Richard Lindstrom, MD, did not choose medicine; it chose him, he explains. What an excellent choice it was. He launched a practice that has grown to five locations with 300 employees and helped develop the most popular corneal preservation medium in the world. Now, he is helping the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) prepare astronauts for Mars. Dr. Lindstrom is this month’s Living Legend.

How did you decide to become an ophthalmologist?

I went to college to train to join Lindstrom Restoration, the family construction business that my father founded in 1945 after World War II. I was a good student and in the honors division, and by serendipity, I ended up with the dean of the medical school as my advisor. It took him about a year to talk me into going to medical school, and according to him, it had to be at the University of Minnesota. Unlike most students, medicine chose me instead of my choosing medicine.

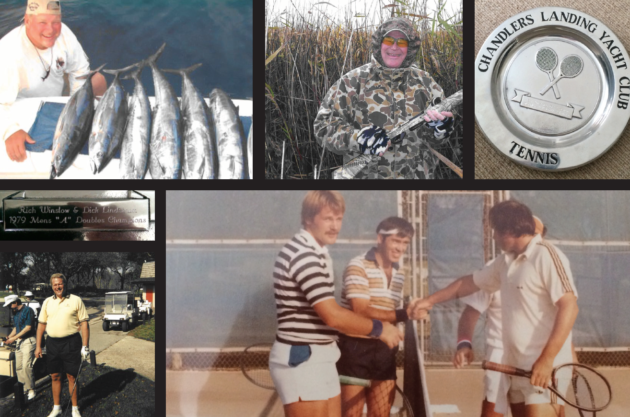

Clockwise: fishing in Panama; hunting in Canada; the Chandlers Landing Tennis Championship trophy; Dr. Lindstrom (left) and tennis partner Richard Winslow, MD (second from left), after the win; golfing at a Royal Hawaiian Eye meeting with Jack Holladay, MD.

The same thing happened to me in medical school. A young, dynamic, new assistant professor, Donald J. Doughman, MD, joined the ophthalmology faculty after a 2-year fellowship in cornea at Harvard. He needed a medical student to help him with some research in corneal preservation. Through the same dean, Dr. Doughman found me. After 2 years in the lab with him, I was on my way to a residency and fellowship in cornea. Again, it had to be at the University of Minnesota, which allowed me to continue my research and eventually produced Optisol GS (Bausch + Lomb), the most popular corneal preservation medium in the world.

What kind of work do you do with NASA?

Nearly all male NASA astronauts develop visual impairment and intracranial pressure (VIIP syndrome) after 3 months in space, where body fluids tend to shift cephalad because there is no gravity. VIIP syndrome appears to be less frequent in female astronauts. Those affected develop choroidal swelling with choroidal folds, secondary hyperopic shift, and disc edema. In some cases, there have been flame hemorrhages. Although no one has suffered permanent vision loss, the hyperopic shift is permanent.

From left: Dr. Lindstrom, Dr. Winslow, and their opponents after the match.

NASA wants to send astronauts to Mars in the next decade, which would be a 500- to 600-day trip. If VIIP syndrome cannot be solved or at least mitigated, the risk of blindness could make such a trip impossible. The challenge to diagnose, manage, and potentially prevent or at least treat this problem prompted NASA to put together a blue-ribbon panel for a project coined “Vison for Mars.” I was honored to be invited to join the group. We have met several times, and four interesting research projects, including diagnostic and therapeutic technologies, have received research funding.

Of what accomplishment are you most proud?

I have two children who are happily married and living near me with their five healthy children: two boys and three girls between the ages of 3 and 8. I have a wonderful marriage to a great woman, Jaci Lindstrom. These are the most important accomplishments of my life, and I continue to work on and nurture my family every day.

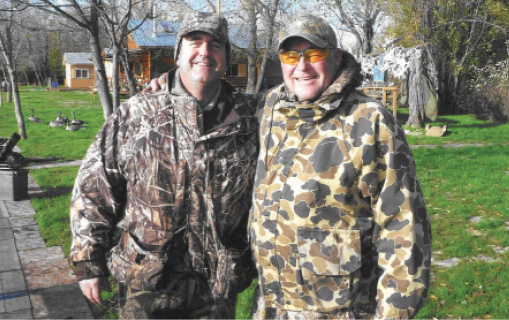

Vance Thompson, MD, and Dr. Lindstrom set out on a hunting trip in Niska, Canada.

I have published nearly 400 peer-reviewed publications, edited numerous books, and invented several products that are widely used in ophthalmology. I have traveled the world sharing ideas and educating my colleagues. For more than 20 years, I have served as the global medical editor of Ocular Surgery News. I enjoyed 10 years in full-time academics. I rose to full professor and held the Harold G. Scheie research chair in ophthalmology when I decided to transition to private practice. In 27 years, my colleagues and I have grown Minnesota Eye Consultants from one doctor—me—and one office with six employees to 26 doctors, five offices, and 300 employees. All of this is worth noting, but what I am more proud of are the 80 fellows I have trained over the past 40 years in ophthalmology. These very special colleagues and friends have made tremendous contributions to ophthalmology around the world. Their achievements give me great joy.