CASE PRESENTATION

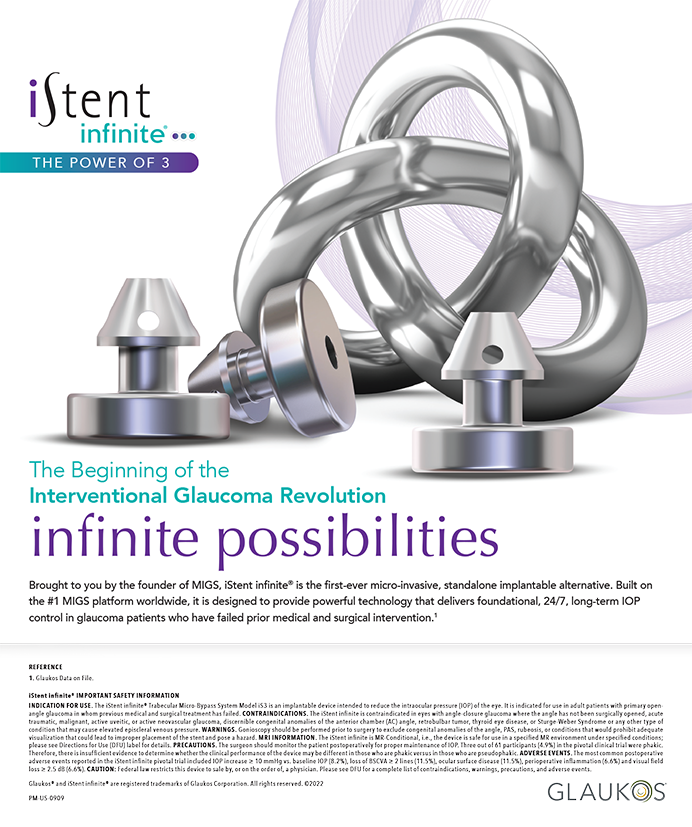

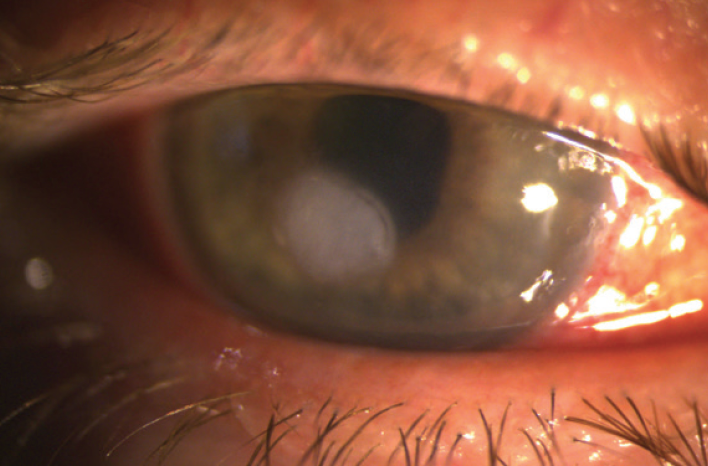

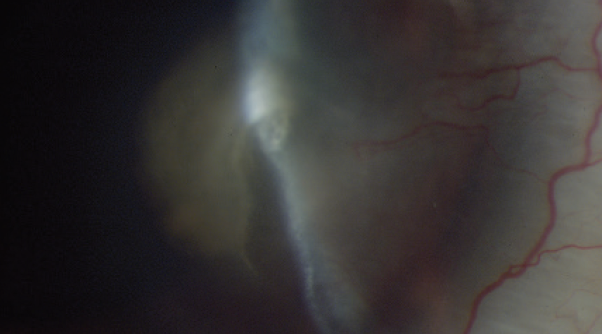

A 50-year-old woman presented with a 3 x 3-mm paracentral epithelial defect, a stromal infiltrate, and edema involving the LASIK flap in her right eye (Figure 1). The patient had undergone LASIK and enhancement procedures in each eye several years ago. She had been treated in the past for recurrent corneal erosions, and she had received punctal plugs for ocular surface dryness. She reported that the current corneal erosion had developed 3 days earlier. Her medical history was significant for controlled type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1. Paracentral ulceration involving the LASIK flap.

