I recently saw a 28-year-old man who had undergone CXL for keratoconus in May 2017 at a center in my area where epithelium-on (epi-on) CXL is performed with an unapproved riboflavin ophthalmic solution and device. His initial outcome was quite good: 5 months after CXL, his BCVA was 20/25-2 OU with newly fitted scleral contact lenses, and keratometry (K) was 50.00 D flat K/55.00 D steep K OD and 48.00 D flat K/52.30 D steep K OS.

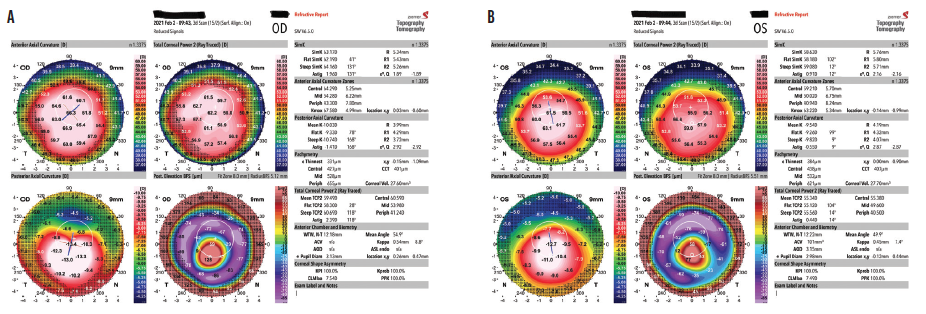

When I saw him in February 2021, however, his BCVA with a recent scleral fit was 20/80 OD and 20/70 OS. The referring optometrist had been managing the worsening vision with repeat scleral lens fittings until the strategy no longer seemed tenable. Imaging with the Galilei tomography system (Ziemer) showed diffuse inferior steepening in each eye—a classic picture of progressing keratoconus (Figure). Severe apical corneal thinning, worse in the right eye than the left, was observed, and early apical scarring and bilateral Fleischer rings were evident. K readings were now 62.10 D flat K/64.20 D steep K OD and 58.20 D flat K/59.10 D steep K OS.

Figure. Keratoconus progresses significantly during the 4 years following an unapproved epi-on CXL treatment. The tomography imaging shows diffuse inferior steepening in each eye and severe apical corneal thinning that is worse in the right eye (A) than in the left (B).

With 12.00 D of progression, I don’t believe additional CXL will be of much benefit in the right eye, so a deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty has been scheduled. I suspect that the left eye may require a corneal transplant in the future. I, however, am planning first to perform epithelium-off (epi-off) CXL using the FDA-approved iLink (Glaukos) to slow or halt keratoconus progression and improve the patient’s ability to be fit for and see well with a scleral lens. Unfortunately, he has lost vision that he will never regain and now faces multiple surgical procedures, long recovery periods, and complex long-term management. (Editors’ note: See the accompanying sidebar for details on a genetic test that can facilitate early and accurate decision-making when managing patients with keratoconus.)

Quantifying the Risk and Presence of Keratoconus and Other Corneal Genetic Disorders

By Vance Thompson, MD, FACS

With all the technologies that help ophthalmologists to provide better treatment and outcomes for patients, one frontier of eye care that has yet to be fully realized is genetics. Other medical disciplines such as oncology have greatly benefited from what the scientific community has learned about the genome. On the other hand, the full scope of how genetics can aid the ophthalmic community is not yet apparent, but the picture is becoming clearer.

A PERSONALIZED GENETIC EYE TEST

The AvaGen (Avellino) genetic test provides personalized genetic data to accurately quantify an individual’s genetic risk of keratoconus and the presence of transforming growth factor beta–induced corneal dystrophies (data on file with Avellino).

The test is simple to perform with a noninvasive buccal swab. Reviewing the results helps me to determine if a patient with suspicious topography or other red flags is a candidate for LASIK, PRK, or a phakic IOL. The test also helps to identify individuals with a high genetic risk for keratoconus who may be candidates for CXL or another treatment to slow disease progression.

Genetic testing can supplement traditional ocular imaging in patients with other suspicious findings. The additional data can help guide surgical decision-making and improve surgical outcomes. If keratoconus is detected by the test, I encourage patients to consider having their children and/or siblings get tested. This expanded testing helps to identify patients at genetic risk for keratoconus earlier, which can allow sight-saving interventions to be performed sooner and thus protect vision.

