Combatting Stress and Burnout

Cathleen M. McCabe, MD

COVID-19 has presented a tremendous challenge to the world at large and, more specifically, to physicians on the front lines, ophthalmologists, medical staff, and patients. We ophthalmologists have had to navigate the financial stress of lockdowns, interruptions in patient care, and the restructured practice of medicine to increase safety for our patients, our staff, and ourselves. Despite bright spots of innovation (eg, telehealth) and collaboration (eg, international learning through webinars), the stress of balancing the competing needs of patients, staff, physicians, administrators, and the government takes its toll. Exacerbating this stress in the United States are record numbers of hurricanes and wildfires, social unrest, and a polarizing 2020 presidential election.

BURNOUT

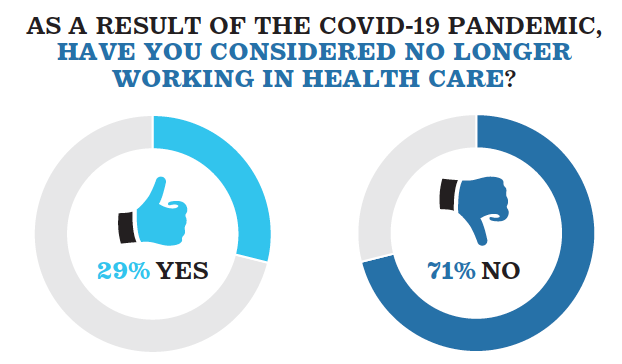

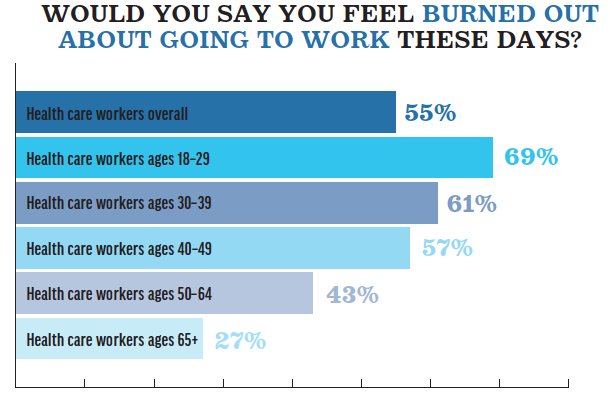

Burnout in the medical field is at an all-time high. In a recent poll of health care workers, approximately one-third reported that they had considered leaving the health care field because of the pandemic (Figure 1).1 More than half of respondents reported feeling burnout; that figure rose to 69% in the youngest group (18–29 years) of respondents (Figure 2).

Figure 1. In a recent poll conducted by The Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation, one-third of health care workers reported considering leaving health care owing to the pandemic.

Figure 2. In that same poll, younger workers were most likely to report burnout.

Source: The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation

The departure of physicians, nurses, and technicians from the field of medicine reduces an aging population’s access to health-related services. During the shutdown in 2020, many practices were forced to lay off and furlough staff in order to survive financially. Some practices pulled together to provide essential services to patients with urgent and emergent needs while maintaining barebones staffing. Even now, many practices are doing more with fewer people because of retirement, difficulty hiring staff, and a continuing need to operate more efficiently for financial reasons. All of this puts additional stress on the staff, doctors, and patients who may be reluctant to seek care out of fear about SARS-CoV-2 transmission or who are on waiting lists for treatment.

At my practice, I have observed manifestations of stress among some of my patients in the forms of more aggressive interactions with staff, decreased tolerance for change (eg, wearing masks), and an increased number of no-show appointments. Moreover, patients who have delayed health care often return with more advanced disease, making management more complex.2

Adding to the current complexity of medical practice, doctors’ perceptions of risk and reasonable steps vary, which can make it challenging to find flexibility and consensus regarding modifying schedules, wearing personal protective equipment, and changing patient flow through the practice. People in leadership positions and those in administration are trying to balance the needs of business with those of employees and patients.