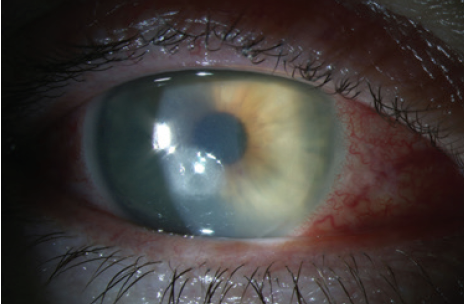

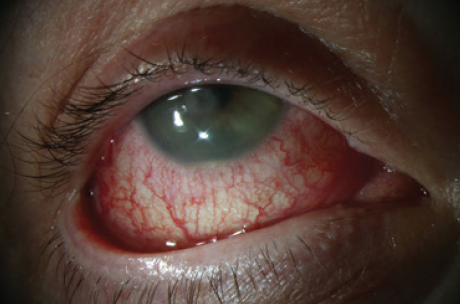

An examination found a 1-mm hypopyon (Figure 2) and very fine, finger-like projections in the stroma (Figure 3). Suspecting an infection, I cultured the eye and initiated therapy with ofloxacin ophthalmic solution 0.3% (Ocuflox, Allergan) administered six times daily and cycloplegia. Although I used a Kimura spatula for the culture, the texture of the stroma was extremely dry, providing inadequate material for a Gram stain.

Figure 2. A 1-mm hypopyon evident on initial presentation.

Figure 3. Feathery finger-like projections at the edge of the infiltrate.

Continuity of care was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Another physician saw the patient 4 days later and concluded that her condition was worsening. The eye was recultured, and a swab was sent for herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction. Both sets of cultures were negative.

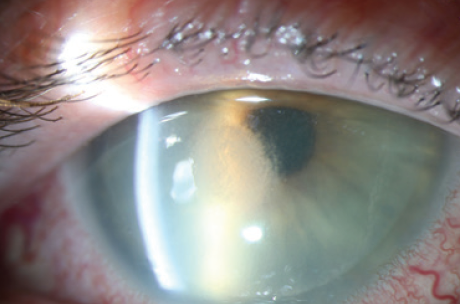

Six days later, the ulceration had deepened with accompanying inflammation, and erosion through the LASIK flap was evident (Figure 4). Confocal microscopy was not available on that day. Given the severity of the situation and the lack of a definitive diagnosis, I recommended and performed flap amputation. All cultures remained negative, and histochemical pathology stains were negative for bacteria, fungi, amoeba, and viral inclusions.

Figure 4. Progression of the infiltrate and ulceration through the LASIK flap.

Steroid therapy was increased, leading to a notable improvement. A review of systems was completely negative for autoimmune and systemic inflammatory diseases. The patient has a pronounced nickel allergy and mild cutaneous rosacea. I concluded that she had experienced a noninfectious inflammatory flap melt secondary to ocular rosacea. Her condition continued to improve with a regimen of topical steroids and oral doxycycline. Reviewing her past outside records suggested that her previous episodes of red eye were likely bouts of ocular rosacea rather than recurrent erosions. Topography performed 4 weeks after the flap amputation (Figure 5) showed ongoing healing. Seven weeks after amputation, stromal scarring was clearing (Figure 6).

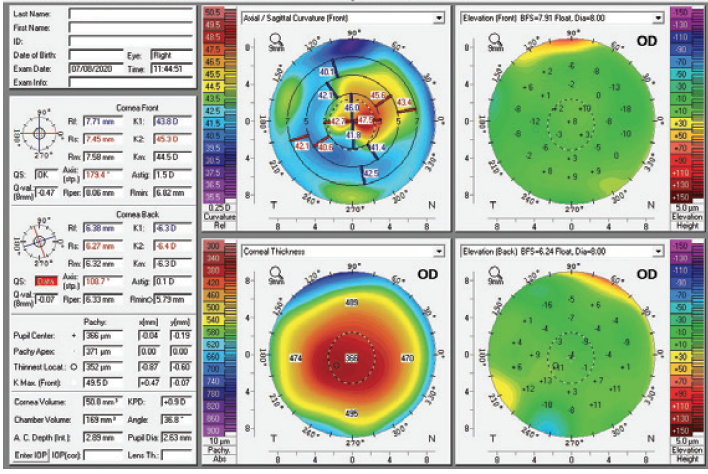

Figure 5. Topography 4 weeks after LASIK flap amputation.