CONCLUSION

I anticipate that technological advances will enable ophthalmologists to identify and treat patients with keratoconus earlier than is currently possible, and I look forward to seeing other areas where genetics can be applied in ophthalmology. In my opinion, the incorporation of genetics into ophthalmology is something to be welcomed.

In my opinion, there are at least five unfortunate elements to this case.

An Unapproved Procedure and Drug

This patient underwent CXL with drug and device products that have not gone through the FDA approval process. Some published data on alternative CXL protocols notwithstanding, no randomized controlled trial data are available that provide strong evidence that this drug-device combination works as well as the FDA-approved system. Nor is there FDA oversight to ensure that appropriate manufacturing quality control systems are in place for the products.

Epi-on CXL

The patient underwent an epi-on procedure. Epi-on CXL is appealing because it is faster to perform, may cause the patient less discomfort, and theoretically reduces the risk of complications associated with epithelial removal. However, in most studies, the results of current epi-on protocols are inferior to those achieved with the epi-off or Dresden protocol that is approved in the United States.1-3 Stability has been reported for up to a decade after epi-off CXL.4-7 A small percentage of eyes experience disease progression after epi-off CXL, so it is impossible to know if this patient’s keratoconus would have progressed after epi-off CXL as well. Still, when a procedure performed with unapproved products is ineffective, both the doctor who performed the procedure and the referring doctor are in a much more precarious medicolegal position than they would be in the rare instance when a procedure that is the standard of care fails.

High Expense

Because he underwent an unapproved CXL procedure, the patient paid thousands of dollars out of pocket when he could have undergone an FDA-approved procedure that is well covered by commercial insurance. He viewed the money spent as worthwhile because it could allow him to avoid a corneal transplant, but now he needs a transplant.

The Patient Was Poorly Informed

The patient was poorly informed about his options and prognosis. Neither the original referring optometrist nor the surgeon who performed CXL informed the patient that an FDA-approved procedure was available. Additionally—and this could certainly have been a misunderstanding on the patient’s part—he believed there was no chance of disease progression postoperatively.

Prolonged Postoperative Progression

Keratoconus continued to progress for 3 years after CXL. The patient’s vision was being managed with scleral lenses, but the optometrist could have referred the patient for retreatment earlier when more of his visual acuity might have been preserved.

Conclusion

I hope someday patients can undergo a validated epi-on CXL procedure with an approved drug and device, but clear evidence of safety and efficacy from randomized controlled clinical trials is required. Until then, I think it is best to offer patients only the FDA-approved CXL procedure because it was proven safe and effective through rigorous clinical trials, it can slow or halt the progression of keratoconus, and it is well covered by insurance.

Of course, the risks and benefits of CXL must be considered for each individual. Additionally, patients with keratoconus should be observed after CXL for signs of disease progression that may warrant further intervention.

1. Rush SW, Rush RB. Epithelium-off versus transepithelial corneal collagen crosslinking for progressive corneal ectasia: a randomised and controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(4):503-508.

2. Choi M, Kim J, Kim EK, et al. Comparison of the conventional Dresden protocol and accelerated protocol with higher ultraviolet intensity in corneal collagen CXL for keratoconus. Cornea. 2017;36(5):523-529.

3. Kobashi H, Rong SS, Ciolino JB. Transepithelial versus epithelium-off corneal crosslinking for corneal ectasia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(12):1507-1516.

4. Poli M, Lefevre A, Auxenfans C, Burillon C. Corneal collagen CXLfor the treatment of progressive corneal ectasia: 6-year prospective outcome in a French population. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(4):654-662.

5. O’Brart DP, Patel P, Lascaratos G, et al. Corneal CXL to halt the progression of keratoconus and corneal ectasia: seven-year follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(6):1154-1163.

6. Raiskup F, Theuring A, Pillunat LE, Spoerl E. Corneal collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A light in progressive keratoconus: ten-year results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(1):41-46.

7. Vinciguerra R, Pagano L, Borgia A, et al. Corneal CXL for progressive keratoconus: up to 13 years of follow-up. J Refract Surg. 2020;36(12):838-843.