The Economics of Transitional Pass-Through Status

By Kirk A. Mack, COE, COMT, CPC, CPMA

What is pass-through status? What does it do? How is it used? There is a lot of confusion among ophthalmologists about pass-through status.

Let’s make it simple: Think of pass-through status as an opportunity for ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) and the outpatient departments of hospitals to use a new product without financial risk. The pass-through payment for the new product is in addition to Medicare’s standard reimbursement. This discrete payment is a way for CMS to encourage the use of innovative technologies by supporting doctors or facilities trying something new.

Ophthalmologists and facilities that take advantage of this opportunity can:

- Use the new drugs and devices that have pass-through status without incurring an economic penalty or risk;

- Evaluate whether they think the new technology conveys a benefit; and

- Ultimately decide whether to incorporate the new product permanently into their routines.

There are currently several innovative ophthalmology products with transitional pass-through status from CMS. This is notable, as there are generally only a few dozen products with this status at a given time in all of medicine.1 Due to confusion about the nature of pass-through status, some practitioners may be wondering how to take advantage of it. This article is meant to help clear up some of that confusion.

TRANSITIONAL STATUS

First, consider the terminology. You may hear about pass-through billing, which occurs when a physician or facility requests and bills for a service, but the service is performed by another entity.2 For example, pass-through billing occurs when a provider (eg, physician or hospital) pays a laboratory to perform its tests and then files the claims as though it had performed them. That approach is separate and distinct from the temporary transitional pass-through status, which is what we are discussing.

CMS gives drugs with transitional pass-through status a 2- to 3-year window during which they receive separate payment.3 For new pharmaceuticals with transitional pass-through status, Medicare pays the drug’s wholesale acquisition cost plus 6% for the first 2 quarters and then the average sale price plus 6% for the remainder of the pass-through period. The CMS website publishes quarterly updates of the national rates for pass-through pharmaceuticals.1

The designation of transitional status is meant to provide a bridge to the regular payment structure while the new product becomes better established in the market. Each year, CMS estimates the total amount it expects to pay for all transitional pass-through products and allocates a pool of money specific to that purpose. There is no limit on utilization of the pass-through products.

Without the separate payment, it’s possible that these novel drugs or devices might be cost-prohibitive and never have the chance to establish a market, even though they may be beneficial for patients. Pass-through status gives these products breathing room to build an audience of users.

IN OPHTHALMOLOGY

There are currently three drug products with pass-through status in our field. All, for the most part, are linked to cataract surgery.

Dexamethasone intraocular suspension 9% (Dexycu, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals). A sustained-release formulation of the steroid, Dexycu is indicated for the treatment of postoperative inflammation. It is delivered at the end of surgery as a sphere of drug using the Verisome technology. This product has pass-through status through September 2021 (HCPCS code: J1095).

Dexamethasone ophthalmic insert 0.4 mg (Dextenza, Ocular Therapeutix). Another sustained-release formulation of the steroid, Dextenza is indicated for the treatment of inflammation and pain after ophthalmic surgery. This intracanalicular insert is placed in the punctum and into the canaliculus to deliver drug to the ocular surface. It has pass-through status through June 2022 (HCPCS code: J1096).

Phenylephrine and ketorolac intraocular solution 1%/0.3% (Omidria, Omeros). Added to the irrigating solution during cataract surgery, Omidria is indicated for maintaining pupil size by preventing intraoperative miosis and for reducing postoperative ocular pain. CMS granted pass-through status from 2015 to 2017, and then issued a 1-year extension of pass-through status for this product in October 2019, good through October 2020 (HCPCS code: J1097).

BENEFITS OF USE

Aside from the financials (average sale price plus 6%), pass-through products usually offer clinical benefits for surgeons and patients.

In the case of Omidria, the drug has been shown to reduce the risk of intraoperative complications from intraoperative floppy iris syndrome in patients taking alpha-1 blockers and postoperative complications.4,5 (Editor’s note: For more on Omidria, see “Update on Drug Delivery Techniques,” pg 46.)

Regarding the two extended-release steroids, both can simplify and streamline postoperative care by reducing patients’ medication regimens. This may allow surgeons to reduce the number or extent of follow-up visits needed. In this time of lockdowns and telemedicine, fewer in-person visits may be a definite advantage.

REIMBURSEMENT

Typically, the facility, whether hospital outpatient department or ASC, completes the paperwork for drugs with transitional pass-through status. Because these products are used during surgery, the facility, not the surgeon’s practice, orders and stocks them.

To seek reimbursement from the payer, which in this case is Medicare, the facility adds a line item with the appropriate supply code (ie, National Drug Code number), and indicates the amount and the number of units to the claim submitted to CMS.