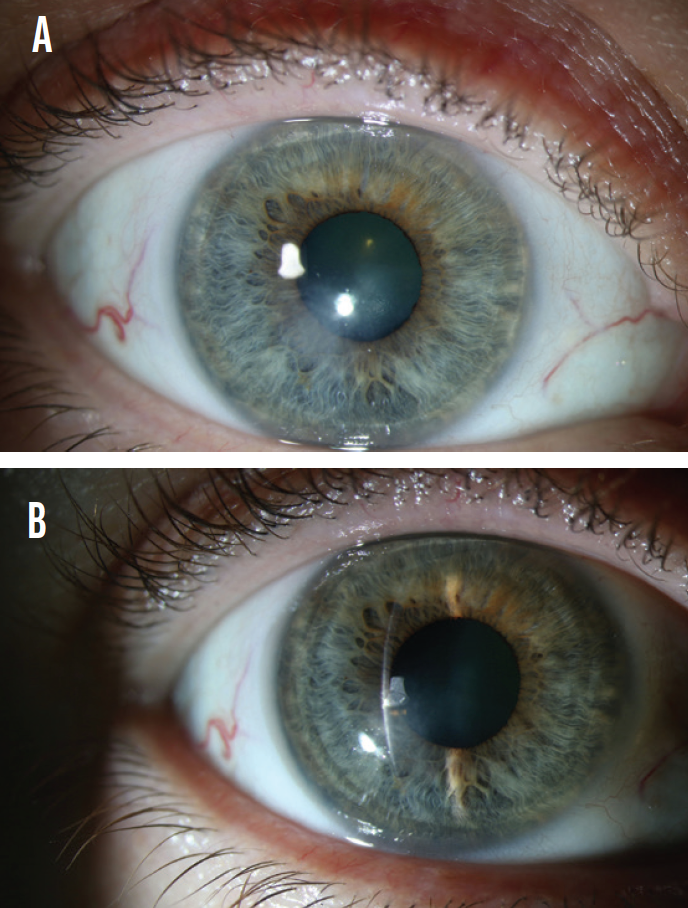

Figure 6. Healing with reduced scarring 7 weeks after flap amputation (A). Healing with scarring limited to the anterior stromal bed 7 weeks after flap amputation (B).

How often do you see ocular rosacea out of proportion to a patient’s cutaneous rosacea? What is the relationship between ocular rosacea and a nickel allergy? In North Carolina, changes in season are accompanied by significant changes in temperature. Could these activate rosacea? Apart from advanced epithelial downgrowth, have you seen other noninfectious causes for a LASIK flap melt? How would you manage this patient in the long term with respect to her recovering vision and her rosacea?

—Case prepared by Alan N. Carlson, MD

NATALIE AFSHARI, MD, FACS

A well-known history of rosacea can have a relationship with nickel allergy. In a study of 40 patients with rosacea, there was an association between nickel sensitivity and rosacea. This can be because nickel may be one of the underlying pathologies or one of the triggering factors of rosacea.1

Ocular rosacea can be out of proportion to a patient’s skin rosacea.2 Given that rosacea involves vessels and telangiectasia, it may fluctuate with environmental heat.3 I typically see flap melt from infections, less commonly these days from epithelial ingrowth.

It is unusual that this patient did not have any infection. If a persistent epithelial defect develops in the future, after a negative culture, I would consider prescribing serum tears and nerve growth factor treatment.

ERNEST J. OTERO, MD

This is a challenging case on diagnostic and therapeutic levels. The patient presented with a central corneal infiltrate, an ulceration, associated flap edema, and, evident in Figures 1 and 2, diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) and hypopyon. The negative cultures notwithstanding, these findings suggest an infectious (bacterial) nature and, most likely, gram-positive bacteria. A corneal ulceration probably became infected. I would have prescribed a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone initially as opposed to ofloxacin. Although both generations of antibiotic have similar spectrums of action against gram-negative bacteria, fourth-generation fluoroquinolones are more effective against gram-positive and atypical bacteria. I believe the feathery edges of the infiltrate are related to DLK.

