CASE PRESENTATION

A 46-year-old man presents for a refractive surgery consultation. The patient’s manifest refraction is +4.75 -6.00 x 177º = 1.33 OD and +5.00 -6.50 x 17º = 1.33 OS. An examination of the anterior and posterior segments finds a clear cornea and lens, a healthy optic nerve, and a normal retina. His history is unremarkable—no ocular surgery or disease.

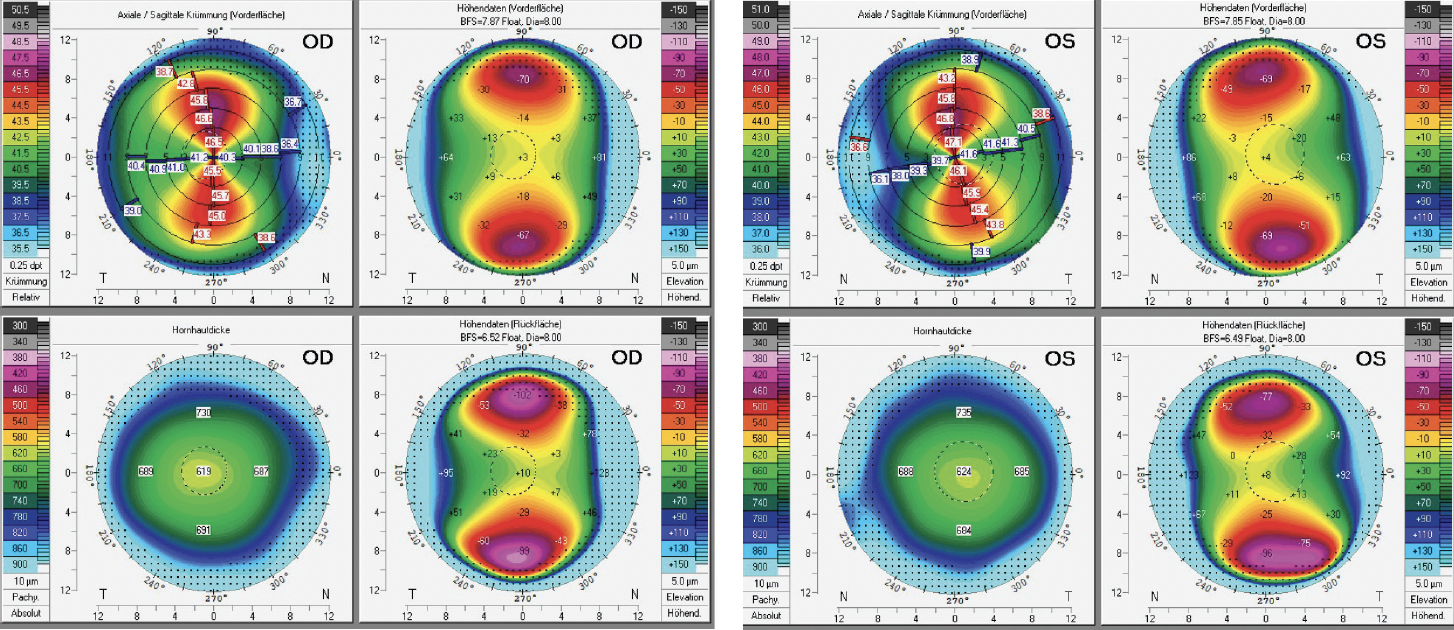

Imaging with the Pentacam AXL (Oculus Optikgeräte; Figure 1) shows regular corneal anterior astigmatism: 5.30 D OD and 5.90 D OS. The total corneal refractive power within the central 3-mm zone is 3.70 D OD and 3.90 D OS. The patient’s accommodative capacity allows him not to rely on any reading aids.

Figure 1. Scheimpflug tomography with the Pentacam AXL shows extreme but regular corneal astigmatism.

How would you proceed?

—Case prepared by Suphi Taneri, MD, FEBO-CR

ANDREW D. BARFELL, MD, AND ROBERT H. OSHER, MD

Given the patient’s age and manifest refraction, he is unlikely to function without reading glasses for much longer. The ideal refractive procedure would therefore address not only his high astigmatism but also his imminent presbyopia. In our opinion, a refractive lens exchange (RLE) with implantation of a diffractive multifocal IOL would provide him with the greatest degree of spectacle independence at distance and near. Dr. Osher called this procedure hyperopic clear lensectomy when he first presented it in the early 1980s.1,2 Several diffractive multifocal IOLs are available in the United States, where we practice, but none could completely offset this patient’s astigmatism on its own.

