CASE PRESENTATION

A 75-year-old woman is referred by her glaucoma doctor for the surgical management of a dislocated IOL in the right eye. The patient has a history of pseudoexfoliation (PXF), and a trabeculectomy was performed on the right eye 6 years ago. She underwent bilateral cataract surgery 4 years ago with a plan for monovision, with the right eye focused for near.

On presentation, the patient describes intermittent blurring of her near vision that makes reading and working at a computer difficult. BCVA is 20/40 OD and 20/25 OS. IOP is 14 mm Hg OD and 16 mm Hg OS without medication.

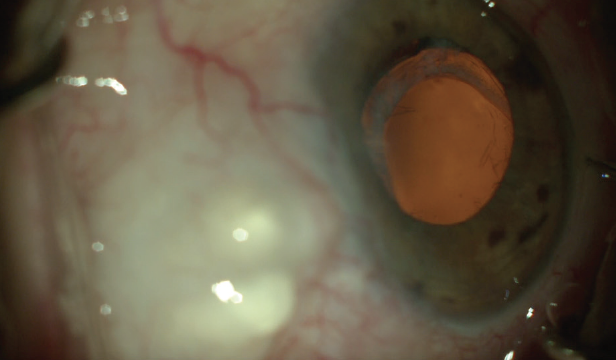

An examination of the right eye reveals an elevated avascular bleb superiorly, superficial punctate keratopathy, evidence of PXF debris at the pupillary margin, and a one-piece acrylic toric IOL in the bag that has dislocated inferiorly (Figure). Pseudophacodonesis is evident in both eyes but is much more significant in the right eye. The right eye has 1.50 D of corneal astigmatism at axis 002º.

Figure. The subluxated toric IOL.

The patient says that she has enjoyed her spectacle independence with monovision and would prefer to remain free of glasses if possible.

How would you proceed?

—Case prepared by Cathleen M. McCabe, MD

KENDALL E. DONALDSON, MD, MS

I find it interesting that BCVA is 20/40 when the IOL is minimally displaced. This raises concern about potential macular problems and ocular surface irregularities. The refraction and a macular OCT scan may reveal other irregularities and should be checked before surgical intervention.

PXF syndrome suggests that preexisting zonular weakness caused the lens to subluxate. When subluxation is mild, I sometimes elect to observe the patient for progressive vision loss. The presence of a one-piece IOL inclines me toward more conservative management here because most methods of alternative lens fixation work best with a three-piece lens. Another concern is that the lens implant is a toric model that is available only in one-piece designs. An IOL exchange for a fixated one-piece IOL will correct sphere only and leave preexisting astigmatism of approximately 1.50 D.

My preference would be an IOL exchange for a one-piece monofocal spherical IOL. Residual astigmatism can be corrected with LASIK or PRK approximately 3 months postoperatively, when the eye has healed and the refraction is stable.

I would start with a limited pars plana vitrectomy. This should allow me to safely elevate the IOL–capsular bag complex above the iris and bring both haptics into the anterior chamber while controlling vitreous prolapse, which could exert traction on the retina. A dispersive OVD would be injected behind the IOL–capsular bag complex, and Packer/Chang Cutters (MicroSurgical Technology [MST]) would be used to bisect the IOL; each half would be removed through a 2.5-mm temporal wound. After removal of the IOL–capsular bag complex, a small amount of preservative-free triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog, Bristol-Myers Squibb) would be instilled in the anterior chamber. If residual vitreous is identified, a vitrectomy would be performed through the original two vitrectomy ports 3.5 mm posterior to the limbus.

A CT Lucia 602 IOL (Carl Zeiss Meditec) would be fixated to the sclera using the Yamane technique, with lens power calculated as it would be for typical in-the-bag positioning. Before IOL implantation, the limbus would be marked with a radial keratotomy marker in two spots located 180º apart. The needle entry sites would be marked 2.5 mm posterior to the limbus, with two marks placed 2 mm apart for each needle pass. Two 30-gauge, 0.5-inch TSK needles would be bent to shorten their excursion into the vitreous space so that the bevel faces the haptic during docking. These needles may be placed on a 1-mL syringe to facilitate manipulation during docking of the haptics.

