CASE PRESENTATION

A 68-year-old woman is referred by her retina surgeon for a cataract evaluation in the left eye, which underwent retinal surgery several weeks ago. The patient says her vision never fully returned after the procedure, and she reports progressive worsening and the development of a green tint.

On examination, her UCVA is 20/25 OD and 20/200 OS. Her BCVA is 20/20 OD with minimal correction and 20/80 with a manifest refraction of -5.15 +1.50 x 160º OS. Motility is full, and no afferent pupillary defect is evident. A slit-lamp examination of the right eye is essentially normal aside from a mild cataract. The left eye has a quiet conjunctiva and anterior chamber, a clear cornea, and a normal iris with a very small transillumination defect. The crystalline lens exhibits significant nuclear changes and an unusual green tint (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An examination of the left eye reveals a green tint to the lens. The nasal iris defect is difficult to see.

The results of a posterior examination of the right eye are normal, but the left eye has a visually significant epiretinal membrane (ERM). Additional test results and measurements are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Topography of the left eye shows against-the-rule astigmatism.

Figure 3. Biometry of the left eye.

How would you approach the cataract in the patient’s left eye?

— Case prepared by Brandon D. Ayres, MD

ZACHARY LANDIS, MD

The presentation raises concern about an inadvertent injection of indocyanine green (ICG) into the posterior crystalline lens with likely posterior capsular rupture (PCR). The preoperative B-scan does not show a definite hyperechoic signal posterior to the lens, so ICG could be present in the retrolenticular space if the anterior hyaloid membrane was not removed during the prior surgery. A frank conversation with the referring surgeon is required for surgical planning. The patient would receive extensive preoperative counseling on her increased surgical risk, the possibility of a dropped nucleus, and the potential need for additional surgery.

Any abrupt changes in anterior chamber dynamics from the very first incision could cause the PCR to extend and the nucleus to drop. The case would therefore be scheduled with a trusted vitreoretinal colleague on standby.

Overfilling the anterior chamber with a dispersive OVD would be avoided at the beginning of the case, and low IOP settings would be used. Hydrodissection would be avoided in favor of hydrodelineation. The nucleus would be divided into hemispheres, which would be phacoemulsified without rotation. Next, viscodissection would be performed to loosen the epinuclear material, and the cortical material would be stripped slowly, with that closest to the PCR addressed last. The chamber would be formed with a dispersive OVD before instruments are removed from the main incision.

A three-piece acrylic IOL would be placed in the sulcus with optic capture. Alternatively, another surgeon who is comfortable with a posterior capsulorhexis and the preexisting PCR could consider implanting a one-piece acrylic IOL in the capsular bag.

BRYAN S. LEE, MD, JD

Given the rapid onset of the cataract and the intralenticular dye, I assume a preexisting capsular defect is present.

I would prepare the patient for the risks of complicated surgery and possible need for a third surgery and/or another IOL procedure later in life. I would explain that the surgical plan might change intraoperatively and let her know in advance that she might experience metamorphopsias postoperatively and that her visual potential is unknown.

I would offer astigmatism correction but not a multifocal IOL. Moreover, I would hesitate to implant an extended depth of focus IOL given the ERM and uncertainty whether a one-piece acrylic IOL can be implanted. Because the axial length is short and the keratometry readings are steep, the IOL calculation might be imprecise. Because of the presumed capsular defect, extra OR time would be scheduled, and the OR staff would be instructed to prepare accordingly.

I would make a capsulorhexis on the small side to allow optic capture. If the capsule has a defect, it might be difficult to place the haptics of a one-piece acrylic lens in the bag with reverse optic capture because the transillumination defect is located in the nasal quadrant, where a haptic would have to go. If she would like her astigmatism corrected, I would favor a Light Adjustable Lens (RxSight) because it could be placed in the sulcus with optic capture if necessary. If the patient does not want a Light Adjustable Lens and the capsule is not amenable to a toric one-piece acrylic IOL, then I would offer a limbal relaxing incision if she accepts that astigmatism correction with this approach is less accurate than with either IOL.

NANDINI VENKATESWARAN, MD

Little information on the vitrectomy is provided. The presence of a nasal iris transillumination defect makes me wonder whether an intraocular foreign body was removed. The green tint to the crystalline lens raises concern about extravasation of a dye such as ICG into the lens from an area of capsular compromise during the vitrectomy or the presence of an intralenticular foreign body.

First, the patient would be counseled on her increased risk of PCR, vitrectomy, and retinal detachment due to her history of retinal surgery. It would also be explained that the eye’s visual potential may be limited by the ERM.

In preparation for complexities that might arise, the OR would be equipped with a variety of surgical instruments and materials, including the following:

- Iris hooks for iris expansion in the event that the nasal transillumination defect is a harbinger of a floppy iris;

- Capsular hooks, a capsular tension ring, a capsular tension segment, and PTFE sutures (Gore-Tex, W.L. Gore & Associates) in case additional capsular support is required to address zonulopathy;

- A set of instruments from MicroSurgical Technology in the event a foreign body must be removed;

- Triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog, Bristol-Myers Squibb) and an anterior vitrector for a possible anterior vitrectomy; and

- A one-piece, a three-piece, and an anterior chamber IOL.