Once you know which items have pass-through status, the Medicare reimbursement process is relatively straightforward. Note that it may get tricky if a physician uses one of these products on a non-Medicare patient. Commercial payers are not obligated to offer separate additional reimbursement for the drug. Also, they may not allow the cost to be passed on to the patient. Over time, however, commercial payers have been known to follow the CMS guidelines. It is always best to check with the payer before you use a pass-through drug on a non-Medicare patient.

CONCLUSION

Transitional pass-through status allows physicians to try a novel product without economic risk. It’s a chance to try something new that might otherwise not make it to the marketplace. In this way, pass-through can be helpful to both surgeons and industry, giving surgeons the opportunity to provide better care for their patients and industry the support it might need to reach a larger audience of users.

1. Gustafson TA. Transitional pass-through payments. ASC Focus. September 2015. Reprinted on Omidria website. http://www.omidria.com/wp-content/uploads/ASC-Focus-Reprint-Sept2015-Gustafson.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020.

2. Pass-through billing. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas. https://www.bcbstx.com/provider/claims/pass_through_billing.html. Accessed June 16, 2020.

3. Social Security Administration. Social Security Act §1833(t)(6)(C) https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1833.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

4. Silverstein SM, Rana VK, Stephens R, et al. Effect of phenylephrine 1.0%-ketorolac 0.3% injection on tamsulosin-associated intraoperative floppy-iris syndrome [published correction appears in J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(12):1537]. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(9):1103-1108.

5. Rosenberg ED, Nattis AS, Alevi D, et al. Visual outcomes, efficacy, and surgical complications associated with intracameral phenylephrine 1.0%/ketorolac 0.3% administered during cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;12:21-28.

Compounded Therapeutics: Seven Situations When a Closer Look at Compounding Pharmacy Options is Warranted

By William F. Wiley, MD

Surgeons should consider the use of compounded medications in addition to branded and generic pharmaceuticals from traditional sources. Compounded medications may present advantages in convenience, cost, and/or patient compliance in certain instances.

This article presents seven situations in which I believe clinicians should consider use of a compounded medication.

Situation No. 1: To improve compliance with combination drops. In my practice, I have replaced multibottle regimens with compounded combination drops whenever possible. In most cases, we can deliver these medications at the point of service, so I don’t have to worry that patients haven’t filled their prescription or that the pharmacy has substituted a different drug from its formulary. More important, a combination drop in a single bottle eliminates confusion about which drop to use when.