A CT Lucia IOL would be injected into the anterior chamber while the trailing haptic remains externalized until the leading haptic is secured in the 30-gauge needle. Next, 23-gauge microforceps (MST) would be used to assist with docking the leading haptic, which can then be externalized through the preplaced needle-syringe complex. Using 23-gauge microforceps (MST), the trailing haptic can then be docked into the second 30-gauge preplaced needle on a 1-mL syringe. Low-temperature cautery would then be applied to the haptics; the cautery tip would be held close to the haptics but would not touch them. Centration of the IOL can be adjusted by altering the length of haptic cauterized.

The globe can be stabilized throughout surgery by using the infusion from the vitrectomy. It may be helpful to maintain infusion until the end of the case. Alternatively, an anterior chamber maintainer may be used to avoid hypotony, which would make surgery much more difficult.

SOOSAN JACOB, MS, FRCS, DNB

I would refixate the dislocated IOL–capsular bag complex using a capsular fixation device. An Ahmed Capsular Tension Segment (Morcher) could be used, but my preference would be one of two techniques I have described, either the sutureless glued capsular hook technique1 (off-label) or a paper-clip capsule stabilizer (Morcher; see video below).

A peribulbar block would be administered, and gentle digital pressure would be applied to soften the eye to the desired extent. Use of a super pinky ball, a Honan balloon, or vigorous digital massage would be avoided to prevent possible damage to the thin avascular bleb, overfiltration, and chamber collapse. Because of ongoing zonulopathy that can occur in PXF, two lamellar scleral flaps would be created 180º apart in the horizontal meridian to fixate the bag on either side using an intrascleral haptic tuck technique for the capsular hook or paper-clip device.

The entire surgical procedure would be performed through sclerotomies and small paracentesis incisions to keep the corneal cuts away from the bleb area. Maintaining the physiologic plane of the capsular bag should allow the patient to retain the spectacle independence that she has enjoyed with monovision.

An anterior chamber maintainer would be fixated, and flow would be optimized to prevent chamber collapse while avoiding damage to the bleb. This should help to stabilize the anterior chamber. At the conclusion of surgery, all incisions would be sutured, and the conjunctiva and flap would be sealed with fibrin glue to prevent incisional leaks even in the event of postoperative hypotony from excess filtration through the bleb.

An NSAID such as bromfenac and dexamethasone would be prescribed postoperatively to blunt a potentially excessive inflammatory reaction secondary to PXF. The patient would be monitored for an IOP spike or bleb leak. Long-term follow-up is required to ensure glaucoma control. The bleb walls may thicken, constricting the bleb and decreasing filtration. Although these changes may reduce the superficial punctate keratopathy and dry eye or foreign body sensation that it may be causing, they may also compromise IOP control and necessitate additional medical or surgical management. Informed consent should include a discussion of the risks of surgery and postoperative complications.

Management of the left eye depends on the degree of pseudophacodonesis. If it is significant and there is a risk that the IOL–capsular bag complex may dislocate into the vitreous, a similar approach to what I have described may be used. Otherwise, close observation is advisable.

MARIA S. ROMERO, MD

When treatment options are discussed with this patient, consider the following issues:

- The relationship between the IOL–capsular bag complex and the pupillary area;

- Her age;

- The long-term viability of the implant;

- The integrity of the posterior and anterior capsules;

- Whether the bleb will interfere with any steps of the surgical procedure;

- Whether there are signs of inflammation; and

- The progressive nature of PXF.

If an examination confirms that the extent of zonular dehiscence is less than 3 clock hours, I recommend stabilizing the IOL–capsular bag complex by suturing it to the sclera with a lasso technique, such as one described by Dr. McCabe (see video below).

Two paracenteses would be created 180º apart, one in the area of zonular dehiscence. To prevent shallowing of the anterior chamber and to protect the bleb, a posterior chamber maintainer would be placed. The iris would be raised with a Sinskey hook in order to evaluate the eye for vitreous prolapse.

A capsular hook (MST) would be used to stabilize the IOL–capsular bag complex. Two marks would be made 3 and 4 mm posterior to the limbus in the sclera. A 25-gauge needle would be inserted at the posterior scleral mark, passed inferior to the haptic, and drawn through the capsular tissue.

Using 23-gauge microforceps, a No. 7 PTFE suture (Gore-Tex, W.L. Gore & Associates) would be inserted without the needle through the paracentesis opposite the area of zonular dehiscence and fed into the bore of the needle. This step would be repeated with the other arm of the suture engaged above the haptic and externalized through the superior mark on the sclera. Tension would be increased as needed to center the IOL, a slipknot would be tied, and the sutures would be buried.