At the start of the case, the anterior capsule would be stained with trypan blue dye because the lens’ green hue could obscure the red reflex. Dilute triamcinolone acetonide would be injected to help determine whether vitreous is present in the anterior chamber. Any vitreous detected would be removed with the anterior vitrector.

If capsular support is inadequate during the capsulorhexis, capsular hooks would be placed. Given the possibly compromised posterior capsule, gentle hydrodissection or hydrodelineation alone would be performed. The nucleus would be disassembled with chopping techniques to reduce stress on the zonules, and lens material would be viscodissected to help create a barrier between it and the posterior capsule in case a tear is detected. In that event, a thorough anterior vitrectomy would be performed as needed. An intralenticular foreign body, if detected, would be removed.

The choice of IOL would depend on the status of the posterior capsule. Given the presence of a visually significant ERM, my preference would be either a one-piece monofocal IOL in the bag or a three-piece IOL in the sulcus with optic capture. Acetylcholine chloride intraocular solution (Miochol-E, Bausch + Lomb) would be administered to constrict the pupil at the end of the case if the posterior capsule has ruptured, and the main wound would be sutured. A subconjunctival steroid injection could be performed to reduce intraocular inflammation.

After surgery, the patient would be referred to a retina specialist for a thorough examination and a conversation on how to proceed with regard to the ERM.

WHAT I DID: BRANDON D. AYRES, MD

The examination findings were highly suspicious for a violated lens capsule. The increased risk of complications during cataract surgery after retinal surgery was discussed with the patient. To mitigate the risk of multiple trips to the OR, her retina surgeon agreed to be available during cataract surgery in case a capsular complication occurred. The retina surgeon also disclosed a suspicion of capsular violation with the cannula used to instill ICG.

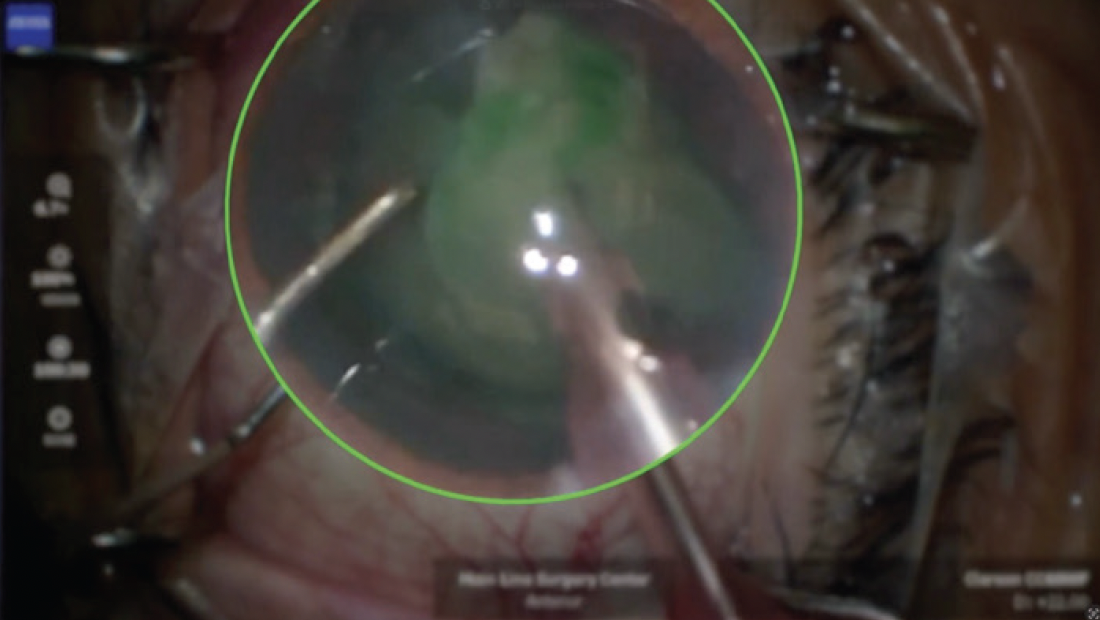

In the OR, the left eye was prepped and draped. The microscope view revealed ICG staining of the lens or lens capsule but no clear area of perforation (Figure 4). Given the high suspicion of violation, care was taken to avoid overpressurizing the eye with an OVD. The overall size of the capsulorhexis was kept small enough to capture the optic of the lens implant if sulcus fixation became necessary.

Figure 4. The appearance of the lens and red reflex at the beginning of the cataract procedure. Note the obvious green hue to the light reflex.

Hydrodelineation was performed in lieu of hydrodissection in an effort to avoid propagation of a capsular tear. The nuclear portion of the lens was removed with minimal rotation, and it became clear that ICG was present in the lens material (Figure 5). The epinuclear material was kept in place to protect the capsule. An OVD was injected every time an instrument was changed in the eye to avoid shallowing of the anterior chamber. The I/A unit was then used to remove the epinuclear material, and the capsule was left intact. Before removal of the I/A unit, the capsular bag was filled with an OVD, and the IOL was implanted in the bag.

Figure 5. ICG embedded in the lens material.

Figure 6. A suspected area of perforation of the anterior capsule with fibrosis. Luckily, the capsular perforation did not extend during cataract surgery.

The patient did well after surgery, but her UCVA was 20/60 OS with severe metamorphopsia due to macular pathology. She returned to the OR for a second ERM peel by her retina surgeon and is currently recovering. Time will tell what her final visual acuity will be.