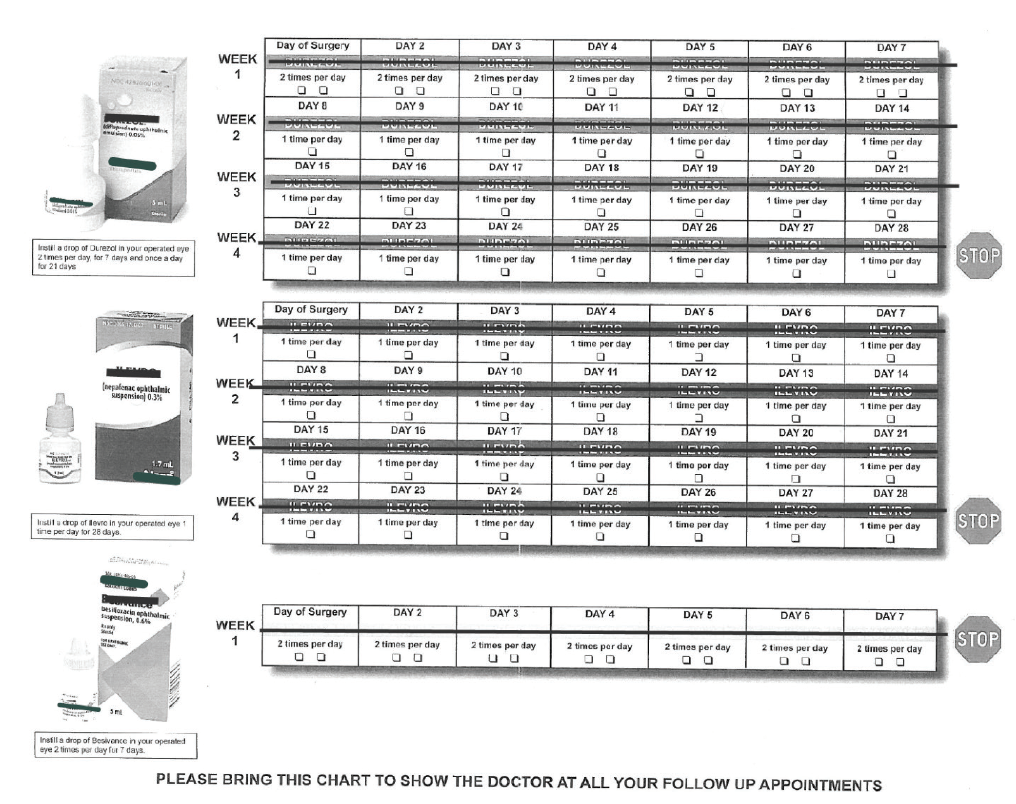

In the past, my typical postcataract regimen involved three bottles, each with a different daily schedule and duration (Figure). This was hard for patients to follow as intended, especially those with any cognitive or dexterity challenges. One study showed that 31% of patients undergoing cataract surgery had difficulty instilling drops and 92% used improper technique.1 With a combination drop, I’m much more confident that patients will be compliant with the regimen I want them to have after surgery.

Figure. Before using compounded pharmaceuticals, Dr. Wiley’s typical postcataract regimen involved three bottles, each with a different daily schedule and duration.

Today, I give most cataract patients a sub-Tenon triamcinolone/moxifloxacin injection at the end of surgery and prescribe a topical triple drop of prednisolone, moxifloxacin, and nepafenac (Pred-Moxi-Nepaf, ImprimisRx) q.d. for 4 weeks. With this approach, in an analysis of more than 400 eyes, I have had no occurrences of endophthalmitis or breakthrough inflammation, a 0.25% rate of cystoid macular edema, and no IOP spikes.

Adherence to a drop schedule is even worse among patients with chronic conditions. In one study, about 45% of glaucoma patients who had undergone cataract surgery were less than 75% compliant, even under the best of circumstances.2 As soon as a second drop is added, compliance further declines and refill intervals lengthen.3 To mitigate these challenges, combinations of glaucoma medications can be compounded, including triple and quadruple drops that aren’t available from any commercial source.

Situation No. 2: When there is a drug shortage. The law governing compounding pharmacies, the Drug Quality and Security Act, expressly mentions the need to fill drug shortages as one reason for the existence of these companies. Because compounding pharmacies can buy ingredients in bulk and make eye drops, pills, and other forms of medication, they are often able to supply a drug that is temporarily unavailable from one’s usual source. Drug shortages are especially common with old, low-cost medications for which manufacturers have little incentive to increase production.

Situation No. 3: To keep costs low. The cost of medications is important to patients, and they may be more likely to adhere to a regimen when the cost is lower.4 Generic formulations of ophthalmic drugs are typically more affordable than branded drugs, but there has been debate over whether they always offer the same efficacy and safety. Studies have shown that generic drops have more variation in their active ingredients, undergo changes in the active ingredient with heat exposure, and contain more particulate matter compared with branded drugs.5

In general, I prefer compounded medications over generic drugs. I know the compounded medications I buy from a 503B pharmacy (see Choose Your Compounding Sources Wisely) are made in US facilities with the same oversight and inspection as major pharmaceutical companies. Additionally, compounding combines multiple drugs in a single bottle, which is more cost-effective for the patient.