My practice partnered with a private equity firm a little more than 3 years ago, and this financial backing has helped us to maintain daily operations. It is not surprising that an increasing number of individual practices are expressing interest in partnering with a larger entity such as a private equity firm3 to mitigate the risk that a future unexpected disruption in care could cause. Ophthalmology as a whole experienced the greatest decrease (29%) in Medicare billing during the first 6 months of 2020, as shown in a recent report by the American Medical Association.4 Another American Medical Association survey conducted in July and August 2020 found that 81% of physician revenue was still below prepandemic levels.5 Meanwhile, physician reimbursement has continued to trend downward; ophthalmology narrowly avoided an average 6% reduction in Medicare reimbursement this year.6

MITIGATION

How can the effects of all this stress be mitigated? Mehta and Murphy7 laid out four key initiatives to prevent burnout (outlined in Preventing Burnout). Further, national subspecialty groups, large consolidated organizations, and individual practices can help by prioritizing the health and well-being of physicians and other health care providers. Medical societies can also play an important role in this quest. Some ways these organizations can influence change include the following:

- Advocate for prioritizing changes in national and state legislation and health policy that may reduce burnout;

- Develop tools to improve practice efficiency;

- Support lifelong learning in a timely and convenient manner; and

- Facilitate a sense of community, diversity, and inclusion for their members.

PREVENTING BURNOUT

Four key initiatives

1. Acknowledge that burnout is an adverse effect of a given occupation and not the fault of the individual.

2. Develop organizational strategies to support clinicians’ well-being that extend beyond addressing personal resiliency. Efforts should shift to improving organizational culture and practice efficiency.

3. Address mental health conditions in a safe, confidential, and nonjudgemental manner.

4. Conduct research to develop guidelines and best practices for improving the culture of wellness, practice efficiency, and resiliency in health care.

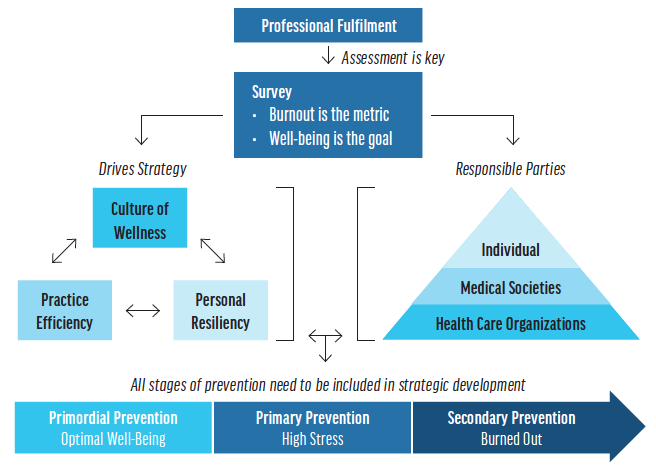

According to the Stanford Medicine WellMD & WellPhD Center,8 a holistic approach to addressing the well-being of clinicians incorporates three components to achieve professional fulfilment: a culture of wellness, practice efficiency, and personal resiliency (outlined in The Stanford WellMD Model for Increasing Clinician Well-Being). The use of surveys to develop a culture of wellness, practice efficiency, and personal resiliency is key. Health care organizations, medical societies, and individuals have unique roles in addressing well-being. All stages of prevention must be included in strategic development, from primordial prevention for those individuals with optimal levels of well-being to primary prevention among those with high levels of stress to secondary prevention among those who have experienced burnout (Figure 3).

THE STANFORD WELLMD MODEL FOR INCREASING CLINICIAN WELL-BEING

Three components to achieve professional fulfilment

A culture of wellness

- Ensure leadership supports and values self-care

- Make resources for peer support and community development available

- Fosters a culture of fairness and inclusivity

Practice efficiency

- Workplace systems promote teamwork models of practice

- Redesign inefficient systems with the input of physicians and stakeholders

- Engage efficient methods to improve work-life balance

Resiliency

- Engage individuals to promote actions that contribute to emotional, physical, and professional well-being

- Promote self-care, self-compassion, social support, and safety net programs for crisis intervention

Figure 3. A flow chart showing how survey assessment is key to professional fulfilment.