The postoperative regimen would include a 6- to 8-week course of topical steroid therapy because patients with a history of trabeculectomy tend to have a heightened inflammatory response.

WHAT I DID: CATHLEEN M. MCCABE, MD

A dislocated IOL–capsular bag complex is always a challenge to manage. When it occurs in the setting of a functioning bleb, the challenge is amplified.

My goal here was to minimize the risk of a failed trabeculectomy while stabilizing the lens to maximize visual acuity. The patient had been functioning well with her toric IOL with monovision targeted for near, and her IOP was well-controlled. Possible solutions included an IOL exchange in which the one-piece acrylic IOL was replaced by either a three-piece IOL supported with a flange (Yamane technique), glued intrascleral haptic fixation, or iris sutures or possibly a sutured four-haptic lens (AO60, Bausch + Lomb). The astigmatism could be corrected with limbal relaxing incisions or subsequent PRK.

After discussing possible surgical techniques with the patient, we decided to proceed with a primary plan to retain the current IOL by fixating it in the appropriate axis (fortunately away from the axis of the bleb at 002º) using a belt loop technique with flanged sections of a 6-0 polypropylene (Prolene, Ethicon) suture looped around the haptic and anchored in the sclera. This strategy would preserve as much undisturbed conjunctiva as possible and, I hoped, avoid the need for an anterior vitrectomy. Backup plans included an IOL exchange with anterior vitrectomy followed by suturing a three-piece IOL (AcrySof MA60, Alcon) to the iris or externalizing the haptics for flange fixation to the sclera. Alternatively, an Akreos AO60 lens (Bausch + Lomb) was available for fixation to the sclera with a PTFE suture.

Belt loop four-flange fixation of a dislocated IOL–capsular bag complex begins with marking the conjunctiva 2 mm posterior to the limbus in two locations 180º apart—in this case at the 002º and 182º axis. A 30-gauge thin-walled TSK needle was bent at a 90º angle close to the hub with the bevel pointing up. This needle was passed through the conjunctiva and sclera 2 mm posterior to the limbus, under the haptic near the haptic-optic junction, through the capsular bag, and into the anterior chamber. A segment of 6-0 polypropylene suture cut at a bevel was then passed into the anterior chamber and threaded into the 30-gauge needle. The needle was withdrawn from the sclera, the suture was grasped and trimmed close to the sclera, and a flange was created with handheld cautery. (See video below.)

A second bent 30-gauge needle was passed 0.5 mm closer to the limbus at the same axis, this time passing through the sulcus in front of the capsular bag and haptic. The other end of the segment of 6-0 polypropylene was threaded into the needle and withdrawn through the sclera and conjunctiva to create a belt loop around the haptic. The 6-0 polypropylene suture was adjusted to remove slack, and a second flange was created with cautery.

Sometimes, only a single belt loop for one haptic is needed. In this case, a second belt loop was necessary to support the opposite side, and a similar procedure was performed for the temporal haptic at 182º. Final centration was adjusted by alternating tension on the belt loops and then creating new flanges when proper centration was achieved. It is important to create small flanges that are then pushed into the sclera to minimize the risk of future erosion through conjunctiva.

After removal of the OVD from the anterior chamber, the stability of the IOL was tested by moving the eye with 0.12-mm forceps. No vitreous presented in the anterior chamber, and a vitrectomy was not necessary. At the follow-up examination, the unmedicated IOP was 14 to 16 mm Hg, a functioning bleb was observed, and uncorrected near visual acuity was J1. The patient was pleased with the outcome.

It is beneficial for surgeons to have multiple strategies for fixating a dislocated IOL–capsular bag complex. In this challenging situation, particularly if a premium IOL is involved, it is desirable to avoid an IOL exchange and an anterior vitrectomy when possible. In eyes with a history of glaucoma surgery including tube shunt placement and trabeculectomy, use of the belt loop technique can allow the surgeon to avoid the bleb and preserve the conjunctiva.

1. Jacob S, Agarwal A, Agarwal A, Agarwal A, Narasimhan S, Ashok Kumar D. Glued capsular hook: technique for fibrin glue-assisted sutureless transscleral fixation of the capsular bag in subluxated cataracts and intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40(12):1958-1965.