This 82-year-old man has a history of severe ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Despite systemic immunosuppression, his right eye worsened and ultimately underwent evisceration owing to corneal perforation and choroidal hemorrhage.

After 5 years of quiescence, the ocular surface of the left eye began to decompensate secondary to limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). Attempts to rehabilitate the cornea with tarsorrhaphies failed, as nonhealing epithelial defects and corneal ulcers recurred each time the lids were opened. Visual acuity had declined to light perception with significant functional and cognitive impairment in this previously high-functioning patient.

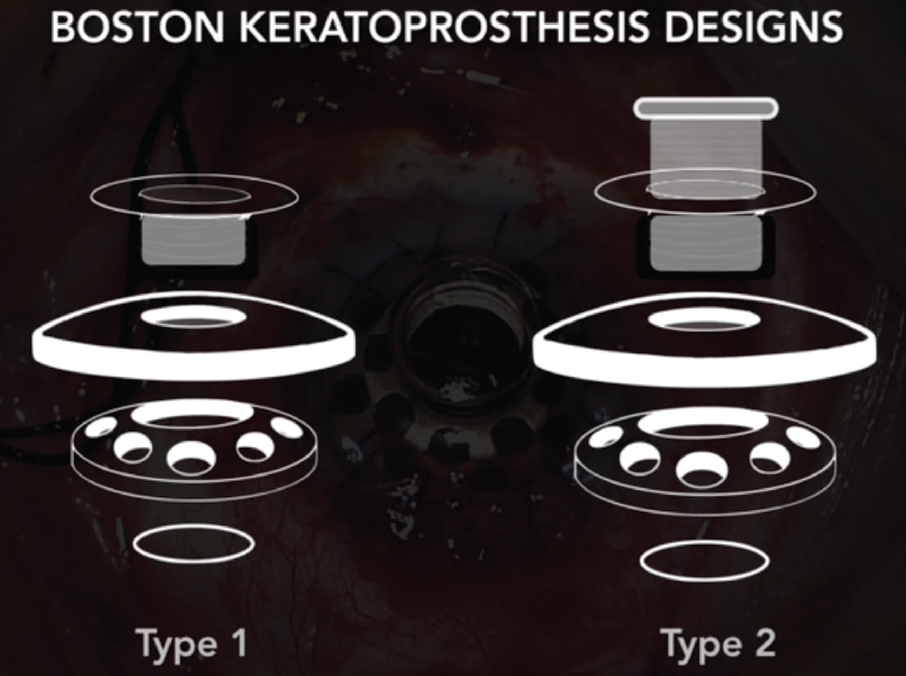

Considering the patient’s LSCD and ocular surface dryness from the underlying disease, a penetrating keratoplasty or Boston Type 1 keratoprosthesis (KPro) were deemed not likely to succeed. The decision was made to implant a Boston Type 2 KPro (Figure 1, right) as a combined case with our retina and oculoplastic colleagues for the vitrectomy and complete tarsorrhaphy.

Figure 1. Schematic of the Boston Type 1 vs. Type 2 Keratoprosthesis. Note the elongated optical cylinder in the Type 2 design that traverses the tarsorrhaphy.

The Surgery

Prior to surgery, the patient had a complete tarsorrhaphy in the left eye to protect the ocular surface. After opening the tarsorrhaphy on the day of surgery, we performed a 360° peritomy with removal of pannus tissue, followed by trephination and removal of the opacified cornea. An iridectomy was performed to expand the iris for subsequent open-sky cataract extraction, and a temporary KPro was sutured in place.

The retina surgeon then performed a vitrectomy, including removal of the capsular bag. The temporary KPro was replaced with the Type 2 Boston KPro using a flieringa ring for scleral wall stabilization and fluorescein to ensure a tight seal.

The oculoplastic surgeon then performed a full tarsorrhaphy, first excising all conjunctival mucosal tissue for proper healing. Because device extrusion is a major postoperative concern, botulinum neurotoxin was injected to paralyze the rectus muscles, thereby avoiding movements that can lead to extrusion. Finally, the eyelids were sutured fully closed over the optical cylinder.

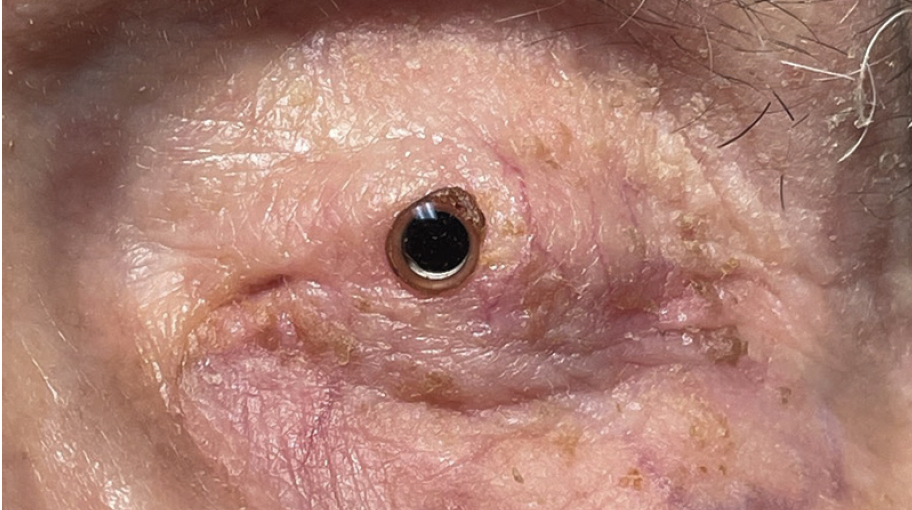

At the 6-week postoperative visit, the patient was returned to the OR, and the oculoplastic surgeon fashioned the periocular skin opening for the optical cylinder to protrude. At 4 months postoperatively, the skin around the cylinder had healed well with no extrusion or skin retraction (Figure 2). The patient’s visual acuity had improved from light perception to J2 (20/30) at near in the left eye. Nine months after surgery, the patient continues to do well, with stable vision and a return to functional activities.

Figure 2. Postoperative month 4 with the Boston Type 2 Keratoprosthesis demonstrating good device retention and no retroprosthetic membrane.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis and prompt control of inflammation are critical for the proper management of OCP/mucous membrane pemphigoid. In general, the Boston Type 2 keratoprosthesis can be considered for patients with severe, end-stage ocular surface disease where penetrating keratoplasty and the Type 1 KPro have poor prognoses. While good visual improvement is possible with KPros, long-term outcomes are tenuous. Retroprosthetic membranes, device extrusion, and glaucoma continue to pose major challenges postoperatively.

One of the keys to success in improving retention is careful attention to lid closure at the time of KPro placement. Employing a complete tarsorrhaphy with full lid closure for 6 weeks postoperatively before creating the optical cylinder window can be considered. Along with careful and continuous postoperative monitoring, we have been able to successfully restore sight to this monocular patient.