It is the responsibility of practice owners and those in leadership positions to prioritize the three areas of professional fulfilment as well as to support diversity, inclusion, and equity in ways that do not increase the burden on the doctors and staff already at risk of burnout. At first blush, it may sound helpful to create a task force on equity, diversity, and inclusion and a team to address physician wellness. If, however, the meetings, events, and education involved require additional effort and time from already stressed members, will the desired goals be achieved?

CONCLUSION

It may be tempting to return to how ophthalmology was practiced before the current pandemic, but that also comes with crowded waiting rooms, crazy schedules, and a focus on productivity but not wellness. I have a different vision for the future—one that takes into consideration the challenges and stresses that COVID-19 has presented.

Ophthalmology is more than the business of medicine. It is a community of people—doctors, staff, administrators, and patients—who must evolve to prioritize our collective wellness in order to create a better future for us all.

1. KFF and Washington Post frontline health care workers survey. The Washington Post. March 2021. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://context-cdn.washingtonpost.com/notes/prod/default/documents/4d8d1ddf-c192-40f9-9e3a-7a3fefa0d928/note/91e5f1ac-2cc5-41bb-b164-ecb4d77ed0b5.#page=1

2. Will health care infrastructure survive the COVID-19 pandemic? Justanoldcountrydoctor blog. April 14, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://justanoldcountrydoctor.com/2020/04/14/will-health-care-infrastructure-survive-the-covid-19-pandemic

3. Bibet-Kalinyak I. Private equity in 2021. CRST. March 2021. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://crstoday.com/articles/mar-2021/private-equity-in-2021/

4. Gillis K. Policy research perspectives. American Medical Association. March 2021. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-03/prp-covid-19-medicare-physician-spending.pdf

5. COVID-19 financial impact on physician practices. American Medical Association. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/sustainability/covid-19-financial-impact-physician-practices

6. AAO: Planned Medicare cuts deal heavy blow to nation’s ophthalmologists. Eyewire. August 6, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://eyewire.news/articles/aao-planned-medicare-cuts-deal-heavy-blow-to-nations-ophthalmologists/

7. Mehta LS, Murphy DJ Jr. Strategies to prevent burnout in the cardiovascular health-care workforce. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021:1-2.

8. Swenson SJ, Shanafelt TD. Mayo Clinic Strategies to Reduce Burnout: 12 Actions to Create the Ideal Workplace. Oxford UP; 2020.

Finding Balance

Priyanka Sood, MD

What a year it has been! Many of us had hoped and planned for 2020 to be the Year of Eye Care, but in the end, 2020 was a year of introspective and inventive vision. As the well-known proverb states, necessity is the mother of invention. Facing the challenges of COVID-19 forced us all to ascertain new methods for patient care with an innovative and sometimes desperate spirit. As we continue to learn what will return to normal and what has become the new normal, one thing is blatantly obvious: None of us is immune to the emotional effects of a pandemic, and mental grit does not last forever.

THE EARLY STAGES

Looking back, as word spread of our European colleagues’ plight with SARS-CoV-2, it began to sink in for those of us stateside that this ordeal was not going to last a few weeks but likely many months. I practice in an academic setting and had immediate and intimate knowledge of the massive volume of patients with COVID-19 who were receiving treatment and the number of ventilators and amount of personal protective equipment that were available on a daily basis.

As in the rest of the United States and the world, our ophthalmology practice was shut down except for emergency cases. Our patients’ ophthalmic diseases, however, progressed in spite of the lockdown. We transitioned to the provision of patient care via teleophthalmology quickly and furiously, and our technology-savvy medical students and residents were eager to assist in this quest. Teleophthalmology is far from perfect, but it afforded us the opportunity to provide some level of care to our patients.

As the novelty of invention wore off, the reality of the changes to our daily lives became more obvious. The loss of community, the unknown outlook for the future, and the social and political unrest in our country left many of us feeling drained and uncomfortable. As the news of furloughs and pay cuts swirled, it was hard to grasp the full impact of the pandemic.