Dr. Osher would obtain multiple keratometry (K) readings—manually and with the IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss Meditec), Lenstar (Haag-Streit), Atlas 9000 Corneal Topography System (Carl Zeiss Meditec), iTrace (Tracey Technologies), and Pentacam—to measure the anterior and posterior corneal astigmatism. During surgery, he would use iris fingerprinting and the Callisto Eye system (Carl Zeiss Meditec) to identify the target meridian. An astigmatic keratotomy with paired corneal relaxing incisions would then be performed—a technique he described 40 years ago.3-5

Preoperatively, Dr. Barfell would counsel the patient that a sequential LASIK or PRK enhancement will likely be necessary to address his residual refractive error (a bioptics approach). In cases of planned bioptics, Dr. Barfell performs the enhancement only when refractive stability has been achieved, typically 4 to 6 weeks after IOL implantation.

Within our group at the Cincinnati Eye Institute, individual approaches may differ, but a careful preoperative assessment, counseling to set realistic expectations, and meticulous surgery would give this patient the best chance of obtaining an excellent refractive result.

SHERAZ M. DAYA, MD, FACS, FACP, FRCS(ED), FRCOPHTH

The patient has a moderate magnitude of mixed astigmatism. The corneas are thick, with normal average K readings. One option for correction would be to implant an EVO or Visian ICL (both from STAAR Surgical) if the anterior chamber depth (ACD) is sufficient and the endothelial cell count is adequate. Because the patient has spherical equivalents in the hyperopic range, however, laser peripheral iridotomies would likely be required.

Provided the ocular surface of each eye is healthy (ie, normal noninvasive tear breakup time and Schirmer test score with anesthesia), my preference would be to perform LASIK with the Technolas Teneo 317 Model 2 (Bausch + Lomb). Treatment would be delivered in a bitoric fashion, meaning the cylinder correction would be divided proportionally in myopic and hyperopic modes to correct the patient’s overall spherical equivalent. I have used this treatment approach on many patients who had a similar level of astigmatism and achieved excellent and predictable results.

ERIKA N. ESKINA, MD

Unfortunately, data from the IOLMaster and other examinations are not provided that would indicate the ACD, axial length, and size of the cornea. I therefore would not consider the option of phakic IOL implantation, although because the patient has sufficient accommodation, it would be a possible temporary solution that would allow full correction of the existing ametropia and presbyopia (implantable phakic contact lens) without changing the optical properties of the cornea.

I also would not consider laser vision correction because the manifest refraction data lead me to suspect that a greater degree of hyperopia is present than was detected with a small pupil.

The presence or absence of a posterior vitreous detachment is not stated. This would be important for deciding whether to perform an RLE.

Given the patient’s degree of hyperopia, high astigmatism (1.30 D of which is lenticular and the rest corneal), and age, my preference would be to perform an RLE with implantation of an extended depth of focus toric IOL. For example, the Tecnis Symfony Toric IOL (Johnson & Johnson Vision) is available in cylinder powers of up to -6.00 D. To preserve his near visual acuity, residual myopia (-0.50 to -0.75 D if tolerated) would be targeted in the nondominant eye.

If the patient’s lifestyle demands excellent near vision, a multifocal IOL and, if necessary, a bioptics strategy to correct his residual astigmatism could be considered. The Clareon PanOptix Toric IOL (Alcon), for example, can correct up to -3.75 D of cylinder.

JESPER HJORTDAL, MD, PHD, DMSC

RLE with a toric IOL and the implantation of a toric ICL are both options. The amount of astigmatic correction the patient requires may be beyond the range of a femtosecond LASIK procedure, but a small degree of residual astigmatism may be acceptable to him.

Intrastromal lenticule rotation, in theory, would be optimal for this patient with high regular astigmatism and low hyperopia (spherical equivalent). This recently described procedure was initially tested on human corneas ex vivo.6 It is performed as an off-label use of the VisuMax femtosecond laser (Carl Zeiss Meditec). An intrastromal lenticule that is half the dioptric power of the intended astigmatic correction is rotated 90º. Although the procedure is based on laser-assisted lenticule extraction, the lenticule is not extracted, and no donor tissue or synthetic material is added. Intrastromal lenticule rotation was evaluated clinically in a small case series.7 The results were encouraging but also found that the procedure was associated with a small myopic shift in refraction, which would be ideal in this case.

