NK management is to promote corneal healing and avoid complications. In our clinic, we are quick to prescribe cenegermin 0.002%, which contains recombinant human nerve growth factor. In clinical trials, topical cenegermin treatment resulted in increased healing compared to vehicle in eyes with Stage 2 or later NK.4,5 A more recent clinical trial is seeking to understand if there is a role for cenegermin treatment for Stage 1 NK (NCT04485546).

Newer treatment options are improving the visual prognosis for eyes with NK. However, concomitant medical conditions, especially those that may contribute to the impairment of corneal innervation, must be closely monitored. This patient’s complex regional pain syndrome has followed a progressive course. NK surfaces can decompensate quickly with minimal or no pain sensation. And so, I have recommended the patient return for follow-up every 6 months for reevaluation. In the interim, the patient is willing and able to use a scleral contact lens, which is key in this specific situation, and she continues to use plasma-rich growth factor tears. Based on the status of the cornea, treatment with the recombinant human nerve growth factor-containing agent may be repeated.

1. Semeraro F, Forbice E, Romano V, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Ophthalmologica. 2014;231(4):191-197.

2. Feroze KB, Patel BC. Neurotrophic keratitis. 2021 Nov 2. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 28613758.

3. Mackie IA. Neuroparalytic keratitis. In: Fraunfelder F, Roy FH, Meyer SM, eds. Current Ocular Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1995:452-454.

4. Bonini S, Lambiase A, Rama P, et al. Phase II randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled trial of recombinant human nerve growth factor for neurotrophic keratitis. Ophthalmol. 2018;125(9):1332-433.

5. Pflugfelder SC, Massaro-Giordano M, Perez VL, et al. Topical recombinant human nerve growth factor (cenegermin) for neurotrophic keratopathy: a multicenter randomized vehicle-controlled pivotal trial. Ophthalmol. 2020;127(1):14-16.