OPPORTUNITY FOR GROWTH

After the lockdown lifted, our clinic and OR schedules began to pick up. Our normal downtime routines, however, were not available to us. Gyms were closed, restaurants were offering takeout only, and concerts and events were cancelled. We went from home to work and back again. Physician burnout was on the rise before the pandemic,1-3 and COVID-19 seemed to add insult to injury.

Many of us, however, have taken this time of uncertainty during the pandemic as an opportunity for personal and professional growth. As Wong suggests in her article on physician burnout, “the many pitfalls and distress that physicians encounter can be looked at as positive disintegration—the stress, anxiety, and crises that physicians face are important opportunities for growth, maturation, and transformation.”4

The challenges of feeling moral injury or burnout can therefore empower us to advocate for ourselves and ultimately our patients. We are more effective and efficient when we are in a state of optimal health. Suffering in silence is not the answer, nor is putting the onus on physicians to treat themselves. For me, the time I have had during the pandemic to reflect and reenergize has been impactful. I began to focus on my physical health (hello, COVID-13 pounds), and I realized that my emotional and social health were in need of attention as well. Finding balance therefore became a priority for me during this past year, and I have chosen to focus on achieving optimal health (see Five Key Areas of Health).

FIVE KEY AREAS OF HEALTH

Optimal health has been described as a balance of five key areas of health.1

- Emotional. This refers to our state of mind and feelings and involves coping with stressful situations, frustration, disappointment, and excitement.

- Physical. This area of health encompasses fitness, nutrition, and the control or abstinence of chemical abuse.

- Spiritual. A belief or faith in something greater or in understanding and fulfilling one’s purpose in life constitutes spiritual health.

- Intellectual. Physicians excel at intellectual health, which includes the ability to set and achieve career, educational, and financial goals.

- Social. Cultivating stable relationships with friends, family members, peers, and coworkers and having a sense of confidence and security within ourselves falls under social health.

1. O’Donnell MP. Definition of health and promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1986;1(1):4-5.

BATTLING BURNOUT

The six most common causes of burnout include workload, perceived lack of control, reward, community, fairness, and values mismatch. Some of these areas played a key role in inducing burnout in our work lives at various points in the past year.

Initially, the lack of control and the loss of community felt overwhelming. At other times, it was the fairness and values mismatch of the social and political unrest that we were experiencing as a nation and that trickled into our work environments. Finally, as workload began to increase and restrictions continued to prevent a return to prepandemic practice, many of us started reconsidering the perceived rewards of practicing medicine at the vigorous pace we had kept before the COVID-19 lockdowns.

The pandemic refocused our intentions and reminded us that a slower pace and more intentional work-life balance can have a positive effect on our health and well-being. It’s not uncommon for our colleagues to say, “I don’t ever want to go back to seeing 50+ patients in a day,” or “I enjoyed spending more time and reconnecting with family and friends.” On the other hand, we miss the connections that in-person meetings bring. Virtual meetings allow us to stay connected and continue to learn, but human interactions are lacking.

CONCLUSION

A commitment to finding balance within our lives, gratitude for the advances of science and industry, and a renewed spirit of innovation are motivation to combat burnout. Going forward, we should all focus on the achievement of optimal health and understand that only when we are at our best can we be the best for our patients. Cheers to a brighter postpandemic world!

1. 2018 survey of America’s physicians: practice patterns and perspectives. Merritt Hawkins. September 2018. Accessed May 18, 2021. https://www.merritthawkins.com/news-and-insights/thought-leadership/survey/2018survey-of-americas-physicians-practice-patterns-and-perspectives

2. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PK, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281.

3. Rich A, Viney R, Needleman S, et al. ‘You can’t be a person and a doctor’: the work–life balance of doctors in training—a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e013897.

4. Wong AMF. Beyond burnout: looking deeply into physician distress. Can J Ophthalmol. 2020;55(3 suppl 1):7-16.

5. Saunders EG. 6 causes of burnout, and how to avoid them. Harvard Business Review. July 5, 2019. Accessed May 18, 2021. https://hbr.org/2019/07/6-causes-of-burnout-and-how-to-avoid-them