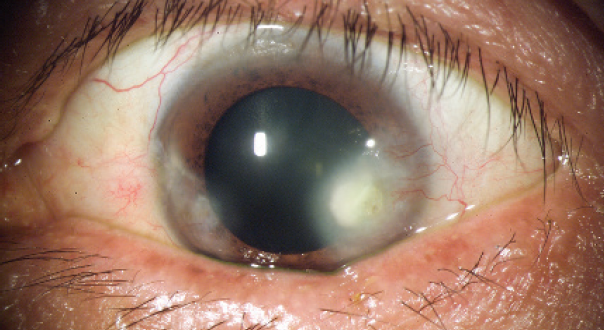

Rosacea is a known cause of evaporative dry eye disease and severe ocular surface disease. Although the presentation in this case is atypical of ocular rosacea, the erosion and the ulceration that led to the secondary bacterial infection and corneal melt might have been elicited by dryness associated with rosacea. In my corneal referral practice, I frequently encounter patients with ocular rosacea. The presentation is characterized by dense peripheral (near the limbus) intrastomal corneal infiltrates associated with stromal vascularization (Figures 8 and 9). Rosacea presents as an interstitial keratitis. Exacerbation of rosacea by hot and cold environments has been documented, as has aggravation from alcohol consumption, stress, the ingestion of hot or spicy foods, and sun exposure.4

Figure 8. Typical interstitial keratitis in a patient with rosacea.

Figure 9. Corneal ulceration in a patient with rosacea.

Figures 8 and 9 courtesy of Ernest J. Otero, MD

Although rare, noninfectious causes of corneal melt include drug toxicity (ie, proparacaine eye drops, diclofenac eye drops), stage 4 DLK, and decreased corneal sensitivity.

Long-term management can be challenging in this situation. Flap amputation causes a hyperopic shift. The patient has a residual corneal scar (haze) produced by the keratitis. Irregular astigmatism is evident on corneal Scheimpflug tomography, with up to 5.00 D of difference between the steepest and flattest points in the central cornea. Steroid therapy (loteprednol) should be continued until the cornea clears, after which the drug may be tapered. OCT of the cornea should be performed to assess the true thickness and depth of the residual leukoma.

A contact lens fitting (preferably a soft lens) may be scheduled if the patient’s visual acuity is good enough. If vision is poor, a scleral contact lens is an option. If visual acuity is poor and the scar is deep (not how it appears in the figures), a deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty may be considered. If scarring is superficial, a femtosecond laser–assisted anterior lamellar keratoplasty may be preferable because the visual recovery tends to be faster than after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty or penetrating keratoplasty.5

What i did: ALAN N. CARLSON, MD

Acute inflammation involving the cornea raises the question: Is this an infection? This is answered by addressing the following questions:

- Is the epithelium intact?

- What is the stromal response (infiltrative or suppurative necrosis)?

- What is the location relative to the limbus, and is the lesion singular or multifocal?

- Is there discharge such as tearing, mucous, or mucopurulent discharge?

- Is there anterior chamber inflammation or hypopyon?

By every criterion, this patient qualified for a culture and Gram stain and for treatment as though she were infected. Despite repeatedly negative cultures, her condition continued to worsen on treatment, which led to therapeutic amputation of the LASIK flap. Pathology was notable for inflammation without infection, and her condition began to improve on steroids.

Spontaneous, noninfectious keratitis raises the issue of autoimmune diseases or, in this case, the patient’s rosacea and pronounced nickel allergy. One of the lesser-known triggers of rosacea, a change in temperature, may be why I see so many cases in North Carolina, where it is not uncommon for the temperature to vary by as much as 50 ºF within a single week. If a patient with chronic red eye has seen multiple other physicians and has not responded to antiinfectious regimens, I recommend ruling out the following conditions: rosacea/meibomian gland dysfunction, floppy eyelid syndrome, superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis of Theodore, mucus fishing syndrome, molluscum contagiosum, medicamentosa, and anesthetic abuse.

Rosacea, particularly ocular rosacea, is often a missed or delayed diagnosis, and it continues to challenge clinicians’ understanding in terms of basic pathogenesis.

1. Çifci N. Nickel sensitivity in rosacea patients: a prospective case control study. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2019;19(3):367-372.

2. Browning DJ, Proia AD. Ocular rosacea. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986;31(3):145-158.

3. Gonzalez-Cantero, Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, et al. Do dermatologic diagnosis change in hot vs. cold periods of the year? A sub-analysis of the DIADERM National Sample (Spain 2016). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110(9):734-743.

4. Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2018:338.

5. Shetty R, Nagaraja H, Veluri H, et al. Sutureless femtosecond anterior lamellar keratoplasty: a 1-year follow-up study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(9):923-926.