Without a doubt, complications associated with intrastromal lenticule rotation will be identified, as they are with all surgical procedures. Patients’ quality of vision and the long-term stability of refractive correction must be studied before intrastromal lenticule rotation can be widely recommended for patients with large amounts of mixed astigmatism, low hyperopia, and good BSCVA.

A. JOHN KANELLOPOULOS, MD

The Scheimpflug tomography maps show regular astigmatism in both eyes. The anterior and posterior elevation maps are normal and correspond with the sagittal curvature maps. The corneal pachymetry maps show corneal thickness to be greater than the average.

My decision on management depends on the ACD. The spherical equivalent is hyperopic, and the mean K reading is around 43.00 D. If the ACD is greater than 2 mm and the angle is wider than 10º, my first choice would be to perform topography-guided or ray tracing–optimized LASIK, which is the optimal strategy for accurate cylinder correction, especially with the topography-modified refraction strategy.8

If the ACD is less than 2 mm, however, and/or the peripheral angle narrower than 10º, then a toric IOL procedure could solve two issues. First, it would deepen the anterior chamber, countering or preventing the morbidity that the current shallowness could lead to in the intermediate or distant future. Second, a toric IOL procedure could optimize the patient’s visual function. A plano refraction and +0.50 D of with-the-rule astigmatism would be targeted in the dominant right eye. In the left eye, the aim would be a refraction of -0.75 D and +0.50 D of with-the-rule astigmatism. In our experience, this strategy usually gives patients better than 20/20 uncorrected distance visual acuity, at least J3 uncorrected near visual acuity, uncompromised contrast sensitivity at all spatial frequencies, and minimal optical aberrations.

WHAT I DID: SUPHI TANERI, MD, FEBO-CR

Normal femtosecond LASIK correction—even partial correction—seemed insufficient to meet the patient’s needs because of his extreme ametropia. I decided that an RLE could be a backup option but not a primary strategy, because the high toric power required would demand absolutely precise and stable orientation of the IOL inside the capsular bag. Furthermore, parallax error was likely to reduce his quality of vision.

Instead, lenticule rotation was implemented.6,7 A corneal flap and toric stromal lenticule were created with the SMILE software on the VisuMax 500. The lenticule had a toric power equal to only half of the manifest refractive cylinder. The flap was lifted, the lenticule was rotated 90º, and then the flap was repositioned. A spherical refraction was targeted.

Eight months after surgery, the patient’s UCVA was 1.0 OD and 0.8 OS, and both the lenticule and cornea were clear (Figure 2). His manifest refraction was +0.50 -0.50 x 21º OD and +1.00 -1.00 x 46º OS.

Figure 2. Slit-lamp photograph taken 8 months after rotation of an intrastromal lenticule under a flap. The cornea is clear.

A flap was created because my original plan was to ablate the lenticule with an excimer laser. The patient was so satisfied with his outcome, however, that he did not want further refinement. If he undergoes an RLE or cataract surgery in the future, either procedure will be aided by a residual total corneal refractive power of 0.70 D OD and 0.80 D OS.

1. Osher RH. Clear lens extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1994;20(6):674.

2. Osher RH. Clear lensectomy. In: Fine IH, ed. Clear Corneal Lens Surgery. Slack; 1999:281-285.

3. Osher RH. Iris fingerprinting: new method for improving accuracy in toric lens orientation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36(2):351-352.

4. Osher RH. Paired transverse relaxing keratotomy: a combined technique for reducing astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1989;15(1):32-37.

5. Osher RH. Contemporary refractive surgery: transverse astigmatic keratotomy combined with cataract surgery. In: Stamper RL, Thompson KP, Waring GO III, eds. Ophthalmology Clinics of North America. Vol. 5. W.B. Saunders; 1992:717-725.

6. Damgaard IB, Ivarsen A, Hjortdal J. Intrastromal lenticule rotation for treatment of astigmatism up to 10.00 diopters ex vivo in human corneas. J Refract Surg. 2019;35(7):451-458.

7. Stodulka P, Hjortdal J, Slovak M. Intrastromal lenticule rotation for the treatment of high astigmatism. J Refract Surg. 2020;36(6):415-418.

8. Kanellopoulos AJ. Topography-modified refraction (TMR): adjustment of treated cylinder amount and axis to the topography versus standard clinical refraction in myopic topography-guided LASIK. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:2213-2221.