CHOOSE YOUR COMPOUNDING SOURCES WISELY

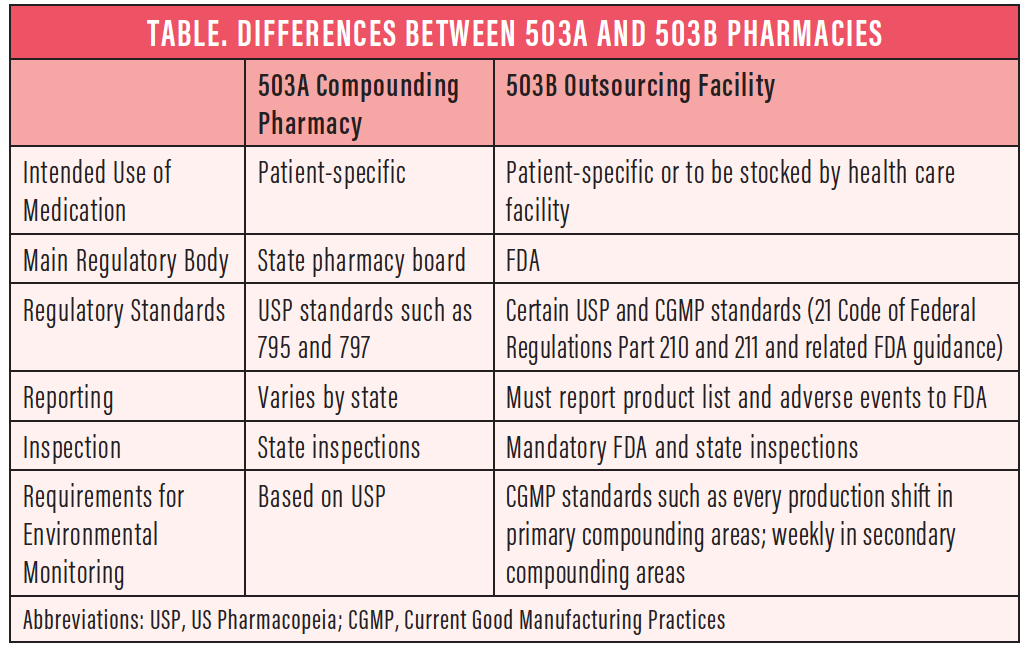

Under the Drug Quality and Security Act, pharmacies may be regulated in two different ways, under either Section 503A or Section 503B of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (Table).

503A compounding pharmacies. These are similar to traditional compounding pharmacies. They remain primarily state-regulated and can make formulations only for an individual patient prescription.

503B outsourcing facilities. These are mainly FDA-regulated outsourcing facilities that must follow Current Good Manufacturing Practices requirements. They are subject to the same FDA inspection and oversight as large pharmaceutical companies. 503B pharmacies can make formulations to meet the needs of a clinic, hospital, or ambulatory surgery center and provide them directly to the facilities and providers.

Situation No. 4: When you need something unique. If I have a patient with a rare infection that is resistant to traditional antibiotics, for example, I will order a compounded fortified antibiotic, most likely from a local compounding pharmacy. Or, if a patient is allergic to a particular preservative or ingredient, a compounding pharmacy can make a medication without the offending ingredient specifically for that patient.

Situation No. 5: To improve patient comfort. For nearly all my cataract surgery cases, I now use a compounded sublingual sedative tablet containing midazolam 3 mg, ketamine HCl 25 mg, and ondansetron 2 mg (MKO Melt, ImprimisRx). Several ophthalmic colleagues and I, along with anesthesia providers, developed this medication for conscious sedation during cataract surgery. It dissolves in about 2 minutes and reaches peak effect about 15 minutes later. In our practice, this has helped to reduce patient anxiety and has nearly eliminated the need for intravenous sedation, reducing staff time and ASC costs. Compounding pharmacies also offer topical or injectable anesthetic and pain-relief medications for ophthalmic surgery.

Situation No. 6: To limit preservative exposure. Chronic exposure to benzalkonium chloride and other preservatives is harmful to the ocular surface.6 In addition to branded preservative-free formulations, compounded medications are helpful if I can’t obtain a preservative-free drop, especially for patients with chronic conditions such as dry eye or glaucoma. Approximately half of glaucoma patients have abnormal Ocular Surface Disease Index scores,7 and 60% of them report dry eye symptoms.8 Anything we can do to reduce the cumulative toxicity of preservatives is helpful.

Situation No. 7: When you need a smaller dose. Self-compounding in the ASC is increasingly frowned upon, as is adding multidose medications to the irrigating solution or using them for multiple patients. A compounding pharmacy can provide single-use packaging of medications for a wide range of ophthalmic needs, including maintenance of pupil size during surgery to treatment of macular degeneration.

CONCLUSION

Compounded medications have important roles to play in contemporary ophthalmic surgery. For physicians they offer greater choice, for patients they offer good value, and for both parties they offer the benefits of improved compliance.

1. An JA, Kasner O, Samek DA, Lévesque V. Evaluation of eyedrop administration by inexperienced patients after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40:1857-1861.

2. Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, et al. Adherence with topical glaucoma medication monitored electronically. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(2):191-199.

3. Robin AL, Covert D. Does adjunctive glaucoma therapy affect adherence to the initial primary therapy? Ophthalmology. 2005;112(5):863-868.

4. Stein JD, Shekhawat N, Talwar N, Balkrishnan R. Impact of the introduction of generic latanoprost on glaucoma medication adherence. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(4):738-747.

5. Kahook MY, Fechtner RD, Katz LJ, et al. A comparison of active ingredients and preservatives between brand name and generic topical glaucoma medications using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37(2):101-108.

6. Baudouin C, Labbé A, Liang H, et al. Preservatives in eyedrops: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(4):312-334.

7. Fechtner RD, Godfrey DG, Budenz D, et al. Prevalence of ocular surface complaints in patients with glaucoma using topical intraocular pressure-lowering medications. Cornea. 2010;29(6):618-621.

8. Leung EW, Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Prevalence of ocular surface disease in glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(5):350-355.